Side Gallery

Side Gallery

WishlistFollow

MODERNO: DESIGN FOR LIVING IN BRAZIL, MEXICO AND VENEZUELA, 1940-1978

NEW YORK CITY

AMERICAS SOCIETY

FEB 11 1994 - MAY 16 2015

Moderno: Design for Living in Brazil, Mexico, and Venezuela, 1940–1978 explored how design, one of the most ground-breaking chapters in the history of Latin American modernism, transformed the domestic landscape in a period marked by major stylistic developments and social political changes. Away from the mass destruction of World War II, many Latin American countries (specifically Brazil, Mexico, and Venezuela) entered a period of economic growth in the late 1940s and through the 1950s, which resulted in the modernization of major cities.

Although each country had unique cultural and historic values, modern ideals were enthusiastically embraced as a vehicle for progress. The slogan “fifty years of progress in five,” used in the 1950s by President Juscelino Kubitschek, best described Brazil’s national agenda for fast economic growth and illustrated the urgency of change across the region. Modernism was officially embraced as the suitable style for these nations and design was endorsed as a vehicle for development. By encouraging “a modern way of living” as an ideology, the governments promoted adoption of their modernization goals.

"Moderno as an exhibition strove to reposition modern Latin American design within a larger global context to explore how an influx of European and North American architects, designers and entrepreneurs helped expand the field of design by fostering a cosmopolitan and creative environment"

The post-World War II era steered a period of artistic vivacity in Latin America. As national art scenes flourished, new design dialogues were invented, and architects and designers began to see themselves as active players in the creation of modern national identities. With private and public support, Latin American designers developed their particular styles that reflected both the changing cultural climate and local material traditions. The administrations promoted national industries, particularly those that supplied a growing demand for consumer goods for the home. This renewed utopian hope encouraged designers and studio-craft artists to produce modern pieces that were specifically adapted to local tastes, as well as environmental climates.

Moderno as an exhibition strove to reposition modern Latin American design within a larger global context to explore how an influx of European and North American architects, designers and entrepreneurs helped expand the field of design by fostering a cosmopolitan and creative environment. The Bauhaus and other European vanguard groups were also influential to designers who assimilated these ideologies into innovative designs they produced for their regional publics. In addition, the groundbreaking international design competition “Organic Design in Home Furnishings” organized in 1940 by the Museum of Modern Art, featured a section devoted to Latin American design and played a significant role in the international dissemination of these designers’ works.

More info at https://www.as-coa.org/moderno-design-living-brazil-mexico-and-venezuela-1940-1978

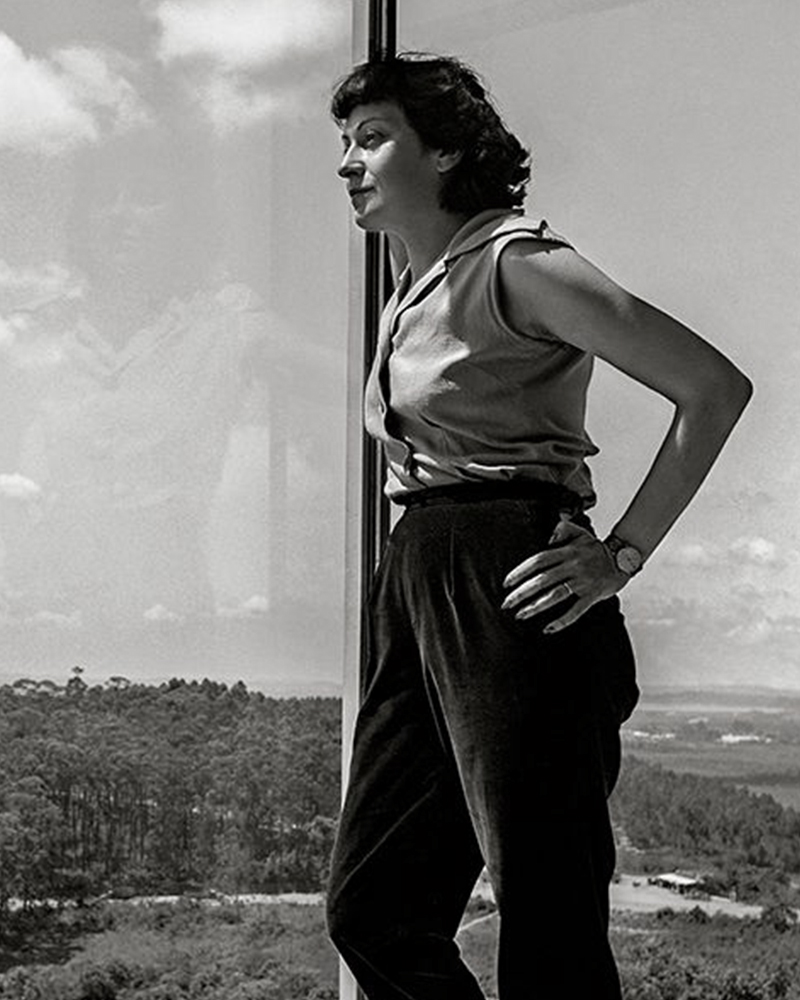

Achillina Bo, best know as Lina Bo Bardi, (born December 5, 1914, Rome, Italy—died March 29, 1992, São Paulo, Brazil), was an Italian-born Brazilian Modernist architect, industrial designer, historic preservationist, journalist, and activist whose work broke free from convention. She designed daring, distinctive structures that merged Modernism with populism.

Bo Bardi graduated with an architecture degree in 1939 at the University of Rome, where she had studied under architects such as Marcello Piacentini and Gustavo Giovannoni. Upon graduating, Bo Bardi moved to Milan and began working with the architect Carlo Pagani as a design journalist. She also worked with the famous architect and designer Gio Ponti and collaborated with him on the magazine Lo Stile, while contributing to several other Italian design publications. In 1944 she became deputy director of Domus, the acclaimed design magazine established by Gio Ponti in 1928, and retained the post until 1945. In 1945 Domus commissioned Bo Bardi, Pagani, and photographer Federico Patellani to travel through Italy documenting the destruction of World War II. Later that year, she collaborated with Pagani and art critic Bruno Zevi on the short-lived magazine A – Attualità, Architettura, Abitazione, Arte, which published their judgments and verdicts discussed ideas for restoration of the postwar devastation.

Pietro Maria Bardi, an art gallery director, dealer, and critic, became her husband in 1946. Pietro was soon invited to Brazil by the media tycoon Assis Chateaubriand to help coordinate the Art Museum of São Paulo (Museu de Arte de São Paulo; MASP). The couple, as a result, emigrated across the Atlantic to the modernist hotspot Sao Paulo.

Bo Bardi designed the interior and the museum fittings for the first iteration of MASP, which opened in 1947. She developed an innovative system for suspending paintings away from the wall. (Her design was torn down in the 1990s and replaced with a conventional wall hanging system.) She also designed folding stackable chairs made from Brazilian jacaranda wood and leather intended for use at lectures and museum events. Later in life, she curated an exhibition at the museum on the history of chair design.

In 1950 Bo Bardi founded the magazine Habitat with her husband and worked as the editor until 1953. During that time, it was the most influential architectural magazine in Brazil. She became a citizen of Brazil (1951) and started the country's first industrial design course at the Institute of Contemporary Art (a part of the expanded MASP). She designed for her and her husband, the notorious Modernist Le Corbusier, influenced Casa de Vidro (Glass House) in the Morumbi neighborhood of São Paulo. Constructed on a hill, Casa de Vidro, over time, integrated into the landscape entirely. The front of the house extended out over the slope of the hill, elevated and supported on delicate-looking stilts. In 1951 she also designed her most famous piece of furniture, Bardi's Bowl, a chair in the form of an adjustable hemispherical bowl resting in a steel cradle.

By the mid-1950s, it was clear that MASP had outgrown its original building, with galleries and dedicated spaces for teaching art. By the 1950s, the popularity of MASP overcame the museum's physical capacity. In 1958 Bo Bardi was commissioned to design the new building. The building stands today as her most dominant creation. Located on São Paulo's Paulista Avenue, Bo Bardi's iconic glass-and-concrete building was elevated 8 meters (26.2 feet) above the ground on sizeable red pillars. The space at ground level provides a shaded heaven away from the hot summer sun and a gathering place for concerts, protests, and socializing.

In the late 1950s Bo Bardi began an extended period of living and working in Salvador, a poor city rich in cultural heritage in the northeastern state of Bahia. She gave several lectures at Bahia University's School of Fine Arts in 1958, and in 1959 she was invited to create and run Bahia's Museum of Modern Art (Museu de Arte Moderna da Bahia). She chose to house the museum in the Solar do Unhão, a former salt mill and part of a network of historic seaside constructions that she restored in 1963. Bo Bardi added a museum of popular art and an art school to the Museum of Modern Art, all under the roof of Unhão.

However, political unrest forced Bo Bardi to leave Bahia in 1964. Her return to São Paulo marked the beginning of Brazil's lengthy era of oppression under a military dictatorship that lasted until 1985. During that period, Bo Bardi curated exhibitions and worked in theatre, designing sets and costumes for several productions, notably a 1969 production of Im Dickicht der Städte (In the Jungle of Cities), an early play by Bertolt Brecht.

Bo Bardi's time in Bahia altered her political and aesthetic philosophies. The region's language and historic architecture led her to adopt a design process guided by social and ethical responsibility and inspired by allegiance to her adopted country and its native aesthetic traditions. Bo Bardi dedicated herself to creating only Brazilian architecture, projecting simple designs, and sourcing local materials, the style of architecture she called "Arquitetura Povera" ("poor", or, "simple" architecture). Since her initial experience in Salvador, much of her work involved re-designing and developing existing structures and restoring and preserving historic buildings. Throughout the 1980s Bo Bardi led preservation and restoration projects in the historic center of Salvador, including the House of Benin, which houses an art collection, as well as Misericórdia Hill, an extremely steep historic street (both in 1987). Her next major architecture project was the SESC Pompéia (built in stages, 1977–1986), a leisure and cultural center in São Paulo sponsored by the nonprofit Social Service of Commerce (Serviço Social do Comércio). Bo Bardi converted an old steel drum factory into a center for various facilities; sports, theatre, and other leisure activities.

Bo Bardi, although late, has been given her due as one of the most prolific women architects of the 20th century. In the mid-1980s, working alongside the architects André Vainer and Marcelo Carvalho Ferraz, Bo Bardi designed an addition to the Glass House, the Instituto Lina Bo e P.M Bardi (originally the Instituo Quadrante). As well as housing Bo Bardi's archive, The Instituto Lina Bo e P.M Bardi is an exhibition space dedicated to the study of Brazilian art and architecture.

In 2012, the centennial of her birth, Bo Bardi's career was celebrated with the launch of a limited-edition line of her bowl chair, a major traveling retrospective organized by the British Council in London, and the publication of a scholarly monograph discloses her life's work.

Cornelis Zitman was born in 1926 into a family of builders. At the age of 15, he started studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in The Hague. His studies terminated in 1947; he then refused to enroll in the required military service objecting to the Dutch political activities in Indonesia and thus left the country aboard a Swedish oil tanker that would take him to Venezuela.

He settled in the city of Coro, where he found employment as a technical draftsman in a construction company. He began to paint in his free time and make his first forays into the field of sculpture. Two years later, he moved to Caracas, where he worked as a furniture designer for a factory of which he would later become the director. In the early 1950s, Zitman, in partnership with the engineer Antonio Carbonell went on to create Tecoteca, his furniture manufacturing company. The exceptional curation of what Cornelis J. Zitman produced in the years he designed and manufactured furniture offered an insight into the manufacturing of modern furniture in Venezuela, which is still very much being discovered and rests on the shelf of the things that hope to be better understood and settled in the country's recent history. There is nothing but tremendous praise for the designer; his work is now reconnecting with the public, the audience for whom it was originally designed.

The life of Tecoteca itself was relatively short-lived, not due to the shortcomings of the furniture but to a series of unfortunate events and the social and political situation. Four years after its creation, Tecoteca went from one crisis to another. In 1956, his workshop in Boleíta caught fire. Although the project for its reconstruction and relaunch in Cagua had been programmed and carefully studied with the acquisition of machinery and the establishment of procedures of the latest technological ability, the business bankruptcy occurred admits a tidal wave of the economic and political changes in 1958, which proved unpredictable and unrecoverable. The name Tecoteca was liquidated along with its assets and acquired as a brand for the production of kitchen furniture. Today it survives as the name of a building located on Avenida Francisco de Miranda, south of the Atlantic building, in Los Palos Grandes, near where in its heyday Tecoteca had its most impressive store.

A mixture of admiration and disbelief is the feeling that best accompanies the life of Tecoteca. It was an era of splendor and misery. The portfolio of forms and functions furnished the Monserrat residential building in Altamira, the work of Emile Vestuti when he worked at the firm of architects Guinand and Benacerraf, and the renowned Club Táchira de Fruto Vivas, through a concerted program, focused on the production of standardized furniture for oil camps for Shell company in Venezuela, which Zitman conceived with managerial logic and quality.

Good quality and economical furniture was what Zitman had became known for, and it was a reputation he maintained within the Venezuelan school of design. Jorge F. Rivas Pérez describes and focuses Zitman's activity as The Decade of Design / 1947-1957: a crucial chapter in the production of conceived and manufactured furniture in Venezuela. After the company's closure, Zitman decided to give up his entrepreneurial life and moved to the island of Grenada, where he devoted himself entirely to painting and began to assert his character as a sculptor.

In 1961 he traveled to Boston in the United States to participate in an exhibition of painting and design. That same year he returned to Holland with the desire to study casting techniques. In 1964 he worked as an apprentice in the foundry of the sculptor Pieter Starreveld and then returned permanently to Venezuela. On his return, he was hired by the Central University as a professor of design. The following year he began to work more intensively on small-format sculpture modeled directly in wax. In 1971 he exhibited for the first time at the Galerie Dina Vierny in Paris, and from then on, he devoted himself exclusively to sculpture. During these years he held several individual exhibitions in Venezuela, France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, the United States, Japan, and other countries. He won several national and international awards.

Zitman participated in several international exhibitions such as the Budapest Sculpture Biennial and the São Paulo Biennial, the FIAC in Paris, and the ARCO fair in Madrid. His solo exhibitions include the Galerie Dina Vierny in Paris, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Caracas, the Tokoro Gallery in Tokyo, the Museum of Modern Art in Bogotá, and the Beelden Zee Museum in Scheveningen, the Netherlands. His sculptures seek to reproduce and exaggerate the morphology of the indigenous people of Venezuela, especially the female figure. His works are in private collections and museums in various countries, such as the National Art Gallery of Caracas and the Museum of Contemporary Art of Caracas in Venezuela, and the Musée Maillol in Paris.

Clara Porset born in Cuba (May 25, 1895 – May 17, 1981), was a furniture and interior designer who lived and worked in Mexico for the best part of her working life, and it is there she is considered a pioneer in furniture design.

Born into a wealthy Cuban family in 1895, Porset had the opportunity to travel and, as a result, collected a wide range of artistic and political influences. She studied in New York from 1911 to 1914 and attended technical courses in architecture and design in her home country of Cuba. In 1925, Porset returned to New York City and continued her studies in art, architecture, and design at Columbia University's School of Fine Arts and the New York School of Interior Design.

In the latter part of the 1920s, Porset traveled to Europe where she met Bauhaus teachers Walter Gropius and Hans Emil "Hannes" Meyer, with whom she remained in contact for many years. From 1928 to 1931, she studied architecture and furniture design at the designer and architect Henri Rapin's Paris studio and attended classes at the École des Beaux-Arts, the Sorbonne, and the Louvre.

She returned to Cuba in 1932, where she served briefly as artistic director of the Escuela Técnica para Mujeres (Technical School for Women), but due to her outspoken political views, she was forced to leave Cuba in 1935. She then moved to Mexico, where she met and married the painter Xavier Guerrero. Through their partnership, she was introduced to the folk arts and the prominent artists of the country, who in turn influenced her career. The couple collaborated on a proposal for the Museum of Modern Art's (New York) 1940 competition, Organic Design in Home Furnishings. The pair were the first time Latin American designers included in the museum's call for proposals.

In the 1950s, Ruiz Galindo Industries (IRGSA), regarded as the best furniture manufacturer in Mexico, considered Porset, the finest designer. They hired her to design and develop furnishings for architectural projects they had going on in Mexico. She signed a contract to develop two collections: The E-series (quality wooden office furniture) and H-series (metal office furniture). These lines became popular in Mexico due to their: quality, high design, durability, and relatively low cost.

In 1952, Porset curated the exhibition Arte en la vida diaria: exposición de objetos de buen diseño hechos en México (Art in Daily Life: An Exhibition of Well-Designed Objects Made in Mexico) at the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes (Mexico City).

Porset returned to post-revolutionary Cuba in 1959. President Fidel Castro commissioned her to design the furniture for the school of Camilo Cienfuegos, an institution symbolic of the new society envisioned by revolutionaries. Before returning to Mexico in 1963, she also created furniture for several other universities after her plans to establish a new design school in Cuba were not comprehended.

In 1969, designer Horacio Durán founded an industrial design program at the Escuela Nacional de Arquitectura (now part of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM) and invited Porset to give a seminar. She continued teaching for the remainder of her life.

The Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes recognised Porset as a pioneer of modern Mexican design by awarding her a Gold Medal in 1971. The Clara Porset Design Prize has been awarded to Mexican design students since 1993.

Furniture designer Don Shoemaker was born in Nebraska to an affluent family. During the 1930s, he studied at the Art Institute of Chicago. In the late 1940s, he married and subsequently, on his honeymoon, fell in love with Mexico. He loved the country so much that later in the 1940s, he moved to Mexico with his wife. Shoemaker lived and painted in a town called Santa Maria de Guido, overseeing the City of Morelia in Michoacán.

Don and his wife Barbara lived in harmony with nature, growing many rare plants in their greenhouse. Don became inspired by the tropical woods of Mexico and began to manufacture furniture from these precious timbers. What began as a small factory in the late 1950s became known as Señal S.A and grew to where Don employed more than a hundred skilled artisans. Soon he became an important figure in the economic and cultural life of his adopted town. Señal S.A brought new wealth and an economic boost to the town, and Dom was known for his warm and charitable heart.

The furniture designed for Señal S.A by Don were modern interpretations of traditional Mexican furnishings. Many of his iconic designs were inspired by traditional Mexican woodwork. The pieces made from Cocobolo, a Mexican rosewood, and other precious woods were highly sought after. The furniture was exported to showrooms in Chicago, Los Angeles, Houston, and large Mexican cities. His designs were liked very much by wealthy Mexican families who had complete sets decorating their homes.

His most well-known designs include the Sling Sloucher chair, Sling Swinger chair, the Suspension stool, and his Coffee tables, which were also very popular. Don Shoemaker’s furniture, chairs, tables, and decorative objects remain popular worldwide.

Don passed away in 1990 and handed the business over to his son George, George however, died in the early 2000s, and the company disappeared.

Cynthia Sargent was a mid-century textile designer. Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the spring of 1922, later in life, Cynthia studied dance and painting from Joseph Albers, block-printing, and art history with Robert Motherwell, Meyer Schapiro, and other well-known artists of the day.

Cynthia married an architect named Wendell Riggs, and in 1951, the two emigrated to Mexico, where they built a legacy of art and design. Through her textile Works and entrepreneurial endeavors, she fostered a sense of community and a new respect for artisanal work.

The couple started up the firm Riggs-Sargent, which developed many successful lines of printed and handwoven fabrics. During the first year of their business endeavor, they both were invited to participate in a crafts exhibition organized by Clara Porset and held at Museo Bellas Artes.

Rugs became the main focus of their studio at the beginning of the 1960s and the primary seller at Riggs-Sargent. Cynthia designed the work and supervised the handhooking. The rugs were extremely popular with decorators, and the press described her work as paintings in wool “…which you hang on the floor.”

They also established the Bazaar Sábado and the organizations Club Pro Arte and the Centro de Diseño, galleries and gathering places that promoted the work of the city´s artists and designers. Cynthia Sargent died in 2006, but her work continues in its popularity, and its beauty never fades.

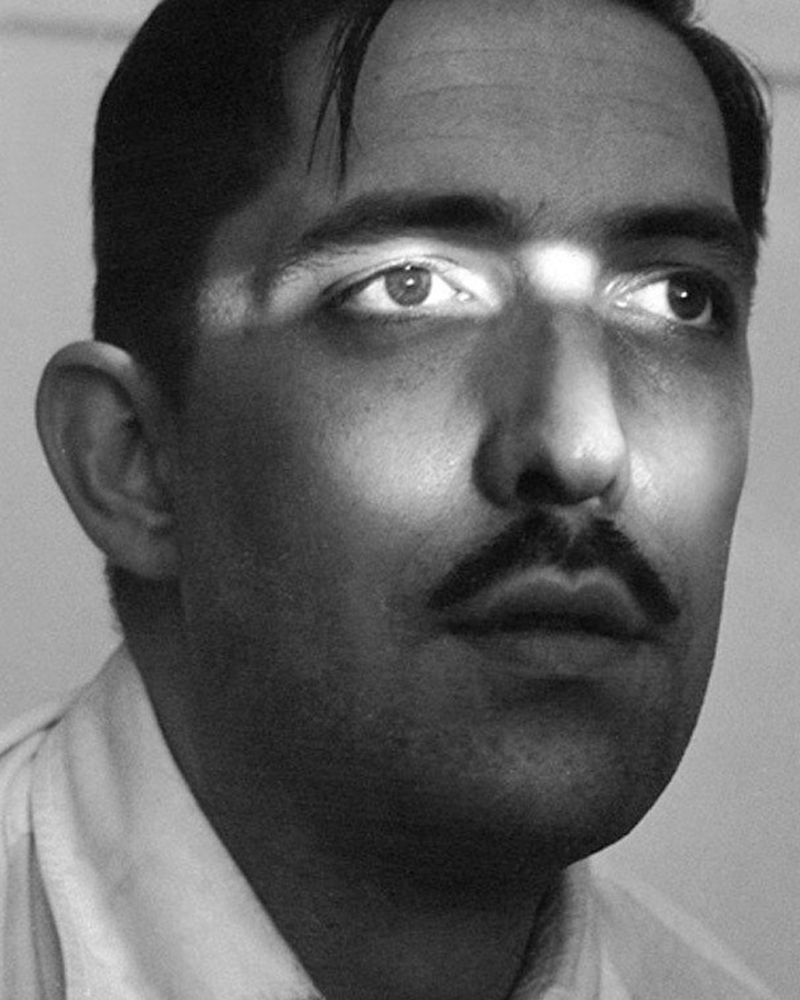

Geraldo de Barros (Chavantes 27th February 1923 - Sao Paulo 17th April 1998) was a prolific artist across various media. He experimented relentlessly with utopian ideals, divulged through his exploration of furniture design from the mid-1950s till the late 1980s. While undoubtedly Brazilian, he drew much of his aesthetic influences from European avant-garde culture, from De Stijl and Bauhaus to Gestalt psychology.

Starting his artistic career in painting, he then found himself in photography; de Barros held a successful exhibition "Fotoformas" in 1950, the title being a reference to Gestalt. His artistic trajectory put him at the forefront of experimental photography, and in 1951 he was awarded a scholarship from the French government, which allowed him to travel and study in France. While in Europe, he also traveled to Zurich, where he met Max Bill, a former Bauhaus graduate who was collaborating at the time with the Scholl Foundation on the creation of a new design institute that had the ambition to continue the Bauhaus traditions with the integration of the human and technical element in design teaching and practice. Max Bill invited Geraldo to visit the institute (not officially opened till 1953) in Ulm, Germany, where he consequently spent some weeks attending workshops and was subsequently heavily influenced by what would be Max Bill's idea of Gute Form. The essence of Gute Form was the belief that objects, if carefully designed, can bring art into everybody's home, and art can be a way not only to reflect on the world but to make visible connections and abstractions without using verbal language. Here we can see a clear link between Geraldo's future ideals for furniture design and Bill's philosophy.

After his return to Sao Paulo and following further success as an artist, a change of government was to change Brazil. A new wave of investments from Europe was inaugurated by the president with the motto 'fifty years in five.' Modernization and industrialisation were being imposed from above. Geraldo de Barros, along with a Dominican Priest, Friar João Batista Pereira dos Santos, embarked on his first and most crucial venture as a furniture designer. In 1954 Unilabor was created and became a mechanism of modernization from below.

Unilabor was unity in work and a unity through work. The workers ran a self-managed e factory; it was a system of production that aimed to unify not only form and function but also a living community and production processes. This balance of forces certainly informed the discreet beauty of Unilabor furniture pieces. The tension that affected the products of the national wave of industrialization is clearly absent from the relaxed, warm lines of these pieces. In its context, Unilabor, in fact, quickly became a social model. It was a working environment that was perceived as healthy. It was created to be less a company, more a community.

The other two founding members of Unilabor, the engineer Justino Cardoso and the toolmaker Antônio Thereza provided specialist knowledge and skills while Geraldo de Barros made the drawings. Geraldo's approach to design was very humanistic. He intended to socialise art and its messages. By using the products, he designed for their daily activities, owners of Unilabor furniture were using art. For Geraldo, the designer's role consisted in mediating between society and industry, aiming to solve the tension between quantity and quality. João Batista and Geraldo agreed that if market trends ruled manufacturing, it eventually became informed by quantitative interests only, with a disadvantageous effect on the quality of the product and the working and living conditions of the workmen. Despite its ideals, Unilabor eventually ran into economic difficulties and eventually only lasted thirteen years.

Geraldo then dedicated himself to the furniture factory he created in 1964 with a former Unilabor cabinet-maker, Aloísio Bione. Rather than being a company with a clear aesthetics, as many Italian furniture manufacturers of the nineteen-sixties, to which it can be compared, Hobjeto Indústria e Comércio de Móveis was characterised by extreme flexibility of the form, which stays constant throughout the several lines of products Geraldo de Barros designed over the years. The furniture was also progressive, evolving to follow the dominant shapes of the time: more angular and squarer when the furniture was more geometric; more rounded when the products had softer lines; and finally made of long, continuous lines when Hobjeto introduced a furniture family made with tubular elements.

Both in the case of Unilabor and Hobjeto, interestingly, the essential component of Geraldo's design philosophy is the chair. This is particularly fascinating, especially if we consider that at the time, modular systems were prevalent amongst most industrial designers. While armchairs inspire intimacy and solitude, chairs, like sofas, have a significant social aspect. The proportions of Geraldo's chairs multiply into larger furniture items, and the environments arranged for publicity photographs are often constructed around the chair's presence.

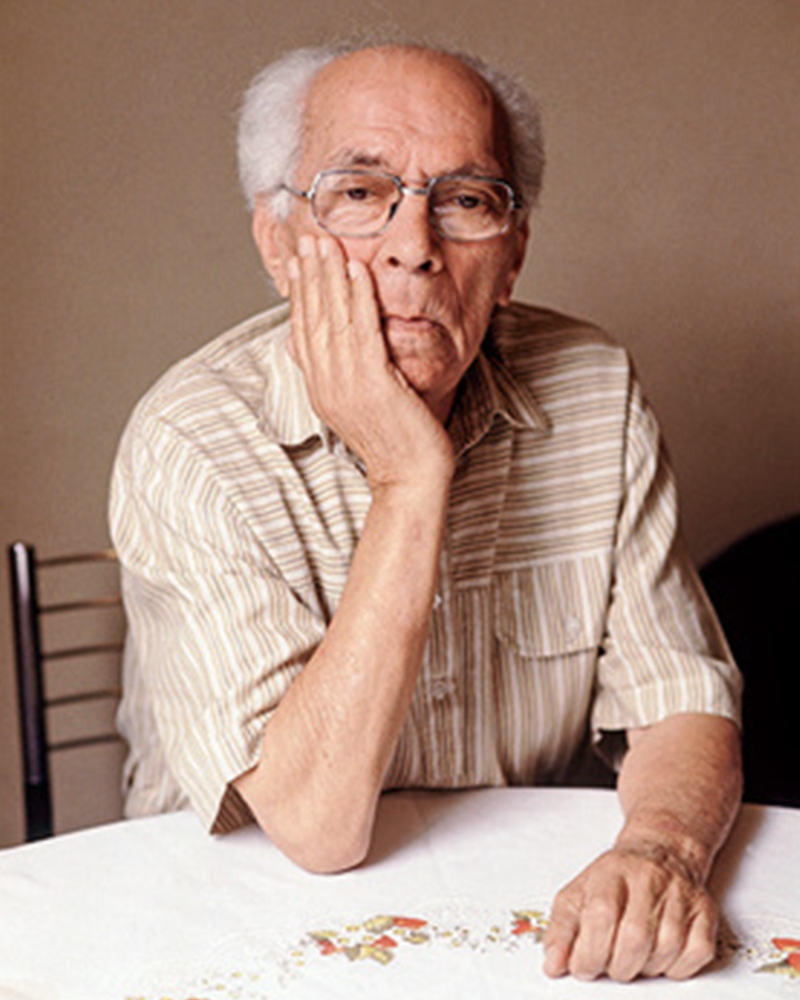

Joaquim Tenreiro (Melo Guarda, Portugal 1906 - Itapira Sao Paulo 1992) was a, sculptor, painter, engraver and designer. Born into a family of joiners, at the age of two, his family emigrated to Brazil, settling in Niterói, Rio de Janeiro. In 1914 he returned to Portugal. He helped his father with woodwork projects and began painting classes. He returned to live in Brazil between 1925 and 1927. In 1928, he moved to Rio de Janeiro permanently. He studied drawing at the Portuguese Literary Lyceum and enrolled in the Liceu de Artes e Ofícios. In 1931, he joined the Bernardelli Nucleus, a group created in opposition to the academic teaching of the National School of Fine Arts - Enba.

After some years of dabbling in as a painter, Joaquim traversed his talents and went back to wood, "I stuck with painting up to a point, but gave it up because I could not stay away from the wood-working shop...what kept me going was furniture" (Soraia Cals, Tenreiro, Rio de Janeiro, 1998, p. 190). He designed for Laubish & Hirth, Leandro Martins, and Francisco Gomes, specializing in French, Italian, and Portuguese furniture. A decade later, he founded Langenbach & Tenreiro, which would become renowned for its modern furniture designs. Tenreiro's partner insisted on selling traditional furniture, while Tenreiro argued for a modern sensibility. In the early years, Tenreiro designed both conservative and modern furniture for their inventory. However, by the late 1940s, the modern movement had taken hold in Brazil, and when only Tenreiro's original pieces sold, the shop dedicated itself solely to contemporary designs.

His success as a designer commenced in 1942 when he was commissioned to design and manufacture the furniture for the residence of Francisco Inácio Peixoto, in Cataguases, in the interior of Minas Gerais. The residence was designed by architect Oscar Niemeyer (1907 - 2012), to whose work Joaquim identified beautifully, creating the commissioned pieces in assimilation with the purity of Niemeyer's architectural forms. The furniture Tenreiro designed for this project were the first pieces made by him in which it is possible to distinguish the sober beauty of form and the wise use of Brazilian wood so identifiable in his works throughout the next two decades.

The Light Armchair (ca.1942), made in ivory wood, with a darker version in imbuia, was upholstered in fabric stamped by Fayga Ostrower (1920 - 2001) and one of his most famous pieces. The chair was conceived according to his principle that Brazilian furniture should be light; in Tenreiro's words, lightness has nothing to do with the weight itself but with grace and functionality. Testimony to the ideological alignment of modern Brazilian furniture, Tenreiro's design is rooted in the principle of stripping back the unnecessary to demonstrate the true beauty of an object while maintaining the utmost function.

His acclaimed Three-legged Chair (ca.1947) associates geometry with colour through the particular use of Brazilian woods. It is chromatically innovative composed of a combination of timbers (imbuia, roxinho, rosewood, ivory, and cabreúva), all with varying shades. Tenreiro spoke of the technical difficulties in creating these chairs—of combining woods that retain different levels of humidity, dry at varying rates, and expand and shrink differently—but the design's success speaks to his technical prowess and to his artistic vision. Like other Tenreiro furniture of this period, it has a light and luminous appearance, contrasting with the solid and sober furniture he previously created for Laubisch & Hirth.

In some chairs and armchairs, Joaquim explored weaving natural materials such as straw that evoke indigenous braiding and basketry. The use of wood and natural fibers is generally associated with adapting furniture to a tropical climate; together with these organic compositions, other works of Tenreiro's, such as the Structural Chair, present straight lines, and geometric elements, creating structures from both wood (1957) and metal (1961). Tenreiro's deep knowledge of wood is illustrated through the poetic features in his works.

At the end of the 1960s, he closed his stores and stopped manufacturing furniture for personal and market reasons. Instead, he returned to the realms of painting and dedicated himself to sculpture. Techniques discovered during his design days can be seen in his sculptures. For example, the chromatic composition of woods he employed in the Three-Foot Chair was later resumed in some sculptural reliefs, in which the artist explores the differences in color, textures, and the veins of wood; his work Circles (1979) demonstrated this.

Tenreiro's productions are renowned for their combination of modern characteristics that define mid-century Brazilian furniture, such as simplicity, the use of local materials, function, and artistic beauty.

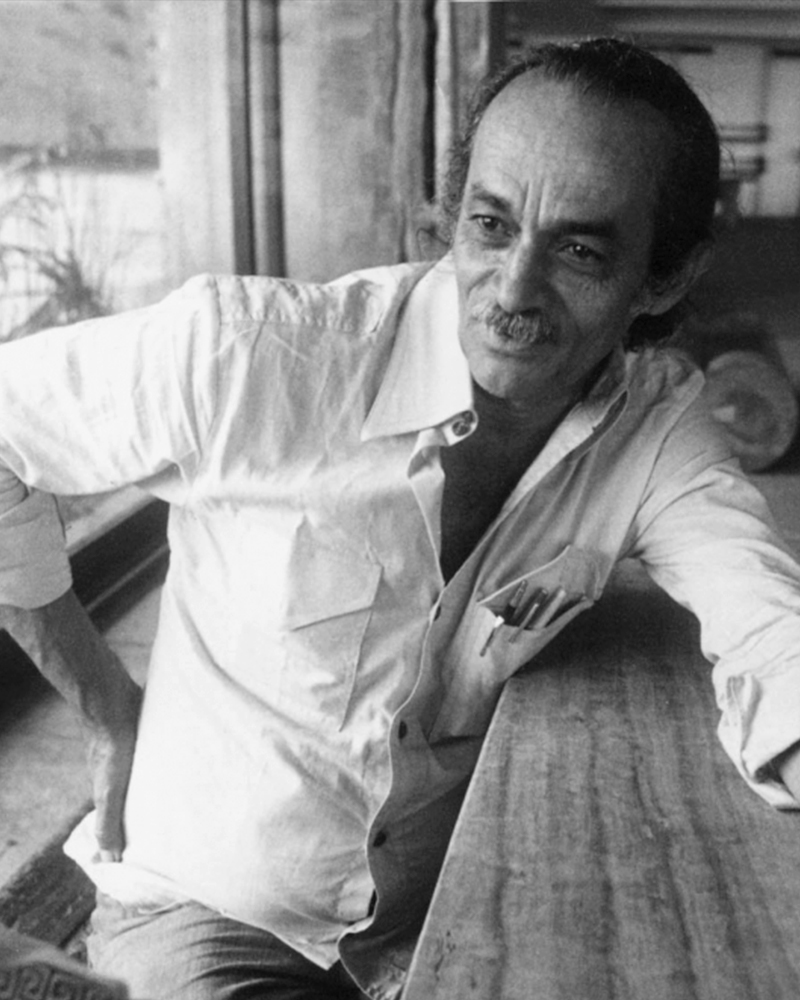

José Zanine Caldas (Belmonte, Bahia, 1918 - Vitória, Espírito Santo, 2001) was an architect and designer. Caldas stands in Brazil for his exploration of the constructive qualities of Brazilian woods, defining his work with a warm rustic ambiance, working on both high-end residential projects and famous constructions.

Never actually training as an architect, he started working in the 1940s as a designer at Severo & Villares and as a member of the National Artistic Historical Heritage Service (Sphan). He opens a maquet studio in Rio de Janeiro, where he worked between 1941 and 1948, and, at the suggestion of Oswaldo Bratke (1907-1997), moved the studio to São Paulo, from 1949 to 1955. The studio served important modern architects of the two cities and was responsible for most of the models presented in the book Modern Architecture in Brazil, 1956, by Henrique E. Mindlin (1911-1971).

During the 1940s, he also began developing and researching at the Institute of Technological Research of the University of São Paulo (IPT/USP) and was first introduced to plywood. In 1949, he founded the Fábrica Móveis Artísticos Z, intending to produce large-scale industrialized furniture, good quality and affordable, the furniture was to be materialised using plywood sheets. This method minimised material waste and the need for artisan skills, as the parts were mechanically produced, and the use of labor was only needed for the assembling of the furniture.

His time at Móveis Artísticos Z, in 1953 was relatively short-lived and he left the company in 1953 and instead worked on landscape projects until 1958 in São Paulo, when he moved to Brasília, where he built his first house, also in 1958, and coordinated the construction of others until 1964. Appointed by Rocha Miranda to Darcy Ribeiro (1922-1997), he joined the University of Brasília (UnB) in 1962 and taught modeling classes until 1964, when he lost his position due to the military coup. He set off and traveled through Latin America and Africa, an experience that remarkably affected his work.

On return to Brazil, he built his second house, the first of a series of projects in the Joatinga region of Rio de Janeiro. In 1968, he moved to Nova Viçosa, Bahia, and opened a workshop, which ran up until 1980. His experience in the Bahian city was shaped by his renewed love and contact with nature, and he began working closely with environmentalists. In one of these collaborations, he participated in the project of an environmental reserve with the artist Frans Krajcberg (1921-2017), for whom he also designed a studio in 1971. The furniture he designed during this period is reflective of his ecological sensitivity. His works were constructed with crude wooden logs, whose twisted lines inspire his drawings.

It is also in Nova Viçosa that the architect builds the Casa dos Triângulos (1970) and casa da Beira do Rio (1970), in which he adopted a very artisanal construction system with typical woods of the region. According to the historian and architecture critic Roberto Conduru, Caldas' performance was relevant for the diffusion of environmental values in architectural projects: a "taste for the alternative and the rustic was disseminated throughout the Brazilian territory [...], encouraged by environmental preservation campaigns, by the wear and tear of the current models in reinforced concrete and by the re-emergence of the regionalist ideal in the international panorama "1.

Between 1970 and 1978, he kept an office in Rio de Janeiro, returning in 1982. In 1975, the filmmaker Antonio Carlos da Fontoura made the film Arquitetura de Morar, about the houses of Joatinga, with a soundtrack by Tom Jobim (1927-1993), for whom Caldas designed a house. The architect's work was exhibited two years later at the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro (MAM/RJ), at the São Paulo Museum of Art Assis Chateaubriand (Maps) in Belo Horizonte, and the following year at Solar do Unhão, in Salvador.

Between 1980 and 1982, The Helium House Olga Jr was designed and built in São Paulo. Caldas outlined the plans for the construction, sourcing all the wood, the actual assembly of the house was carried out by the owner. The house was defined by a wooden structure that stands out from the fence walls, the clay tile roof of wide eaves, and the demolition materials that give the building rusticity, warmth, and nostalgia. The house was similar to those built in the 1970s for Eurico Ficher and Pedro Valente in Joatinga.

In 1983, Calders founded the Center for the Development of Applications of The Woods of Brazil (DAM), and gave it to UnB in 1985. During this period, he proposed the creation of the Escola do Fazer, a teaching center focused on the use of wood for the construction of houses, furniture and utilitarian objects for the low-income population.

Even though much of Calder's early work was centered around building houses for the elite, in the 1980s, the designer dedicates himself to the DAM, where he rigorously researched popular housing based on artisan construction processes and where users participate in the construction process. At the Brasília unit, he developed prototypes of popular houses with eucalyptus logs as a structure and sealing in soil-cement, betting on an ideal of self-construction already tested at Casa do Nilo, in São Gonçalo, Rio de Janeiro. From that moment on, as occurred with his furniture designs, Caldas adopts the use of crude wood logs rolled - and no longer rigged - usually discarded, allied to demolition materials, which radicalize the effect of rusticity and warmth. This method also spread to non-residential projects, such as the Barra das Princesas Agropecuária S. Fazenda Chapel in Araguaia, Mato Grosso, the chapels of Guarapari, Espírito Santo, and Itapissuma, Pernambuco and Pousada Pedra Azul, in Domingos Martins, Espírito Santo.

Calder's success, without a doubt, was thanks to his modeling studio, where his clientele noticed his ability to propose solutions to the design problems he identified during the execution of the models. In 1986, however, the publication of his work in the magazine Projeto n. 90 initiated a controversy in the Regional Council of Engineering and Architecture (Crea) over the fact that Caldas was self-taught. Several architects jumped to his defense, among them Lucio Costa (1902-1998), who awarded him five years later, at the 13th Brazilian Congress of Architecture in São Paulo, with the title of honorary architect given by the Institute of Architects of Brazil (IAB). In 1989, he was reinstated to his post at UnB, but did not teach. That year, he traveled to Europe, where he designed residences in Portugal and taught at the École d ́Architecture in Grenoble, France. The Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris held an exhibition of design pieces in 1989, the same year he received the silver medal from the College of Architects of France.

The integration of industrialism of the 1950s and the ecologism of the 1970s was a considerable challenge to many industrial designers. This was a theme that was very much present in Calder's work. It was this debate that removed the architect from the proposal of serialisation carried out in Moveis Z. It brought him back to craftsmanship and the indigenous language of Brazil, the house of the architect Carlos Frederico Ferreira (1906 - ca.1996) and Casa Hildebrando Accioly de Francisco Bologna (1923), are both examples of Calder's connection with his grounded roots. José Zanine Caldas has left a significant legacy, permeating both serial production and the priority of native manufacturing.

Martin Eisler (Vienna, Austria, 1913 - São Paulo, Brazil, 1977) was an architect and furniture designer. He was part of a group of European architects and designers who left Europe during the chaos of the Second World War and went to live and work in Brazil. Eisler stood out amongst this group of creatives. His work was at the forefront of modern furniture design in Brazil, which flourished through the 50s and 60s. Eisler's work in partnership with Carlo Hauner (1927-1996) was of particular significance.

Eisler left Europe in 1938 due to the rise of fascist regimes. He first lived in Argentina, where he was settled and worked as an architect, set designer, and interior designer. Eisler opened up an interior design firm Interieur Forma. In 1940, he married Rosl Wolf, the daughter of German immigrants.

Born in Brescia in 1927, Carlo Hauner studied technical drawing and drawing at the Brera Academy in Milan, Italy. In 1948 he successfully participated in the Venice Biennale, after which he moved to Brazil, where he dedicated himself to the design of textile, ceramics, furniture, and architecture. After purchasing a factory from Lina Bo Bardi and her husband Pietro Bardi, he quickly founded a furniture production company, renaming it Móveis Artesanal.

In 1953 Hauner met Martin Eisler, who was looking for help to produce furniture for the home of his brother-in-law, Ernesto Wolf. Eisler reached out to Hauner, marking the beginning of a flourishing partnership. The two men connected, and with Wolf's financial backing, they opened Galeria Artesanal (a store for their company Móveis Artesanal) on a busy street in São Paulo.

Being highly ambitious and with an eye on the international market and the upcoming office market, Móvies Artesanal later changed into Forma. Along with Oca, Forma became one of the biggest names in Brazilian furniture production. Eisler attracted exclusive license to sell Knoll furniture, bringing big names in international design such as Mies Van Der Rohe, Charles Eames, and Harry Bertoia to the Brazilian furniture market. Hauner and Eisler's designs are characterized by Brazilian woods, thin tubular frames, and range from furniture to ceramics and textiles. Some of their most famous designs are the "rib" lounge chair, the "concha/haia" chair or "reversible" lounge chair, both shown in this exhibition. In 1958 Hauner decided to return to Italy to open Forma di Brescia, which catered to, e.g., the embassy of Brazil in Rome and Vatican City. Eventually, Hauner sold his part of the company, leaving Eisler solely at the helm to paint and make wine on Salina, a little isle just above Sicily. After a fulfilled life, the artist, designer, and serial entrepreneur died in 1997. Forma prospered during the 60's and 70's, until Martin Eisler died in 1977. His original company in Argentina still exists and, at the moment, is the sole heir to Hauner and Eisler's Heritage. Although Hauner and Eisler designed and produced many pieces, the depth and quality of their work outlined is only the beginning of their lasting impact on the design world.

Michael van Beuren was born in New York in March 1911. He arrived in Mexico in 1937 looking for opportunities, keen to work as an untitled architect. First, he spent a season in Acapulco, took over the construction and interior design of the Flamingo's Hotel bungalows, and headed to Mexico City. His first jobs in the capital were a series of houses that would carry numbers 1, 2, and 3 on Liverpool Street.

Once settled in the country, Van Beuren realized that it would be difficult to practice architecture without going under the title of an architect. Still, with his skillset and the knowledge he acquired in the Bauhaus, he ventured into the furniture industry. He offered Mexican society a new type of design, contemporary in nature and adapting to the modern architecture that was starting to dominate the design society of Latin America.

In the late 1930s, he began to design furniture with his colleague of the Bauhaus, the German designer Klaus Grabe. They formed a small company that operated under the name of Grabe & Van Beuren.

Following the formation of his first company, Michael van Beuren created Domus, a second furniture firm and probably his best known. The brand opened its first store at number 40 on Hamburg Street in the 1940s; this company served as an umbrella for various brands that flooded the Mexican market with exciting designs and a much more international and modern approach, leaving behind the "Mexican style" created in the search for a national identity.

In 1941, Van Beuren participated in the Organic Design for Home Furnishing contest, organized by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This contest, for the first time, included Latin American designers. This contest was where the pair formed by the marriage of Clara Porset and Xavier Guerrero and the trio formed by Michael van Beuren, Klaus Grabe, and Morley Webb won an award. After this, the chaise lounge that Michael had named Alacrán went for sale in Bloomingdale's for 69.98 dollars.

In 1950 Fredderick T. van Beuren, Michael's brother, was appointed to overlook the production side of the workshop to make it more efficient and increase the scale to actual factory size. The company then became Van Beuren S.A of C.V. Within five years, Van Beuren, S.A of C.V was already able to produce in series, which allowed them to make several lines simultaneously and preserve quality.

In addition to Domus, Van Beuren produced other successful lines, which were developed at a time when Mexico was looking for a more international aesthetic. For example, the Calpini brand was reported to have a strong Bauhaus influence, according to Espacios magazine in 1951, and Descapóls in 1961. It was one of the more famous lines of the period and had significant sales success in The Port of Liverpool.

Michael van Beuren continued designing and retired to live in Cuernavaca, where he died in 2004. Today his furniture represents one of the most fruitful moments of furniture production in Mexico and has become an essential part of Mexican twentieth-century design history.

The 1950s in Venezuela were characterized by material progress and renewal. The architecture and furniture of simple geometric lines showed the lifestyle of a country that went from rural to urban. Lampolux, Decodibo, the Hatch Gallery, and Capuy were shops and galleries introducing modern furniture to Venezuela. Miguel Arroyo was the first to assume modern furniture design in these lands. He was remembered for his management as director of the Museum of Fine Arts and his ceramics, research, and arts teaching career.

Miguel Gerónimo Arroyo Castillo was born in Venezuela on August 28, 1920, and died on November 3, 2004. He was a ceramist, professor, curator, museographer, writer, critic, historian, furniture maker and interior designer, and a promoter of the arts and their conservation. He pioneered furniture design in Venezuela.

From a young age, it was clear in which direction Arroyo's career path would lead. In 1939 he traveled to the United States as an assistant to the painter Luis Alfredo López Méndez, who was commissioned to make the murals for the Venezuelan Pavilion at the New York World's Fair whose thematic axis was "the future". Later, in 1946, Arroyo was awarded a scholarship from the National Ministry of Education to study at the Carnegie Institute Technology in Pittsburgh, where he approached the applied arts.

In 1949, the Gato store, a pioneer in marketing ornamental and "design" objects opened. The store was in a house on Los Jabillos Avenue in Sabana Grande. Arroyo produced ceramics, enamels, and modern furniture for the new enterprise. In the 1950s, he joined the avant-garde group The Dissidents, within which he manifested his ideas around the role of design in Venezuelan society. For Arroyo, abstractionists cared "for architecture, industrial design, crafts, and imagine a state of integration of the arts according to which they are present not only in the large mural or in the polychrome of buildings, but also in the design and selection of materials and color of objects as common as a saucepan can be."

Modern architecture boomed in Caracas of the Fifties, the City University designed by Carlos Raúl Villanueva, and the Urbanization Bello Monte promoted by Inocente Palacios, was commissioned. However, there were few modern furniture firms conceived in the country.

In Latin America, the modernist aesthetic of furniture was expressed by introducing local elements such as cultural identity, environmental conditions, and the rescue of artisanal traditions. The result was usually the contrast between the new and the old. In an article written for Magazine A in 1954, entitled: Modern Furniture for a Colonial House, Arroyo testified to his creative process for furnishing Alfredo Boulton's beach house in Pampatar, New Sparta state.

Arroyo investigated colonial furniture in Mexico by accepting the commission, which began with carefully observing specimens exhibited in the Quinta de Anauco. He concluded that the main characteristics of colonial furniture were sobriety, material (wood), preference for curved lines, and craftsmanship. This information was the basis for designing the dining set, a wardrobe, the seating, and the rooms, which formally exhibit an authentic integration of colonial aesthetics with the modernist language. Several of these objects were in the exhibition Interior Modern, mounted in the Sala Trasnocho Arte Contacto in 2005.

Between 1950 and 1959, Miguel Arroyo designed more than one hundred pieces of furniture, both for individual projects and companies. He mainly worked with native woods and often collaborated with the cabinetmaker of Canary origin Pedro Santana. The woods were used according to their texture, hardness, and color and sometimes combined with other materials such as metal, marble, and formica.

There were also opportunities in which Arroyo's furniture evoked the visual rhythm of geometric abstraction at an aesthetic level. He created the table for the Mendoza family with the concept of "empty-full".

After the sixties, Arroyo moved away from furniture design without neglecting his passion altogether. He was called to participate in a team of advisors to the La Estancia Center, the first national institution conceived to promote design and photography in the mid-1990s. He continued to act as an advisor to different cultural projects and as a researcher until his death in 2004.