Side Gallery

Side Gallery

WishlistFollow

Follow

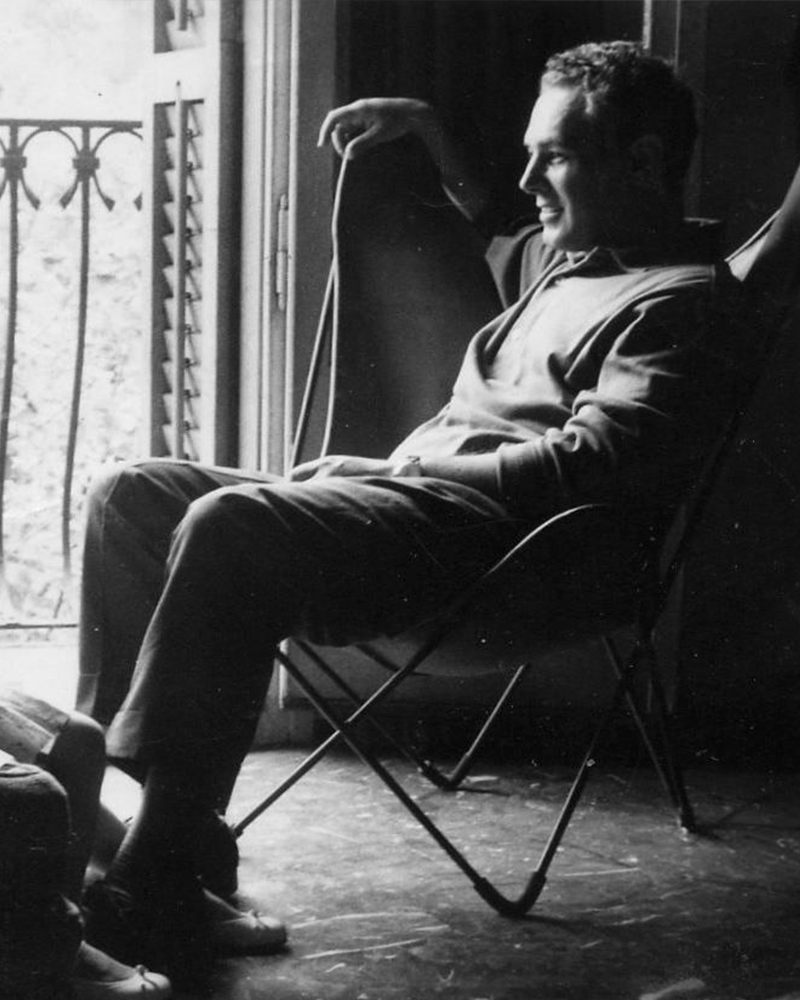

Antonio Bonet Castellana, born in Barcelona on August 13th, 1913, and died in Ibídem on September 12th, 1989, was a Catalan architect, urban planner, designer, and resident of Río de la Plata (Argentina) for the best part of his life.

Bonet was trained in two ways: on the one hand, from the teaching he received at University, and on the other, from the working relationship, he formed with J. Lluis Sert, who was involved in the Modernist Movement leads to the formation in 1930 of the GATPAC.

In 1935, he became a collaborator in Catalonian architects Jose Luis Sert and Torres Clavé and a member of the GATPAC until 1935. During this period, Bonet worked on the Roca jewelry projects, the houses in Garraf, the kindergarten, and the MIDVA stand, for which he was awarded first prize at the Barcelona Decorators Show. In 1933 he attended the historic cruise aboard the Patris II, which took him to Athens, where he participated in drafting the Athens Charter, a key event for the architectural culture of the 20th century. During the lecture, the functions of living, working, resting, and circulating were enunciated as the fundamental elements of urban development. On this same trip he met Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto.

In 1936, as soon as he finished his architectural studies, he traveled to Paris to join Le Corbusier's studio. In Le Corbusier's studio, he projected the house made by Bonet at the request of the master: the Maison Jaoul. He also designed the main building for the Liege International Exposition, the Water Pavilion. For this work, he incorporated surrealist ideas into the functionalist architecture of the moment, one of the aspects that would later characterise his work.

In 1937 at the International Exposition in Paris, Le Corbusier presented the Pavilion Des Temps Nouveaux. Bonet collaborated with Sert to realise the Spanish Pavilion, whose symbolic character was fundamental, attending to the concept of unity sought at that historical moment. This construction linked the different works of Spanish artists on display (Miró, Calder, and Picasso), integrating them into architecture.

During his tenure at Le Corbusier's studio, he met two young Argentine architects: Juan Kurchan and Jorge Ferrari Hardoy. The prospect of war on the horizon, coupled with his new friendships, led Bonet to move to Argentina in 1938. Once there, he formed, together with Kurchai and Jorge Ferrari, the Austral Group, which acted as the first reference to modern Argentine architecture and was in charge of spreading the basic ideas of the modernist movement and offering profound criticism. He set out to study the country's urban planning problems and suggest solutions.

In June 1939, they published the Group's manifesto under the title Will and Action. They defended the superimposition of some values of surrealism to the rationalist training of architects and incorporated the individual's psychological needs into the strict functionalism of the modern movement. This manifesto exposes Bonet's stance towards architecture and his effort to establish continuity with each area's landscape, techniques, and materials.

Together with his partners, he is credited with the legendary BKF chair, although its authorship is finally assigned to Jorge Ferrari Hardoy.

Antonio Bonet built between 1938 and 1939 what is considered the first modern construction in Buenos Aires, a residential building on Paraguay and Siupacha streets. Later he built buildings such as the OKS house in Martínez (1954-1958) or the Rivadavia tower in Mar del Plata (1956). During the 1940s, he settled in Uruguay, where he worked on the urban project for Punta Ballena, Maldonado, and built the hotel restaurant La Solana del mar (1947), the La Gallarda house for the poet Rafael Alberti, and the Berlingieri house ( 1946), where Catalan vaults extend the dunes of the landscape. In these creations, freedom of form, an emblematic characteristic of Bonet, is present without abandoning his rationalist background.

Back in Argentina in 1950, he met again with the mechanisms of the defunct Austral Group to participate in the drafting of the Buenos Aires Plan. Antonio Bonet was undoubtedly one of the definitive links to European avant-garde architecture in Latin American architects.

In theory, he considered architecture as a matter of order in human life and believed that the architect's activity extended from the conception of a piece of furniture to the planning of a city. One constant was the effort to integrate the varying scales of the human habitat, investigating new materials and forms to achieve architectural spaces and furniture that would be at the service of society.

It is necessary to emphasize Bonet's importance to the dynamics of space; It creates different perceptual sensations when playing with changes in scale, the various definitions that light produces through the closing, and the movement of floors and ceilings. Bonet designed from a general approach, which allowed him to see the intention of the work, through the patios, terraces, and galleries, to the architectural elements such as cornices, railings, or closings.

Bonet was sympathetic to suggestive and imaginative environments manifested in formal resolutions and the approach to spatial situations. For example, the feeling of abnormality created by the support of heavy structures by columns that give the impression of being diluted: Casa Oks (1955), La Ricarda (1953), and Castanera (1964). He also used the pressure of heavy concrete structures supported at low heights, such as in the Terraza Palace building (1957), the Silver Sea, or the Torre del Barrio Pedralpes in Barcelona (1973).

On his return to Spain, he followed this trend: he designed sculptural towers, such as the Cervantes (1955) or the Urquinaona Tower (1971), the most significant within this line, the project for Plaza de Castilla, Madrid (1964) and the Torre Rosas (1967).

His connection with the Mediterranean spirit manifested in the choice of materials and the vision of his buildings. The public and private borders were raised, blurring their limits and resulting in a new relationship. They were characteristic of his work of intermediate climates. He joined these two conclusions in the vaults to cover spaces uniting the traditional techniques and materials of the place. Some examples are: houses in Martínez (1940), Berlingieri's home (1947), a work in which it is easy to see Mediterranean influence; in this case, the vaults define a bearing and spatial direction, unlike in the La Ricarda (1953) made on his return to Spain, where the concept evolves with the vault being the cover of a square module and supported by point and non-directional supports, thus creating a fluid and open space.

He used the alternative of using the slopes to hide the facades and integrate the landscape: Cruylles house (1967) on the Costa Brava.

The urban planning of Bonet pursued systematisation in the combination of units and the resolution of circulations and accesses. In this way, he organised streets on different levels for distribution to the houses. To provide greater character to each housing unit, it endowed them with their vitality, and thus they acquired independence: the TOSA housing complex (1945) and the project for the yellow house (1943). He was also concerned about the separation of automobile and pedestrian circulation: in Punta Ballena, light bridges crossed the streets looking for the sea.

The concept of series production, so deeply rooted by the ideologues of the modern movement, evokes precision in modulation and in the creation of repeatable and combinable spatial units: Rubio house pyramids in the Mar Menor (1965). But for Bonet, this aspect does not lead to repetition and fanaticism but to creating coherent fields. Bonet designed furniture in its entirety: closing pieces, coverings, and everything that participated in his sought-after architectural unit.

He sought simplicity of lines for his projects. This purist trend can be seen in the Oaks house or the flat Glass Pavilion of 1958, on the side façade of the Palace Terrace, or in some interior spaces where a few strokes define everything.

He strove to introduce the values of surrealism to the rationalist framework, with a greater concern for individual psychology. He showed great interest in establishing integration with the landscape and with the traditions of localities. He introduced freedom of form without abandoning functionalist character.

ENQUIRE ABOUT THE DESIGNER