Side Gallery

Side Gallery

WishlistFollow

MARIA GARCÍA & OTHERS

NEW YORK, 2019

Publisher: MOMA

Edited By: Maria García and others

Building: Hardback

Dimensions: 24.13 x 2.54 x 27.94 cm

Language: English

Pages: 240

Sur moderno: Journeys of Abstraction explores the abstract and concrete art movements that thrived in Latin America between the mid-1940s and the late 1970s in the context of the profound cultural transformations that gave rise to them. Published in conjunction with an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Sur moderno features work by artists from Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil and Venezuela―including Lidy Prati, Tomás Maldonado, Rhod Rothfuss, Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica, Jesús Rafael Soto and Alejandro Otero―who advanced the achievements of early-20th-century geometric abstraction and built a new modern vision of the continent. This splendidly illustrated book highlights a selection of works gifted to MoMA by Patricia Phelps de Cisneros between 1997 and 2016―a donation that has had a transformative impact on the Museum’s holdings of Latin American art. The Cisneros Modern Collection, which includes paintings, sculptures and works on paper, allows for an in-depth study of the art produced in the region during the middle of the century, enabling the Museum to represent a more wide-ranging, narrative of artistic practices and to demonstrate the important impact South America has had on modern art.

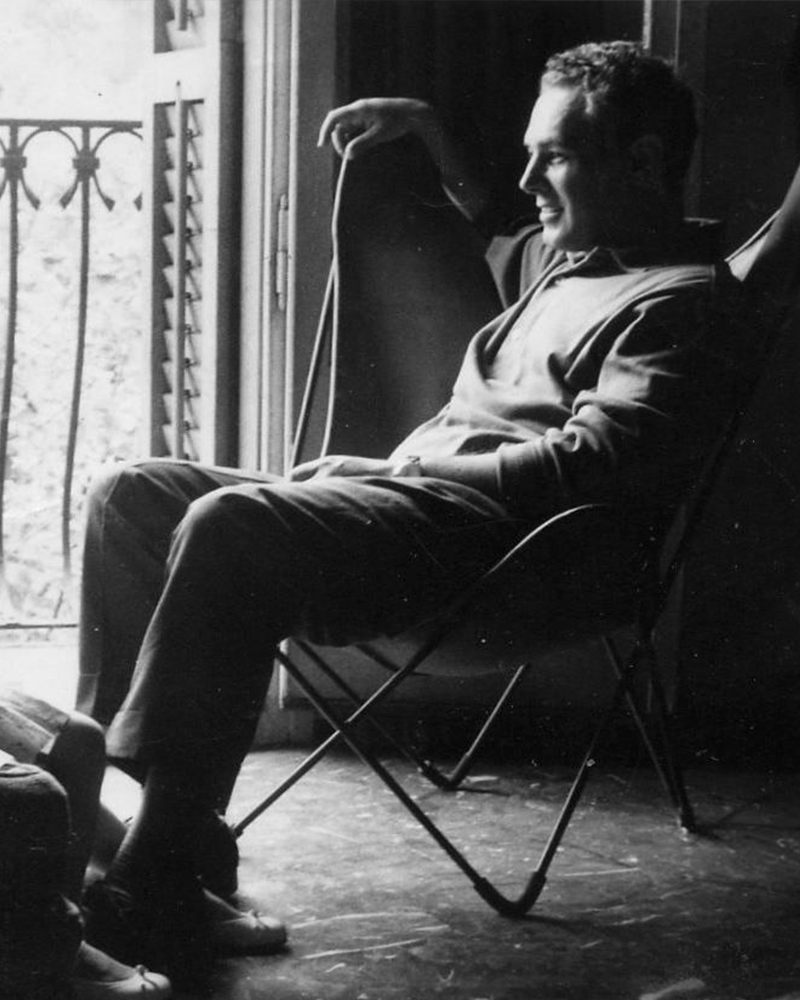

Antonio Bonet Castellana, born in Barcelona on August 13th, 1913, and died in Ibídem on September 12th, 1989, was a Catalan architect, urban planner, designer, and resident of Río de la Plata (Argentina) for the best part of his life.

Bonet was trained in two ways: on the one hand, from the teaching he received at University, and on the other, from the working relationship, he formed with J. Lluis Sert, who was involved in the Modernist Movement leads to the formation in 1930 of the GATPAC.

In 1935, he became a collaborator in Catalonian architects Jose Luis Sert and Torres Clavé and a member of the GATPAC until 1935. During this period, Bonet worked on the Roca jewelry projects, the houses in Garraf, the kindergarten, and the MIDVA stand, for which he was awarded first prize at the Barcelona Decorators Show. In 1933 he attended the historic cruise aboard the Patris II, which took him to Athens, where he participated in drafting the Athens Charter, a key event for the architectural culture of the 20th century. During the lecture, the functions of living, working, resting, and circulating were enunciated as the fundamental elements of urban development. On this same trip he met Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto.

In 1936, as soon as he finished his architectural studies, he traveled to Paris to join Le Corbusier's studio. In Le Corbusier's studio, he projected the house made by Bonet at the request of the master: the Maison Jaoul. He also designed the main building for the Liege International Exposition, the Water Pavilion. For this work, he incorporated surrealist ideas into the functionalist architecture of the moment, one of the aspects that would later characterise his work.

In 1937 at the International Exposition in Paris, Le Corbusier presented the Pavilion Des Temps Nouveaux. Bonet collaborated with Sert to realise the Spanish Pavilion, whose symbolic character was fundamental, attending to the concept of unity sought at that historical moment. This construction linked the different works of Spanish artists on display (Miró, Calder, and Picasso), integrating them into architecture.

During his tenure at Le Corbusier's studio, he met two young Argentine architects: Juan Kurchan and Jorge Ferrari Hardoy. The prospect of war on the horizon, coupled with his new friendships, led Bonet to move to Argentina in 1938. Once there, he formed, together with Kurchai and Jorge Ferrari, the Austral Group, which acted as the first reference to modern Argentine architecture and was in charge of spreading the basic ideas of the modernist movement and offering profound criticism. He set out to study the country's urban planning problems and suggest solutions.

In June 1939, they published the Group's manifesto under the title Will and Action. They defended the superimposition of some values of surrealism to the rationalist training of architects and incorporated the individual's psychological needs into the strict functionalism of the modern movement. This manifesto exposes Bonet's stance towards architecture and his effort to establish continuity with each area's landscape, techniques, and materials.

Together with his partners, he is credited with the legendary BKF chair, although its authorship is finally assigned to Jorge Ferrari Hardoy.

Antonio Bonet built between 1938 and 1939 what is considered the first modern construction in Buenos Aires, a residential building on Paraguay and Siupacha streets. Later he built buildings such as the OKS house in Martínez (1954-1958) or the Rivadavia tower in Mar del Plata (1956). During the 1940s, he settled in Uruguay, where he worked on the urban project for Punta Ballena, Maldonado, and built the hotel restaurant La Solana del mar (1947), the La Gallarda house for the poet Rafael Alberti, and the Berlingieri house ( 1946), where Catalan vaults extend the dunes of the landscape. In these creations, freedom of form, an emblematic characteristic of Bonet, is present without abandoning his rationalist background.

Back in Argentina in 1950, he met again with the mechanisms of the defunct Austral Group to participate in the drafting of the Buenos Aires Plan. Antonio Bonet was undoubtedly one of the definitive links to European avant-garde architecture in Latin American architects.

In theory, he considered architecture as a matter of order in human life and believed that the architect's activity extended from the conception of a piece of furniture to the planning of a city. One constant was the effort to integrate the varying scales of the human habitat, investigating new materials and forms to achieve architectural spaces and furniture that would be at the service of society.

It is necessary to emphasize Bonet's importance to the dynamics of space; It creates different perceptual sensations when playing with changes in scale, the various definitions that light produces through the closing, and the movement of floors and ceilings. Bonet designed from a general approach, which allowed him to see the intention of the work, through the patios, terraces, and galleries, to the architectural elements such as cornices, railings, or closings.

Bonet was sympathetic to suggestive and imaginative environments manifested in formal resolutions and the approach to spatial situations. For example, the feeling of abnormality created by the support of heavy structures by columns that give the impression of being diluted: Casa Oks (1955), La Ricarda (1953), and Castanera (1964). He also used the pressure of heavy concrete structures supported at low heights, such as in the Terraza Palace building (1957), the Silver Sea, or the Torre del Barrio Pedralpes in Barcelona (1973).

On his return to Spain, he followed this trend: he designed sculptural towers, such as the Cervantes (1955) or the Urquinaona Tower (1971), the most significant within this line, the project for Plaza de Castilla, Madrid (1964) and the Torre Rosas (1967).

His connection with the Mediterranean spirit manifested in the choice of materials and the vision of his buildings. The public and private borders were raised, blurring their limits and resulting in a new relationship. They were characteristic of his work of intermediate climates. He joined these two conclusions in the vaults to cover spaces uniting the traditional techniques and materials of the place. Some examples are: houses in Martínez (1940), Berlingieri's home (1947), a work in which it is easy to see Mediterranean influence; in this case, the vaults define a bearing and spatial direction, unlike in the La Ricarda (1953) made on his return to Spain, where the concept evolves with the vault being the cover of a square module and supported by point and non-directional supports, thus creating a fluid and open space.

He used the alternative of using the slopes to hide the facades and integrate the landscape: Cruylles house (1967) on the Costa Brava.

The urban planning of Bonet pursued systematisation in the combination of units and the resolution of circulations and accesses. In this way, he organised streets on different levels for distribution to the houses. To provide greater character to each housing unit, it endowed them with their vitality, and thus they acquired independence: the TOSA housing complex (1945) and the project for the yellow house (1943). He was also concerned about the separation of automobile and pedestrian circulation: in Punta Ballena, light bridges crossed the streets looking for the sea.

The concept of series production, so deeply rooted by the ideologues of the modern movement, evokes precision in modulation and in the creation of repeatable and combinable spatial units: Rubio house pyramids in the Mar Menor (1965). But for Bonet, this aspect does not lead to repetition and fanaticism but to creating coherent fields. Bonet designed furniture in its entirety: closing pieces, coverings, and everything that participated in his sought-after architectural unit.

He sought simplicity of lines for his projects. This purist trend can be seen in the Oaks house or the flat Glass Pavilion of 1958, on the side façade of the Palace Terrace, or in some interior spaces where a few strokes define everything.

He strove to introduce the values of surrealism to the rationalist framework, with a greater concern for individual psychology. He showed great interest in establishing integration with the landscape and with the traditions of localities. He introduced freedom of form without abandoning functionalist character.

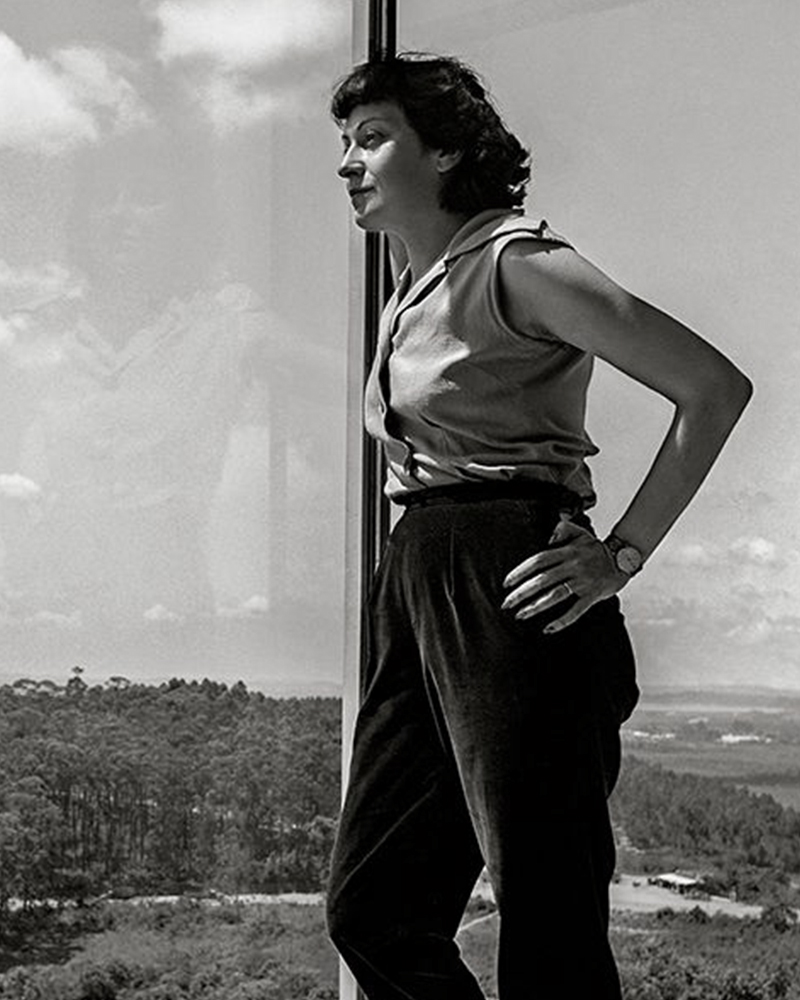

Achillina Bo, best know as Lina Bo Bardi, (born December 5, 1914, Rome, Italy—died March 29, 1992, São Paulo, Brazil), was an Italian-born Brazilian Modernist architect, industrial designer, historic preservationist, journalist, and activist whose work broke free from convention. She designed daring, distinctive structures that merged Modernism with populism.

Bo Bardi graduated with an architecture degree in 1939 at the University of Rome, where she had studied under architects such as Marcello Piacentini and Gustavo Giovannoni. Upon graduating, Bo Bardi moved to Milan and began working with the architect Carlo Pagani as a design journalist. She also worked with the famous architect and designer Gio Ponti and collaborated with him on the magazine Lo Stile, while contributing to several other Italian design publications. In 1944 she became deputy director of Domus, the acclaimed design magazine established by Gio Ponti in 1928, and retained the post until 1945. In 1945 Domus commissioned Bo Bardi, Pagani, and photographer Federico Patellani to travel through Italy documenting the destruction of World War II. Later that year, she collaborated with Pagani and art critic Bruno Zevi on the short-lived magazine A – Attualità, Architettura, Abitazione, Arte, which published their judgments and verdicts discussed ideas for restoration of the postwar devastation.

Pietro Maria Bardi, an art gallery director, dealer, and critic, became her husband in 1946. Pietro was soon invited to Brazil by the media tycoon Assis Chateaubriand to help coordinate the Art Museum of São Paulo (Museu de Arte de São Paulo; MASP). The couple, as a result, emigrated across the Atlantic to the modernist hotspot Sao Paulo.

Bo Bardi designed the interior and the museum fittings for the first iteration of MASP, which opened in 1947. She developed an innovative system for suspending paintings away from the wall. (Her design was torn down in the 1990s and replaced with a conventional wall hanging system.) She also designed folding stackable chairs made from Brazilian jacaranda wood and leather intended for use at lectures and museum events. Later in life, she curated an exhibition at the museum on the history of chair design.

In 1950 Bo Bardi founded the magazine Habitat with her husband and worked as the editor until 1953. During that time, it was the most influential architectural magazine in Brazil. She became a citizen of Brazil (1951) and started the country's first industrial design course at the Institute of Contemporary Art (a part of the expanded MASP). She designed for her and her husband, the notorious Modernist Le Corbusier, influenced Casa de Vidro (Glass House) in the Morumbi neighborhood of São Paulo. Constructed on a hill, Casa de Vidro, over time, integrated into the landscape entirely. The front of the house extended out over the slope of the hill, elevated and supported on delicate-looking stilts. In 1951 she also designed her most famous piece of furniture, Bardi's Bowl, a chair in the form of an adjustable hemispherical bowl resting in a steel cradle.

By the mid-1950s, it was clear that MASP had outgrown its original building, with galleries and dedicated spaces for teaching art. By the 1950s, the popularity of MASP overcame the museum's physical capacity. In 1958 Bo Bardi was commissioned to design the new building. The building stands today as her most dominant creation. Located on São Paulo's Paulista Avenue, Bo Bardi's iconic glass-and-concrete building was elevated 8 meters (26.2 feet) above the ground on sizeable red pillars. The space at ground level provides a shaded heaven away from the hot summer sun and a gathering place for concerts, protests, and socializing.

In the late 1950s Bo Bardi began an extended period of living and working in Salvador, a poor city rich in cultural heritage in the northeastern state of Bahia. She gave several lectures at Bahia University's School of Fine Arts in 1958, and in 1959 she was invited to create and run Bahia's Museum of Modern Art (Museu de Arte Moderna da Bahia). She chose to house the museum in the Solar do Unhão, a former salt mill and part of a network of historic seaside constructions that she restored in 1963. Bo Bardi added a museum of popular art and an art school to the Museum of Modern Art, all under the roof of Unhão.

However, political unrest forced Bo Bardi to leave Bahia in 1964. Her return to São Paulo marked the beginning of Brazil's lengthy era of oppression under a military dictatorship that lasted until 1985. During that period, Bo Bardi curated exhibitions and worked in theatre, designing sets and costumes for several productions, notably a 1969 production of Im Dickicht der Städte (In the Jungle of Cities), an early play by Bertolt Brecht.

Bo Bardi's time in Bahia altered her political and aesthetic philosophies. The region's language and historic architecture led her to adopt a design process guided by social and ethical responsibility and inspired by allegiance to her adopted country and its native aesthetic traditions. Bo Bardi dedicated herself to creating only Brazilian architecture, projecting simple designs, and sourcing local materials, the style of architecture she called "Arquitetura Povera" ("poor", or, "simple" architecture). Since her initial experience in Salvador, much of her work involved re-designing and developing existing structures and restoring and preserving historic buildings. Throughout the 1980s Bo Bardi led preservation and restoration projects in the historic center of Salvador, including the House of Benin, which houses an art collection, as well as Misericórdia Hill, an extremely steep historic street (both in 1987). Her next major architecture project was the SESC Pompéia (built in stages, 1977–1986), a leisure and cultural center in São Paulo sponsored by the nonprofit Social Service of Commerce (Serviço Social do Comércio). Bo Bardi converted an old steel drum factory into a center for various facilities; sports, theatre, and other leisure activities.

Bo Bardi, although late, has been given her due as one of the most prolific women architects of the 20th century. In the mid-1980s, working alongside the architects André Vainer and Marcelo Carvalho Ferraz, Bo Bardi designed an addition to the Glass House, the Instituto Lina Bo e P.M Bardi (originally the Instituo Quadrante). As well as housing Bo Bardi's archive, The Instituto Lina Bo e P.M Bardi is an exhibition space dedicated to the study of Brazilian art and architecture.

In 2012, the centennial of her birth, Bo Bardi's career was celebrated with the launch of a limited-edition line of her bowl chair, a major traveling retrospective organized by the British Council in London, and the publication of a scholarly monograph discloses her life's work.

Cornelis Zitman was born in 1926 into a family of builders. At the age of 15, he started studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in The Hague. His studies terminated in 1947; he then refused to enroll in the required military service objecting to the Dutch political activities in Indonesia and thus left the country aboard a Swedish oil tanker that would take him to Venezuela.

He settled in the city of Coro, where he found employment as a technical draftsman in a construction company. He began to paint in his free time and make his first forays into the field of sculpture. Two years later, he moved to Caracas, where he worked as a furniture designer for a factory of which he would later become the director. In the early 1950s, Zitman, in partnership with the engineer Antonio Carbonell went on to create Tecoteca, his furniture manufacturing company. The exceptional curation of what Cornelis J. Zitman produced in the years he designed and manufactured furniture offered an insight into the manufacturing of modern furniture in Venezuela, which is still very much being discovered and rests on the shelf of the things that hope to be better understood and settled in the country's recent history. There is nothing but tremendous praise for the designer; his work is now reconnecting with the public, the audience for whom it was originally designed.

The life of Tecoteca itself was relatively short-lived, not due to the shortcomings of the furniture but to a series of unfortunate events and the social and political situation. Four years after its creation, Tecoteca went from one crisis to another. In 1956, his workshop in Boleíta caught fire. Although the project for its reconstruction and relaunch in Cagua had been programmed and carefully studied with the acquisition of machinery and the establishment of procedures of the latest technological ability, the business bankruptcy occurred admits a tidal wave of the economic and political changes in 1958, which proved unpredictable and unrecoverable. The name Tecoteca was liquidated along with its assets and acquired as a brand for the production of kitchen furniture. Today it survives as the name of a building located on Avenida Francisco de Miranda, south of the Atlantic building, in Los Palos Grandes, near where in its heyday Tecoteca had its most impressive store.

A mixture of admiration and disbelief is the feeling that best accompanies the life of Tecoteca. It was an era of splendor and misery. The portfolio of forms and functions furnished the Monserrat residential building in Altamira, the work of Emile Vestuti when he worked at the firm of architects Guinand and Benacerraf, and the renowned Club Táchira de Fruto Vivas, through a concerted program, focused on the production of standardized furniture for oil camps for Shell company in Venezuela, which Zitman conceived with managerial logic and quality.

Good quality and economical furniture was what Zitman had became known for, and it was a reputation he maintained within the Venezuelan school of design. Jorge F. Rivas Pérez describes and focuses Zitman's activity as The Decade of Design / 1947-1957: a crucial chapter in the production of conceived and manufactured furniture in Venezuela. After the company's closure, Zitman decided to give up his entrepreneurial life and moved to the island of Grenada, where he devoted himself entirely to painting and began to assert his character as a sculptor.

In 1961 he traveled to Boston in the United States to participate in an exhibition of painting and design. That same year he returned to Holland with the desire to study casting techniques. In 1964 he worked as an apprentice in the foundry of the sculptor Pieter Starreveld and then returned permanently to Venezuela. On his return, he was hired by the Central University as a professor of design. The following year he began to work more intensively on small-format sculpture modeled directly in wax. In 1971 he exhibited for the first time at the Galerie Dina Vierny in Paris, and from then on, he devoted himself exclusively to sculpture. During these years he held several individual exhibitions in Venezuela, France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, the United States, Japan, and other countries. He won several national and international awards.

Zitman participated in several international exhibitions such as the Budapest Sculpture Biennial and the São Paulo Biennial, the FIAC in Paris, and the ARCO fair in Madrid. His solo exhibitions include the Galerie Dina Vierny in Paris, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Caracas, the Tokoro Gallery in Tokyo, the Museum of Modern Art in Bogotá, and the Beelden Zee Museum in Scheveningen, the Netherlands. His sculptures seek to reproduce and exaggerate the morphology of the indigenous people of Venezuela, especially the female figure. His works are in private collections and museums in various countries, such as the National Art Gallery of Caracas and the Museum of Contemporary Art of Caracas in Venezuela, and the Musée Maillol in Paris.