Side Gallery

Side Gallery

WishlistFollow

ARIC CHEN AND ZESTY MEYERS

NEW YORK, 2016

Edited By: The Monacelli Press

Building: Hardback

Language: English

Pages: 304

Twentieth-century Brazilian furniture design is perhaps the last great largely unknown tradition of modernism. The furniture is characterized by rich and textured hardwoods it illustrates a resourcefulness and simplicity that exemplify the national character. With over 400 images and including new photography, Brazil Modern: The Rediscovery of Twentieth-Century Brazilian Furniture explores the history and legacy of this innovative design tradition. Featuring the work of —Lina Bo Bardi, Oscar Niemeyer, Joaquim Tenreiro, and Sergio Rodrigues—as well as numerous designers whose work and reputations only recently reached foreign shores, Brazil Modern is the first complete guide to this undiscovered modern design.

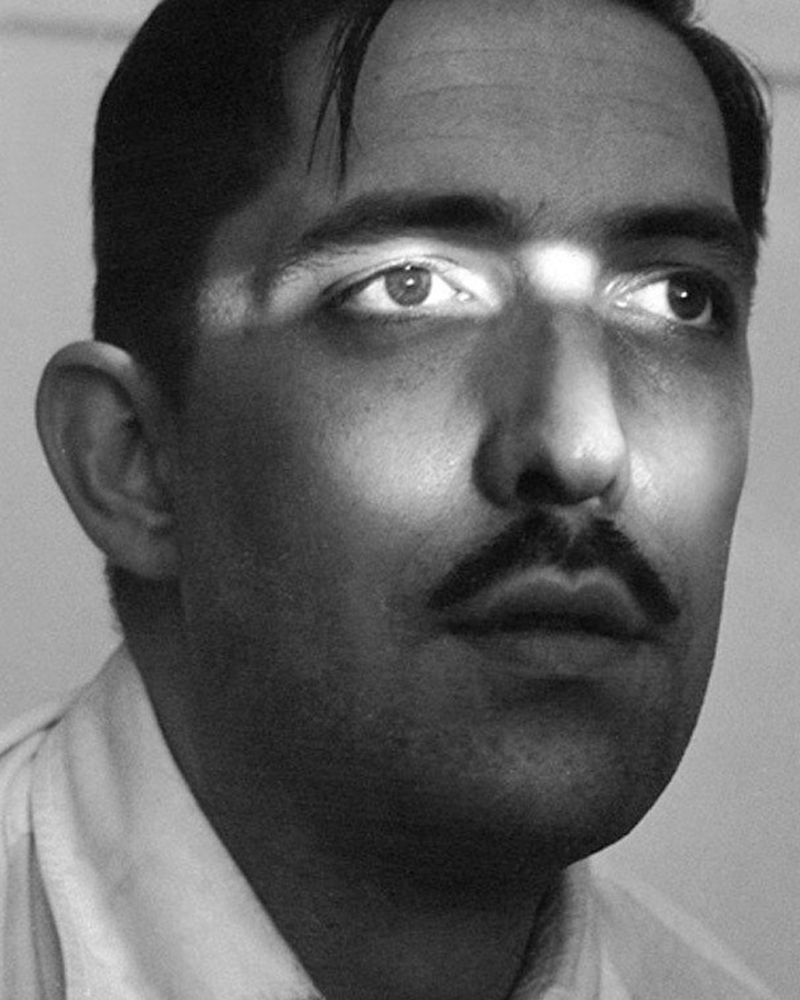

Geraldo de Barros (Chavantes 27th February 1923 - Sao Paulo 17th April 1998) was a prolific artist across various media. He experimented relentlessly with utopian ideals, divulged through his exploration of furniture design from the mid-1950s till the late 1980s. While undoubtedly Brazilian, he drew much of his aesthetic influences from European avant-garde culture, from De Stijl and Bauhaus to Gestalt psychology.

Starting his artistic career in painting, he then found himself in photography; de Barros held a successful exhibition "Fotoformas" in 1950, the title being a reference to Gestalt. His artistic trajectory put him at the forefront of experimental photography, and in 1951 he was awarded a scholarship from the French government, which allowed him to travel and study in France. While in Europe, he also traveled to Zurich, where he met Max Bill, a former Bauhaus graduate who was collaborating at the time with the Scholl Foundation on the creation of a new design institute that had the ambition to continue the Bauhaus traditions with the integration of the human and technical element in design teaching and practice. Max Bill invited Geraldo to visit the institute (not officially opened till 1953) in Ulm, Germany, where he consequently spent some weeks attending workshops and was subsequently heavily influenced by what would be Max Bill's idea of Gute Form. The essence of Gute Form was the belief that objects, if carefully designed, can bring art into everybody's home, and art can be a way not only to reflect on the world but to make visible connections and abstractions without using verbal language. Here we can see a clear link between Geraldo's future ideals for furniture design and Bill's philosophy.

After his return to Sao Paulo and following further success as an artist, a change of government was to change Brazil. A new wave of investments from Europe was inaugurated by the president with the motto 'fifty years in five.' Modernization and industrialisation were being imposed from above. Geraldo de Barros, along with a Dominican Priest, Friar João Batista Pereira dos Santos, embarked on his first and most crucial venture as a furniture designer. In 1954 Unilabor was created and became a mechanism of modernization from below.

Unilabor was unity in work and a unity through work. The workers ran a self-managed e factory; it was a system of production that aimed to unify not only form and function but also a living community and production processes. This balance of forces certainly informed the discreet beauty of Unilabor furniture pieces. The tension that affected the products of the national wave of industrialization is clearly absent from the relaxed, warm lines of these pieces. In its context, Unilabor, in fact, quickly became a social model. It was a working environment that was perceived as healthy. It was created to be less a company, more a community.

The other two founding members of Unilabor, the engineer Justino Cardoso and the toolmaker Antônio Thereza provided specialist knowledge and skills while Geraldo de Barros made the drawings. Geraldo's approach to design was very humanistic. He intended to socialise art and its messages. By using the products, he designed for their daily activities, owners of Unilabor furniture were using art. For Geraldo, the designer's role consisted in mediating between society and industry, aiming to solve the tension between quantity and quality. João Batista and Geraldo agreed that if market trends ruled manufacturing, it eventually became informed by quantitative interests only, with a disadvantageous effect on the quality of the product and the working and living conditions of the workmen. Despite its ideals, Unilabor eventually ran into economic difficulties and eventually only lasted thirteen years.

Geraldo then dedicated himself to the furniture factory he created in 1964 with a former Unilabor cabinet-maker, Aloísio Bione. Rather than being a company with a clear aesthetics, as many Italian furniture manufacturers of the nineteen-sixties, to which it can be compared, Hobjeto Indústria e Comércio de Móveis was characterised by extreme flexibility of the form, which stays constant throughout the several lines of products Geraldo de Barros designed over the years. The furniture was also progressive, evolving to follow the dominant shapes of the time: more angular and squarer when the furniture was more geometric; more rounded when the products had softer lines; and finally made of long, continuous lines when Hobjeto introduced a furniture family made with tubular elements.

Both in the case of Unilabor and Hobjeto, interestingly, the essential component of Geraldo's design philosophy is the chair. This is particularly fascinating, especially if we consider that at the time, modular systems were prevalent amongst most industrial designers. While armchairs inspire intimacy and solitude, chairs, like sofas, have a significant social aspect. The proportions of Geraldo's chairs multiply into larger furniture items, and the environments arranged for publicity photographs are often constructed around the chair's presence.

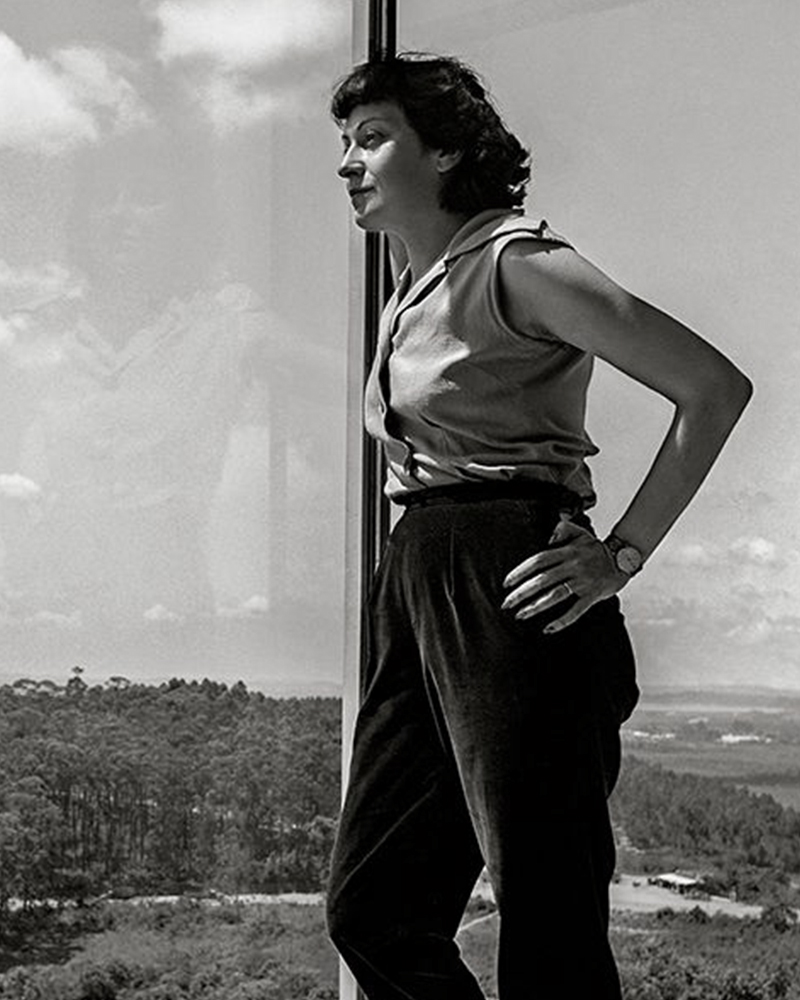

Achillina Bo, best know as Lina Bo Bardi, (born December 5, 1914, Rome, Italy—died March 29, 1992, São Paulo, Brazil), was an Italian-born Brazilian Modernist architect, industrial designer, historic preservationist, journalist, and activist whose work broke free from convention. She designed daring, distinctive structures that merged Modernism with populism.

Bo Bardi graduated with an architecture degree in 1939 at the University of Rome, where she had studied under architects such as Marcello Piacentini and Gustavo Giovannoni. Upon graduating, Bo Bardi moved to Milan and began working with the architect Carlo Pagani as a design journalist. She also worked with the famous architect and designer Gio Ponti and collaborated with him on the magazine Lo Stile, while contributing to several other Italian design publications. In 1944 she became deputy director of Domus, the acclaimed design magazine established by Gio Ponti in 1928, and retained the post until 1945. In 1945 Domus commissioned Bo Bardi, Pagani, and photographer Federico Patellani to travel through Italy documenting the destruction of World War II. Later that year, she collaborated with Pagani and art critic Bruno Zevi on the short-lived magazine A – Attualità, Architettura, Abitazione, Arte, which published their judgments and verdicts discussed ideas for restoration of the postwar devastation.

Pietro Maria Bardi, an art gallery director, dealer, and critic, became her husband in 1946. Pietro was soon invited to Brazil by the media tycoon Assis Chateaubriand to help coordinate the Art Museum of São Paulo (Museu de Arte de São Paulo; MASP). The couple, as a result, emigrated across the Atlantic to the modernist hotspot Sao Paulo.

Bo Bardi designed the interior and the museum fittings for the first iteration of MASP, which opened in 1947. She developed an innovative system for suspending paintings away from the wall. (Her design was torn down in the 1990s and replaced with a conventional wall hanging system.) She also designed folding stackable chairs made from Brazilian jacaranda wood and leather intended for use at lectures and museum events. Later in life, she curated an exhibition at the museum on the history of chair design.

In 1950 Bo Bardi founded the magazine Habitat with her husband and worked as the editor until 1953. During that time, it was the most influential architectural magazine in Brazil. She became a citizen of Brazil (1951) and started the country's first industrial design course at the Institute of Contemporary Art (a part of the expanded MASP). She designed for her and her husband, the notorious Modernist Le Corbusier, influenced Casa de Vidro (Glass House) in the Morumbi neighborhood of São Paulo. Constructed on a hill, Casa de Vidro, over time, integrated into the landscape entirely. The front of the house extended out over the slope of the hill, elevated and supported on delicate-looking stilts. In 1951 she also designed her most famous piece of furniture, Bardi's Bowl, a chair in the form of an adjustable hemispherical bowl resting in a steel cradle.

By the mid-1950s, it was clear that MASP had outgrown its original building, with galleries and dedicated spaces for teaching art. By the 1950s, the popularity of MASP overcame the museum's physical capacity. In 1958 Bo Bardi was commissioned to design the new building. The building stands today as her most dominant creation. Located on São Paulo's Paulista Avenue, Bo Bardi's iconic glass-and-concrete building was elevated 8 meters (26.2 feet) above the ground on sizeable red pillars. The space at ground level provides a shaded heaven away from the hot summer sun and a gathering place for concerts, protests, and socializing.

In the late 1950s Bo Bardi began an extended period of living and working in Salvador, a poor city rich in cultural heritage in the northeastern state of Bahia. She gave several lectures at Bahia University's School of Fine Arts in 1958, and in 1959 she was invited to create and run Bahia's Museum of Modern Art (Museu de Arte Moderna da Bahia). She chose to house the museum in the Solar do Unhão, a former salt mill and part of a network of historic seaside constructions that she restored in 1963. Bo Bardi added a museum of popular art and an art school to the Museum of Modern Art, all under the roof of Unhão.

However, political unrest forced Bo Bardi to leave Bahia in 1964. Her return to São Paulo marked the beginning of Brazil's lengthy era of oppression under a military dictatorship that lasted until 1985. During that period, Bo Bardi curated exhibitions and worked in theatre, designing sets and costumes for several productions, notably a 1969 production of Im Dickicht der Städte (In the Jungle of Cities), an early play by Bertolt Brecht.

Bo Bardi's time in Bahia altered her political and aesthetic philosophies. The region's language and historic architecture led her to adopt a design process guided by social and ethical responsibility and inspired by allegiance to her adopted country and its native aesthetic traditions. Bo Bardi dedicated herself to creating only Brazilian architecture, projecting simple designs, and sourcing local materials, the style of architecture she called "Arquitetura Povera" ("poor", or, "simple" architecture). Since her initial experience in Salvador, much of her work involved re-designing and developing existing structures and restoring and preserving historic buildings. Throughout the 1980s Bo Bardi led preservation and restoration projects in the historic center of Salvador, including the House of Benin, which houses an art collection, as well as Misericórdia Hill, an extremely steep historic street (both in 1987). Her next major architecture project was the SESC Pompéia (built in stages, 1977–1986), a leisure and cultural center in São Paulo sponsored by the nonprofit Social Service of Commerce (Serviço Social do Comércio). Bo Bardi converted an old steel drum factory into a center for various facilities; sports, theatre, and other leisure activities.

Bo Bardi, although late, has been given her due as one of the most prolific women architects of the 20th century. In the mid-1980s, working alongside the architects André Vainer and Marcelo Carvalho Ferraz, Bo Bardi designed an addition to the Glass House, the Instituto Lina Bo e P.M Bardi (originally the Instituo Quadrante). As well as housing Bo Bardi's archive, The Instituto Lina Bo e P.M Bardi is an exhibition space dedicated to the study of Brazilian art and architecture.

In 2012, the centennial of her birth, Bo Bardi's career was celebrated with the launch of a limited-edition line of her bowl chair, a major traveling retrospective organized by the British Council in London, and the publication of a scholarly monograph discloses her life's work.

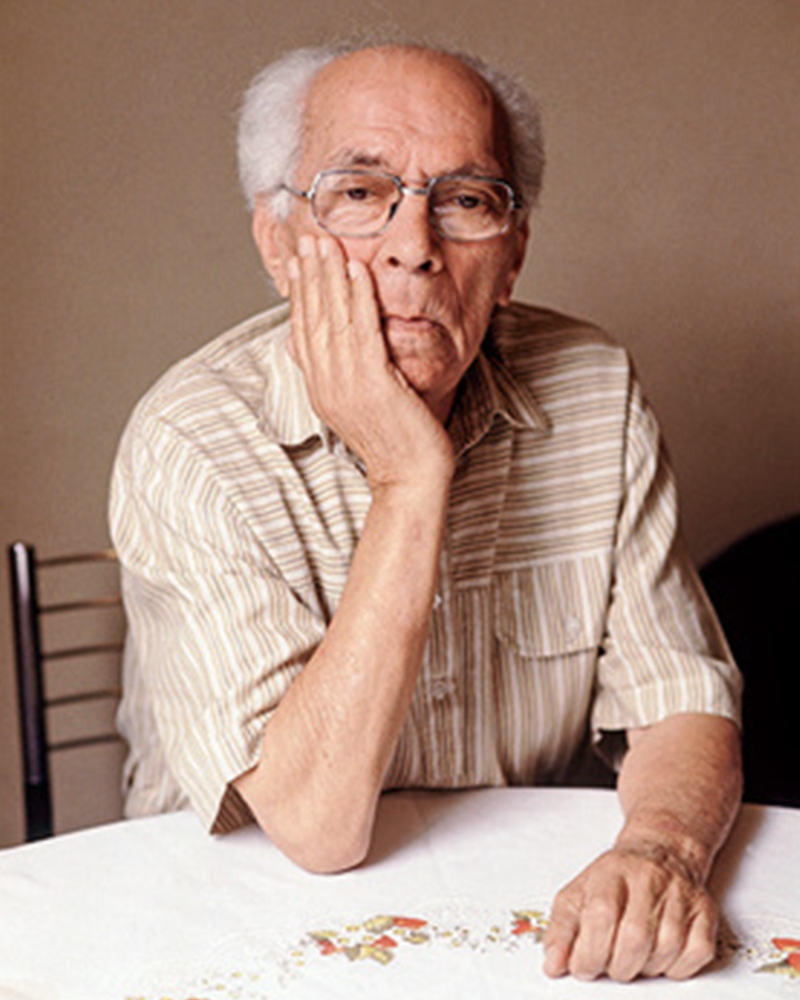

Joaquim Tenreiro (Melo Guarda, Portugal 1906 - Itapira Sao Paulo 1992) was a, sculptor, painter, engraver and designer. Born into a family of joiners, at the age of two, his family emigrated to Brazil, settling in Niterói, Rio de Janeiro. In 1914 he returned to Portugal. He helped his father with woodwork projects and began painting classes. He returned to live in Brazil between 1925 and 1927. In 1928, he moved to Rio de Janeiro permanently. He studied drawing at the Portuguese Literary Lyceum and enrolled in the Liceu de Artes e Ofícios. In 1931, he joined the Bernardelli Nucleus, a group created in opposition to the academic teaching of the National School of Fine Arts - Enba.

After some years of dabbling in as a painter, Joaquim traversed his talents and went back to wood, "I stuck with painting up to a point, but gave it up because I could not stay away from the wood-working shop...what kept me going was furniture" (Soraia Cals, Tenreiro, Rio de Janeiro, 1998, p. 190). He designed for Laubish & Hirth, Leandro Martins, and Francisco Gomes, specializing in French, Italian, and Portuguese furniture. A decade later, he founded Langenbach & Tenreiro, which would become renowned for its modern furniture designs. Tenreiro's partner insisted on selling traditional furniture, while Tenreiro argued for a modern sensibility. In the early years, Tenreiro designed both conservative and modern furniture for their inventory. However, by the late 1940s, the modern movement had taken hold in Brazil, and when only Tenreiro's original pieces sold, the shop dedicated itself solely to contemporary designs.

His success as a designer commenced in 1942 when he was commissioned to design and manufacture the furniture for the residence of Francisco Inácio Peixoto, in Cataguases, in the interior of Minas Gerais. The residence was designed by architect Oscar Niemeyer (1907 - 2012), to whose work Joaquim identified beautifully, creating the commissioned pieces in assimilation with the purity of Niemeyer's architectural forms. The furniture Tenreiro designed for this project were the first pieces made by him in which it is possible to distinguish the sober beauty of form and the wise use of Brazilian wood so identifiable in his works throughout the next two decades.

The Light Armchair (ca.1942), made in ivory wood, with a darker version in imbuia, was upholstered in fabric stamped by Fayga Ostrower (1920 - 2001) and one of his most famous pieces. The chair was conceived according to his principle that Brazilian furniture should be light; in Tenreiro's words, lightness has nothing to do with the weight itself but with grace and functionality. Testimony to the ideological alignment of modern Brazilian furniture, Tenreiro's design is rooted in the principle of stripping back the unnecessary to demonstrate the true beauty of an object while maintaining the utmost function.

His acclaimed Three-legged Chair (ca.1947) associates geometry with colour through the particular use of Brazilian woods. It is chromatically innovative composed of a combination of timbers (imbuia, roxinho, rosewood, ivory, and cabreúva), all with varying shades. Tenreiro spoke of the technical difficulties in creating these chairs—of combining woods that retain different levels of humidity, dry at varying rates, and expand and shrink differently—but the design's success speaks to his technical prowess and to his artistic vision. Like other Tenreiro furniture of this period, it has a light and luminous appearance, contrasting with the solid and sober furniture he previously created for Laubisch & Hirth.

In some chairs and armchairs, Joaquim explored weaving natural materials such as straw that evoke indigenous braiding and basketry. The use of wood and natural fibers is generally associated with adapting furniture to a tropical climate; together with these organic compositions, other works of Tenreiro's, such as the Structural Chair, present straight lines, and geometric elements, creating structures from both wood (1957) and metal (1961). Tenreiro's deep knowledge of wood is illustrated through the poetic features in his works.

At the end of the 1960s, he closed his stores and stopped manufacturing furniture for personal and market reasons. Instead, he returned to the realms of painting and dedicated himself to sculpture. Techniques discovered during his design days can be seen in his sculptures. For example, the chromatic composition of woods he employed in the Three-Foot Chair was later resumed in some sculptural reliefs, in which the artist explores the differences in color, textures, and the veins of wood; his work Circles (1979) demonstrated this.

Tenreiro's productions are renowned for their combination of modern characteristics that define mid-century Brazilian furniture, such as simplicity, the use of local materials, function, and artistic beauty.

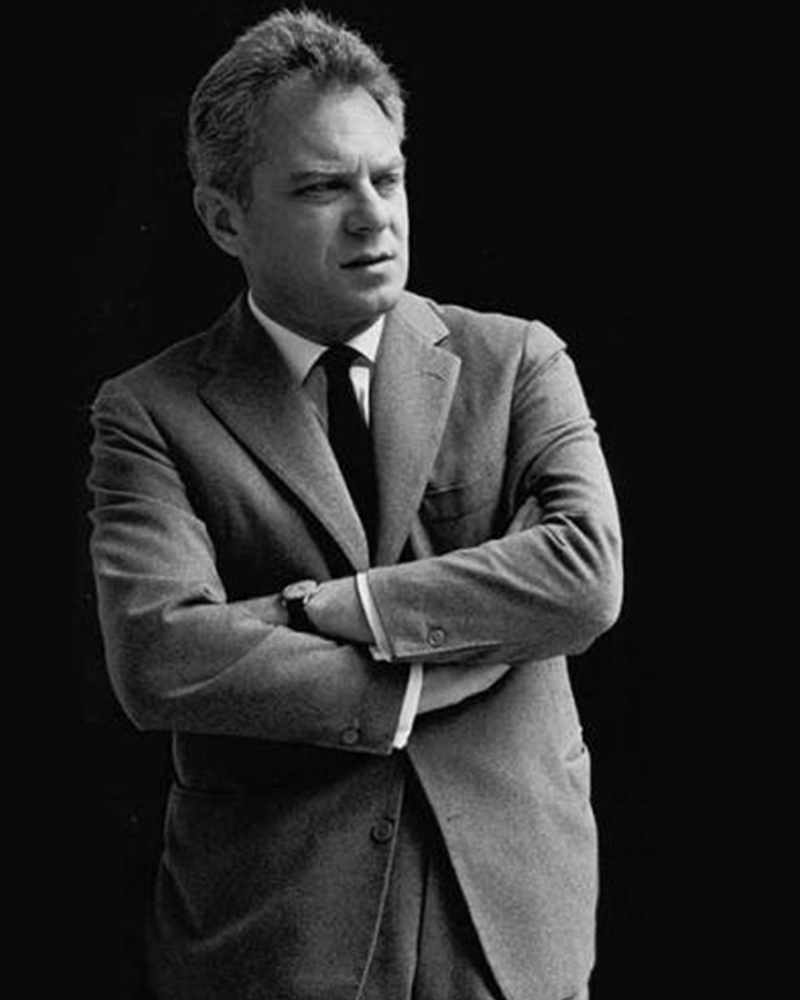

Jorge Zalszupin (b.Warsaw, Poland 1922 - d.São Paulo, Brasil 2020) graduated as an architect in Romania in 1945. His importance in Brazilian design is not yet fully documented. Besides owning the L'Atelier furniture factory, dedicated to modern furniture design, Zalszupin led a unique initiative: he coordinated a team of designers who worked for four different factories owned by the same business group, the Forsa group.

Zalszupin immigrated to Brazil in 1949 and, after a brief stay in the capital of the Republic, settled in São Paulo, a city beginning to commence a grand cycle of industrial growth and significant cultural transformations. In the early 1950s, he opened an architecture firm in partnership with José Gugliota. After some time, he tired of design pieces exclusively for the homes of elite clients and decided to join a group of joiners and produce small series, leading to the formulation of the L'Atelier factory, which soon began to manufacture office furniture and went from being a joinery of handmade production to an industry of mass production. The first piece of the series was made in 1959; it was an armchair, nicknamed 'Danish' by the staff. Composed of rosewood and upholstery, it features toothpick legs, and the arms and front feet resemble the columns designed by Niemeyer for the Palace of Dawn.

In the early 1970s, with serious financial problems, L'Atelier was sold to a business group, which already owned Laminação Brasil (hardware), the Hevea plastic products industry, and the Labo computer factory. The sale was negotiated with Zalszupin to maintain the position as director of product research and development. Zalszupin expanded the team of designers - which already had Oswaldo Mellone - incorporating Paulo Jorge Pedreira and Lílian Weimberg permanently. The designers baptized the business group and began to act as a creative laboratory.

The team of designers enhanced the technical possibilities offered by four different industrial plants. Hevea, which produced plastic commodities, started to produce a very sophisticated line of design products resulting in the establishment of the brand, Hevea, specializing in household items sold in supermarkets. L'Atelier started incorporating plastic into its product line, producing panels for offices and licensing the Hille polypropylene shell chair designed by Robin Day. In addition to the products sent to the market, the design team of the Forsa group tested new ideas, which form an extraordinary collection and that certainly influenced the work of Oswaldo Mellone and Paulo Jorge Pedreira.

Among his most acclaimed works is the Limestone Table, the success of the piece was determined by the materials. It consists of two simple wooden structures that support a large marble tabletop. Zalszupin lets the material speak for itself. Another renowned design of his was the Romana coffee table, based on a similar design. It has a long marble top affixed to thin, exquisitely curved wooden legs. In his work the Petalas, Zalszupin plays with an organic form inspired by flower petals. The idea works both as a large octagonal table and for a smaller one made of only four elements. Moreover, there is Zalszupin's Andorinha table, another design inspired by nature, taking the form of a swallow. He transforms this inspiration into a multifunctional table with ease, cutting out an opening in the tabletop in which he places a double 'hanger' to be used as a newspaper holder. A newspaper holder can also be seen in his Onda bench. Its sensual lines hint at waves, although Zalszupin does not allow this inspiration to be too obvious. Simple, straight metal legs balance the ergonomic waves of the seat.

His experimentation in the conjoining of different materials resulted in projects such as Veranda or 720. In both armchair designs, Zalszupin explores the possibilities of stretching leather over wooden frames. He exposes the connecting joints and elements of the structures, creating an intriguing visual element.

In his flagship project entitled Dinamarquesa or Danish Zalszupin again played with the idea of a wooden structure and leather seat pulled across the frame. However, in this model, he placed more emphasis on the elegance of the silhouette. His attention to detail and high-quality materials are reminiscent of jewellery, the lower part of its supporting legs are wrapped in what seem to be metal bracelets. The connecting joints are not exposed, yet there is a well-thought-out frame and distinctively curved armrests. Dinamarquesa may be the embodiment of what is best in Zalszupin's designs: where discipline meets the beauty of a liberated, clear line resulting in a harmonious whole that is full of emotion.

The crisis of the 1980s profoundly affected the performance of Forsa group. The design team abandoned the company at the end of the decade. Oswaldo Mellone and Paulo Jorge Pedreira opened their offices, and Jorge Zalszupin dedicated himself exclusively to architecture, an activity he never left.

Martin Eisler (Vienna, Austria, 1913 - São Paulo, Brazil, 1977) was an architect and furniture designer. He was part of a group of European architects and designers who left Europe during the chaos of the Second World War and went to live and work in Brazil. Eisler stood out amongst this group of creatives. His work was at the forefront of modern furniture design in Brazil, which flourished through the 50s and 60s. Eisler's work in partnership with Carlo Hauner (1927-1996) was of particular significance.

Eisler left Europe in 1938 due to the rise of fascist regimes. He first lived in Argentina, where he was settled and worked as an architect, set designer, and interior designer. Eisler opened up an interior design firm Interieur Forma. In 1940, he married Rosl Wolf, the daughter of German immigrants.

Born in Brescia in 1927, Carlo Hauner studied technical drawing and drawing at the Brera Academy in Milan, Italy. In 1948 he successfully participated in the Venice Biennale, after which he moved to Brazil, where he dedicated himself to the design of textile, ceramics, furniture, and architecture. After purchasing a factory from Lina Bo Bardi and her husband Pietro Bardi, he quickly founded a furniture production company, renaming it Móveis Artesanal.

In 1953 Hauner met Martin Eisler, who was looking for help to produce furniture for the home of his brother-in-law, Ernesto Wolf. Eisler reached out to Hauner, marking the beginning of a flourishing partnership. The two men connected, and with Wolf's financial backing, they opened Galeria Artesanal (a store for their company Móveis Artesanal) on a busy street in São Paulo.

Being highly ambitious and with an eye on the international market and the upcoming office market, Móvies Artesanal later changed into Forma. Along with Oca, Forma became one of the biggest names in Brazilian furniture production. Eisler attracted exclusive license to sell Knoll furniture, bringing big names in international design such as Mies Van Der Rohe, Charles Eames, and Harry Bertoia to the Brazilian furniture market. Hauner and Eisler's designs are characterized by Brazilian woods, thin tubular frames, and range from furniture to ceramics and textiles. Some of their most famous designs are the "rib" lounge chair, the "concha/haia" chair or "reversible" lounge chair, both shown in this exhibition. In 1958 Hauner decided to return to Italy to open Forma di Brescia, which catered to, e.g., the embassy of Brazil in Rome and Vatican City. Eventually, Hauner sold his part of the company, leaving Eisler solely at the helm to paint and make wine on Salina, a little isle just above Sicily. After a fulfilled life, the artist, designer, and serial entrepreneur died in 1997. Forma prospered during the 60's and 70's, until Martin Eisler died in 1977. His original company in Argentina still exists and, at the moment, is the sole heir to Hauner and Eisler's Heritage. Although Hauner and Eisler designed and produced many pieces, the depth and quality of their work outlined is only the beginning of their lasting impact on the design world.

Sergio Rodrigues (Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 1927 - Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2014) was a furniture designer and architect. In search of the Brazilian identity, Rodrigues broke away from design constraints and tried to harmoniously integrate the three areas in which we worked; architecture, design, and drawing. He joined the National School of Architecture of the University of Brazil (FNA) in 1947. In 1949, he worked as an assistant professor for David Xavier de Azambuja. In 1951, David Xavier de Azambuja invited Rodrigues to participate in elaborating the Civic Center of Curitiba. The architects Olavo Redig de Campos (1906-1984) and Flávio Regis do Nascimento also collaborated on the project. It was through these contacts that Rodrigues met Lucio Costa (1902-1998).

Rodrigues graduated with an architecture degree in 1951. He moved to Curitiba, where he founded Móveis Artesanal Paranaense, in partnership with the Hauner brothers. In 1954, the Hauner brothers hired him to lead the interior architecture section of the new company, Forma S.A, in São Paulo. During this tenure, he came into contact with other renowned designers such as Gregori Warchavchik (1896-1972) and Lina Bo Bardi (1914-1992).

Sergio's work came at a time of great change for Brazil. Brazil was investing in federal capital, and the Brazilian people were experiencing a cultural awakening in fine arts, music (Bossa Nova), and architecture (the construction of Brasília). Sergio sensed that modern Brazilian architecture lacked contemporary furniture. Sergio's creations, intended to make modern, comfortable furniture suited to the Brazilian tropical climate, availing of wood and leather, soon led him to the new capital where his furniture was ordered on a large scale and taken to Brasília.

Along with essential furniture designers in Brazil, such as Joaquim Tenreiro, and Zanine Caldas, Sergio Rodrigues has played a decisive role in the history of Brazilian furniture. He is the author of various works and always developed furniture consistent with the evolution of architecture during his life.

In 1955, he resigned from Forma, and returned to Rio de Janeiro. Eager to commercialize the production of Brazilian design he opened Oca in 1955. The decades of the 50s and 60s were particularly prolific for Rodrigues. He designed the Mole armchairs, and a variation of the Mole armchair was awarded first at the Concorso Internazionale Del Mobile in1961 in Italy. His design was chosen from a list of 400 designers, and this victory confirmed his international status as a world-class designer. The ISA produced the chair in Italy and exported to several countries under the name Sheriff. It was comfortable and robust and was considered a symbol of national design. Rodrigues intended to design a piece of furniture that expressed national identity. The armchair was associated with a Brazilian way of sitting, inspired by the relaxed and lethargic Brazillian lifestyle. His work is said to have emphasized the relaxation, informality, and rejection of a new lifestyle of the 1960's youth. Many believe that Rodrigues was successful in his endeavour to symbolize the Brazilian identity.

The CD-7, or Lucio Costa chair, was made of solid wood with straw seat and named after the architect, a great promoter of Rodrigues' work. The PL-7Jockey PL-7Jockey, or Oscar Niemeyer armchair, was also constructed with a wooden frame. This chair has braided straw arms carved as unique pieces, with an anatomical design, and constructed through thoughtful consideration of Lucio Costa's work. However, influences from the works of the Danish architect and designer Finn Juhl (1912-1989) can also be seen in the design.

In 1958, Sergio received an invitation to conceptualize pieces of furniture for the, then under construction, national congress building in Brasilia. For the waiting room, he designed the PO-3armchair, which was later named Beto. Beto was composed of a chrome frame, hardwood arms and seat, and a foam backrest. In 1960 he worked on a project with Oscar Niemeyer (1907-2012) and built the table Itamaraty for Brasilia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Darcy Ribeiro, then rector of UnB, invited Rodrigues to design the seats of the Candangos Auditorium, a building designed by the architect Alcides da Rocha Miranda (1909-2001). A similar design of his is the armchair created in 1965 for the Auditorium Instituto dos Arquitectos do Brasil (IAB/DF), in Brasília, which gained an honorable mention in the IAB contest that year, and was used in several Brazilian auditoriums, such as the Anhembi and the São Paulo State Research Support Foundation (Fapesp).

Another famous armchair was the Tonico, created in 1963 for Meia-Pataca, with a roll pad for neck support supported by adjustable straps. In 1973 he designed the Lightweight Kilin PL-104 armchair, made of solid wood and canvas or leather for the seat and backrest.

He also promoted the preliminary stages of the first studies of SR2 - System of Industrialization of Prefabricated Modulated Elements for Construction of Housing Architecture of wood. The prototypes of the buildings are exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro (MAM/RJ). The system was successfully used in the construction of the Yacht Club of Brasilia and two lodging pavilions and restaurants of the University of Brasilia (UnB), in 1962, as well hundreds of units being produced and assembled in the Amazon rainforest.

Dedicated to marketing furniture produced in series at affordable prices, in 1963, he founded the company Meia-Pataca, which was active until 1969. In the late 1960s, he sold Oca. He set up his own studio in Rio de Janeiro, where he worked mainly as an interior architect for homes, offices, and hotels and worked on projects for the Central Bank in Brasilia and the headquarters of Editora Bloch in Rio de Janeiro. The innovative designer received the Lapiz de Plata Prize at the Buenos Aires Architecture Biennial for his work in 1987. In 2006, he won 1st place in the furniture category in the 20th edition of the Design award in São Paulo, with his armchair Diz.

In the 1980s, he developed projects for hotels, such as the DAAV chair and the Júlia armchair. In the 1990s, he continued to design furniture, such as the Chico and Adolpho chairs, made for the meeting room of Editora Bloch. Rodrigues remained consistent in his design style throughout his 50-year career.

Upon examination, it is evident that Rodrigues' preferred choice of material was wood, which he often combined with leather or straw and other natural fibers, such as cotton or canvas, and occasionally with metal. Oca, which started as a modest interior architecture studio, is now held in high esteem and is often referred to when discussing the development of modern furniture in Brazil. Oca integrated contemporary design into the new wave of modernization that Brazil experienced in the mid-twentieth century.