Side Gallery

Side Gallery

WishlistFollow

JAPANESE MODERN

ATELIER MUJI GINZA, TOKYO

28 APRIL – 25 JUNE 2023

The exhibition Japanese Modern, held at ATELIER MUJI Ginza from April 28 to June 25, 2023, explored the evolution of Japanese furniture design throughout the twentieth century and how it reflected changes in patterns of everyday living. Through a selection of objects ranging from low tables, futons, and tatami mats to chairs, sofas, and industrially produced furniture, the show examined how Japanese modernity emerged not through rupture, but through a continuous dialogue between tradition, craftsmanship, and innovation.

Divided across two galleries, the exhibition invited visitors to engage both visually and physically with the works. Gallery 1 presented three domestic settings—a tatami area, a wooden-floor area, and a modular room—illustrating the gradual transformation from floor-based to chair-based living. Gallery 2 allowed visitors to sit on many of the chairs, offering a direct experience of proportion, material, and comfort as key aspects of Japanese design sensibility.

Alongside furniture, Japanese Modern also featured everyday objects such as tea sets and small tables, expanding the definition of design beyond function to encompass atmosphere, ritual, and the quiet aesthetics of daily life. Ultimately, the exhibition proposed that the essence of Japanese modern design lies in its capacity to harmonize the inherited and the new—preserving the spirit of tradition while embracing the possibilities of modern life.

Through a careful selection of objects—from public-facility furnishings to long-lived domestic designs—the exhibition revealed how craftsmanship and mass production coexisted within Japan’s modern identity. Visitors were invited to sit, observe, and sense the tactile qualities of each piece, reconnecting material, body, and function. Japanese Modern ultimately proposed that modernity in Japan is not defined by rupture, but by a quiet continuity—an ongoing dialogue between tradition, simplicity, and innovation.

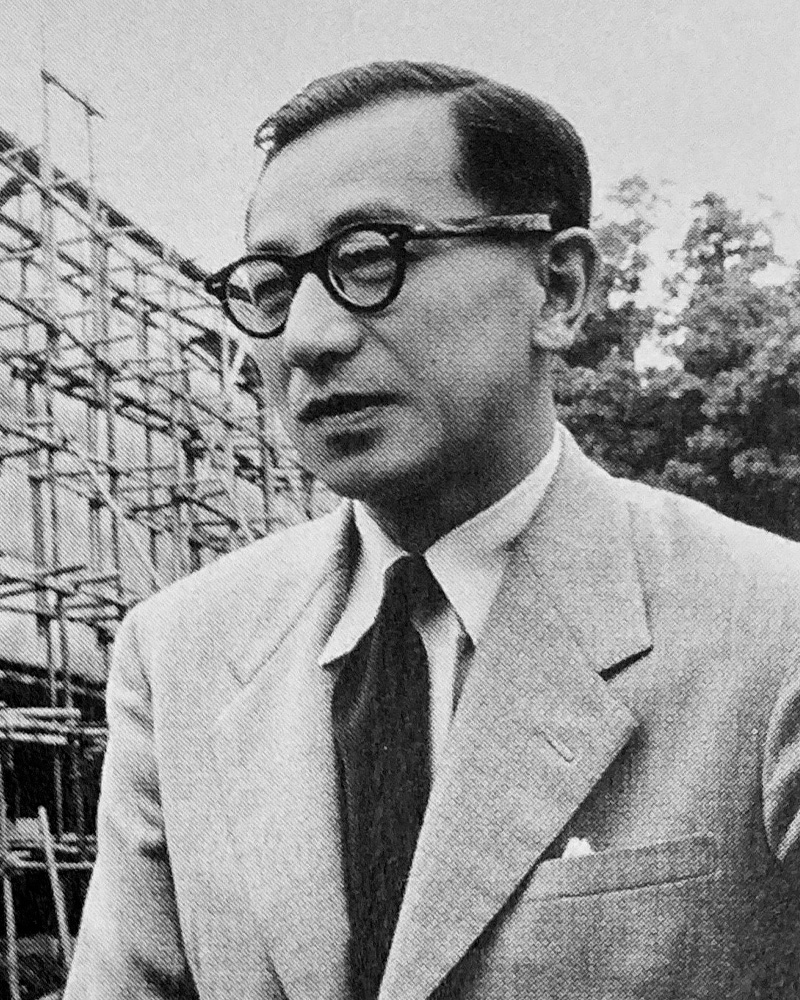

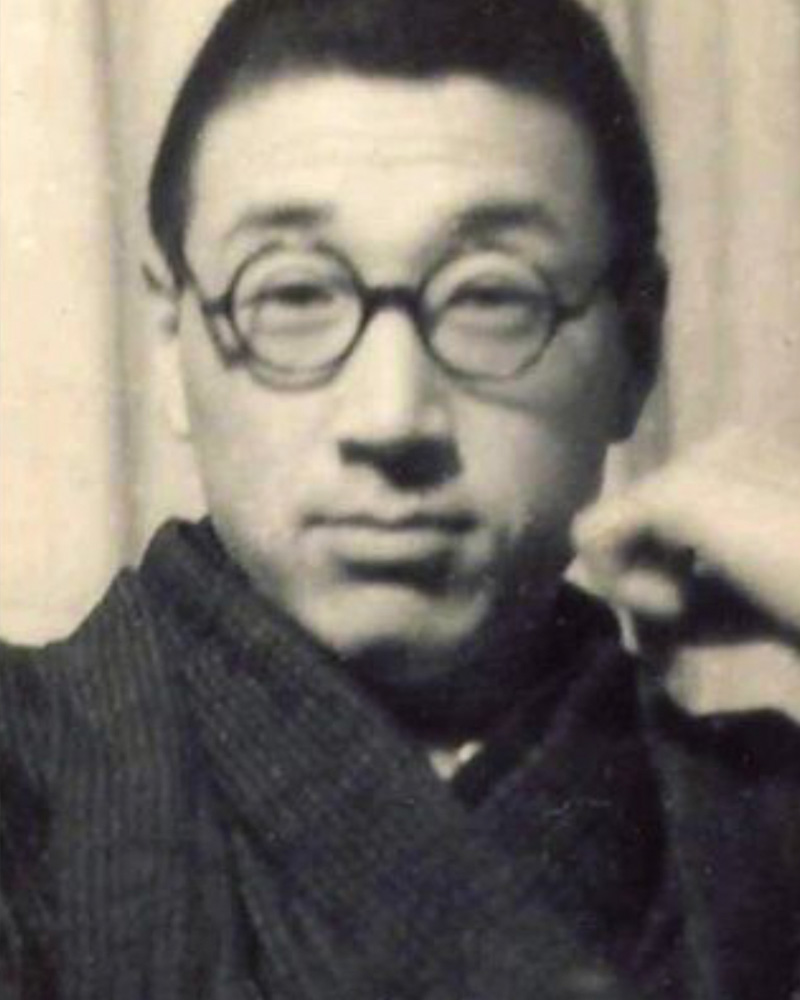

Born in 1912 in Tokyo, Japan, Isamu Kenmochi 剣持勇 was one of Japan's leading interior and product designers, and one of the pioneers who laid the foundations for the design trend known as Japanese Modern. From the chaotic postwar period through the years of rapid economic growth, Kenmochi was deeply involved in Japan's industrial design and the development of living environments. He expanded his activities beyond furniture design to include exhibition design, showroom production, and even the creation of educational systems for design, pursuing a “comprehensive design” aimed at improving the quality of living spaces as a whole.

After graduating from the Woodcraft Department of Tokyo Higher Technical School in 1932, Kenmochi joined the Ministry of Commerce and Industry's Crafts Guidance Center. The following year, he engaged in research on “normative archetypes” for chairs under the tutelage of German architect Bruno Taut, who was then visiting Japan. It is believed that his fundamental ideas about materials, structure, and form were largely cultivated during this period.

After the war, he was involved in designing and directing the mass production of furniture for the housing of occupying forces, creating over 30 pieces of furniture in a short period of time and making a significant contribution to establishing quality standards for mass-produced furniture in Japan. This was not only a practical project during the reconstruction period, but also the starting point for Kenmochi’s pursuit of reconciling industrialization and handcraft.

In 1950, he collaborated with sculptor Isamu Noguchi and architect Kenzo Tange, who were visiting Japan, to create a chair made of bamboo, challenging himself to combine materials, form, and structure. Through this experience, Kenmochi began to seriously consider how to incorporate Japan’s unique materials and culture into modern life. In 1952, he helped establish the Japan Industrial Designers Association (JIDA), alongside Watanabe Riki and Yanagi Sori, promoting the institutionalization and professionalization of industrial design in Japan. In 1955, he founded the Kenmochi Design Institute and began working on a wide range of projects, from furniture to spatial design, all based on a consistent vision.

Kenmochi’s designs emphasized not just aesthetic beauty but harmony with the user’s body, habits, and space, and he viewed furniture as one of the elements that make up a “place.” In his showrooms of the 1950s, he presented numerous pieces under the concept of Japanese Modern (or Japonica), utilizing traditional Japanese materials such as bamboo, washi paper, lacquer, and rattan.

Kenmochi was also active internationally, representing Japan at events such as the Aspen Conference and the World Design Congress. Through dialogue with Charles and Ray Eames and Isamu Noguchi, he promoted the significance of Japanese design in the international community. He had a particularly close relationship with the Eameses, once remarking: “Their work exudes their unpretentious personalities.”

One of his signature works, the Rattan Chair (1958), combines a modern form with comfortable seating, utilizing rattan, a traditional Japanese material. In 1964, it was selected for the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. He also undertook numerous other projects that shaped the landscape of postwar Japan, including furniture for Hotel Okura’s guest rooms, the interiors of Haneda Airport’s VIP lounges, exhibition spaces for international trade fairs, and signage plans for public facilities.

Underlying his work was a deep understanding of Japan’s climate and materials, and a constant inquiry into how to embed them into modern life. His designs were both functional and poetic, Japanese yet international. Even today, Kenmochi’s ideas and practices continue to influence designers worldwide, and his significance as a central figure in shaping Japanese modernism is being reevaluated.

ISAMU KENMOCHI AND TENDO MOKKO

Isamu Kenmochi was a man who introduced the concept of design to Japan throughout the prewar and postwar periods, working to raise awareness of its role and improve people's lives. In 1932, he became an engineer at the National Crafts Training Institute of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry (now the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry). In 1933, architect Bruno Taut was appointed to the institute on a contract basis, and Kenmochi studied under him, researching the “standard prototype of chairs.”

In 1952, he became the first Japanese designer to visit the United States, where he was deeply influenced by his encounter with Charles and Ray Eames. This visit forced Kenmochi to confront the issue of establishing and communicating the originality of design in his own country, and he came to develop the concept of Japanese Modern. The same year he returned to Japan, he was involved in the founding of the Japan Industrial Designers Association, with the aim of establishing and improving the industrial design profession. In 1955, he also helped launch the Japan Design Committee, which aimed to promote good design. That same year, he went independent.

Kenmochi’s relationship with Tendo Mokko began during the wartime National Crafts Training Institute. While providing instruction in both design and technique for furniture production using molded plywood, he also collaborated with architects to design a variety of products, creating many of Japan’s most famous postwar interiors. His diverse work spanned a wide range of fields, including the Yakult lactic acid bacteria drink, a design beloved worldwide to this day.

From the public sector to the private sector, spanning the prewar and postwar periods, Kenmochi supported Japanese design from its early days and contributed greatly to its global reach. In June 1971, he oversaw the design of Japan’s first high-rise hotel, the Keio Plaza Hotel, and elevated Japanese Modern to a new level. However, Kenmochi’s overwhelming workload led to depression, and he died by suicide on the day of the opening party.

The Kenmochi Isamu Design Institute subsequently changed its name to the Kenmochi Design Institute, where it has continued to support Japanese design for half a century.

A design that cannot be imitated

“I thought there was a guy who looked pretentious, and it was Kenmochi. He was the type I didn’t like,” says Matsumoto Tetsuo, director of the Kenmochi Design Institute, laughing as he recalls meeting Kenmochi. After Kenmochi passed away, Matsumoto took over the firm, and the Kenmochi Design Institute has continued to produce many masterpieces ever since. In addition to furniture and interiors, they also produced street furniture that can still be seen in various places today, the interior and exterior decoration of different train carriages including the Shinkansen, and the yellow handy mop from Duskin. They have produced a wide range of products and spaces.

Kenmochi and Matsumoto’s encounter dates back to the days of the Industrial and Crafts Research Institute. Matsumoto, who graduated as one of the first students from the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, Chiba University, joined the Industrial and Crafts Research Institute in 1953. This was the year after the Ministry of Commerce and Industry’s National Crafts Guidance Institute, established in 1928, was reorganized as the Industrial and Crafts Research Institute under the Ministry of International Trade and Industry. Matsumoto, worried about finding a job, visited the institute on the recommendation of his mentor. The written exam was held that day, followed by an interview that afternoon, where he was hired. Kenmochi, who was head of the institute’s design department at the time, was looking for someone with an architecture degree, and Matsumoto recalls with a wry smile that the groundwork had been laid in advance.

Kenmochi met Eames and George Nelson during a visit to the United States in 1952, and Matsumoto continues: “He said that when he saw designers working independently in the United States, he became convinced that the same era would surely come to Japan. And because all the people designing interiors in the United States had studied architecture, he wanted people who had studied architecture.”

When Matsumoto joined the institute, Kenmochi was away at the Aspen International Design Conference in Aspen, Colorado, USA (held from June 23rd to July 1st, 1956, at which it was decided that the World Design Conference would be held in Japan in 1960. That conference is known for inspiring the Metabolism movement in architecture and for having a major influence on students such as Miyake Issey and Ishioka Eiko, who were students at the time). When Matsumoto saw Kenmochi upon his return to Japan, he had the same impression as mentioned above.

“A white shirt with a bow tie was something that didn’t exist in Japan at the time. Later, Kenmochi told me that Eames and Nelson also wore bow ties, which were convenient because they didn’t hang down when they were drawing, and that made sense. In an era before air conditioning, Kenmochi wore suits even in the summer. His father had served as an army major, so he must have been strict in his upbringing. When handing out summer bonuses, he would do so wearing a jacket and tie, but it was so hot for us staff members that we were dressed in shorts and running shirts. Kenmochi would get mad at us for not doing things properly at milestones, so one of the staff members would take turns wearing a jacket kept in the office to go and collect it. So Kenmochi must have been a bit eccentric.

When we received royalties for our articles in magazines and newspapers, he would often take the whole staff out to the movies. Since he was paying for everyone, our income was actually in the red. Sometimes Kenmochi would get scolded by the accounting department afterwards.”

Kenmochi left the Industrial and Crafts Research Institute in June 1955 and opened his own office. He then dismissed Matsumoto, who was in his second year at the institute, saying: “I’m not getting paid. I’ll call you when you’re ready to do it, so until then, just help out at night.” After finishing his work at the institute, Matsumoto began to commute to Kenmochi’s office. “I remember thinking it was cool back then when they called me the night chief, but I was always working until the last train,” he recalls.

Matsumoto then left the Industrial and Crafts Research Institute after four years there and began to demonstrate his skills as chief designer under Kenmochi.

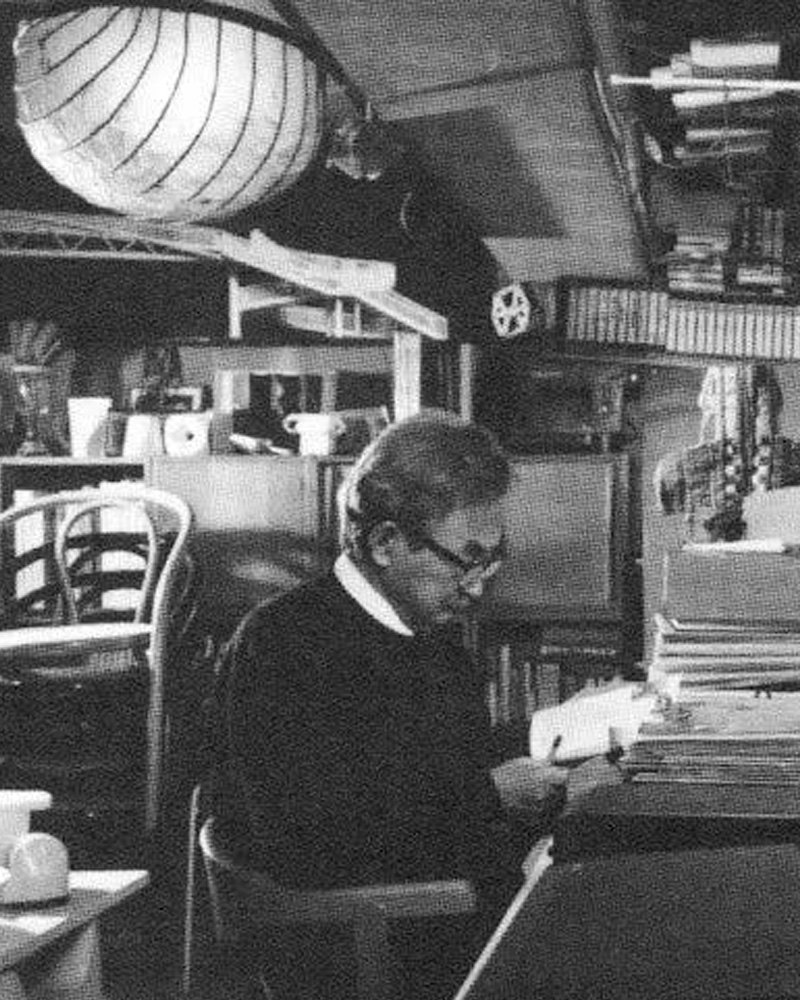

“Kenmochi originally studied woodworking. He was head of the woodworking section at the Industrial Crafts Testing Institute before becoming head of the design department. He knew a lot about wood processing, and I had no choice but to study it myself. How can you draw blueprints if you don’t know how to make something? In short, he was very skilled at drawing. When I first met him, he was standing and drawing full-scale drawings freehand. He would even quickly sketch them during a meeting. He was someone you couldn’t compete with if you made suggestions based solely on intuition.”

When Kenmochi first traveled to the United States, it was difficult to cover everything with government funds. He sold his Nikon camera there to supplement his travel expenses and instead purchased a cheaper one. After returning to Japan, Kenmochi had to travel around the country to give reports to instructors, and color slides were essential.

“It was his first time going to the US, and he had no money, so he traveled on a passenger/cargo ship. He entered the US from Guam by ship, passed through Hawaii, and arrived in San Francisco on the West Coast, where he stayed at the Eames House in Los Angeles. He had been exchanging letters with the Eames and others. This time, he traveled across the continent by coach to meet George Nelson on the East Coast. He stopped off at Frank Lloyd Wright’s place along the way, visiting the East on the way there and the West on the way back.

Information wasn’t as readily available back then, and Kenmochi’s English was broken, but he still managed to cross the US alone. It was strange, even though he wasn’t intimidated. He extended his stay, saying he still had more to learn. Then, after returning home, he generously shared the knowledge he had gained, showing people what was happening in the US. At the time, it was rare to see Eames furniture in person. So I’m sure everyone was amazed when he showed them that molded plywood chair. And that’s when the term Japanese Modern came up.”

“Matsumoto continues: ‘Kenmochi didn’t come up with the term Japanese Modern. His stay in the US coincided with the rise of Scandinavian furniture, as Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland strategically began selling furniture, tableware, and textiles. The buyer explained to me that in America, even the average customer has a certain style that comes to mind when they think of Swedish Modern. So the idea was that Japanese furniture would also have to develop a market with a style people would associate with Japanese Modern.

In other words, Kenmochi reported that Japanese furniture needed distinctive features to make an impact on the world market, but at the time some people were annoyed, saying that Kenmochi had come back all American. He was wearing a bow tie, for example. They mocked him, saying that he had only a Japanese taste.’”

Matsumoto believes that Kenmochi’s early visit to the United States had a profound impact on the entire furniture industry. By sharing his encounters with various designers and stories with the industry, he aimed to raise the morale of Japanese design. Kenmochi articulated and advocated the concept of Japanese Modern. Its merits and demerits eventually escalated into a debate still rare in the Japanese design world, resulting in the opening essay (page 32) of this book. Its essence lay in the pursuit of high-quality, original design that combined modern Japanese lifestyles with industry, handicrafts, and crafts.

Matsumoto also describes Kenmochi’s own designs as truly inimitable. The rattan lounge chair (now manufactured and sold by YMK Nagaoka) from Yamakawa Rattan features a seat made of woven wood, while Tendo Mokko’s Kashiwado chair features a seat carved out of stacked wood. Both chairs are simple in concept yet richly unique. Matsumoto recalls that both pieces of furniture began as Kenmochi’s sketches.

“On the other hand, Kenmochi would often ask me to come up with ideas. When I handed him a sketch, he would make corrections. I would then respond and rewrite the drawings. This exchange continued, and we got closer to completion. Of course, Kenmochi Isamu was the sole name in the public eye, so I didn’t use my name. So when I took over, we decided that the design was done by the Kenmochi Design Institute. If Kenmochi’s designs have a wide range, I think it’s because they were born from a simple desire to do something, to make something, and then they took shape.”

A respected senior, Isamu Kenmochi

Imazaki Taku, who joined the Industrial and Crafts Research Institute in 1955, was a student at the Tokyo University of the Arts at the time.

“I used to go to see Kenmochi-sensei’s lectures at the Kogei Shidosho. The lectures were about German modern design and Bauhaus. He talked about works by Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, but also about Bruno Taut’s stay in Japan, which I found very interesting. Later, I went to work at the Kogei Shidosho, and Kenmochi-sensei was still there, so I was very happy.”

Imazaki recalls:

“Kenmochi-sensei was really stylish. He was strict about manners and appearances. Even when it was hot, he wore a jacket and tie, never casual clothes. He never looked sloppy. He always kept his dignity.”

Shimizu City and Kenmochi

Kenmochi was also deeply connected to Shimizu City, Shizuoka Prefecture (now part of Shizuoka City). He was invited to be an advisor on local industry promotion and was involved in developing local crafts, including bamboo products and furniture. He also gave lectures and provided guidance to young local designers, leaving behind a strong influence in the region.

Shimizu was one of the first cities to embrace Kenmochi’s concept of Japanese Modern in daily life. His ability to integrate local traditional techniques with modern industrial design helped raise the standard of regional industries and connected them to the national market.

Final years and legacy

In June 1971, Kenmochi completed the design of the interiors for the Keio Plaza Hotel in Tokyo, Japan’s first high-rise hotel. This project symbolized the culmination of his vision of Japanese Modern, combining functionality, elegance, and modern technology while retaining Japanese identity.

However, the enormous workload, accumulated stress, and the pressures of being at the forefront of Japan’s design world took a heavy toll. On the day of the hotel’s opening party, Kenmochi died by suicide. He was 59 years old.

Despite his tragic end, Kenmochi’s legacy has never faded. His philosophy of merging modern industrial design with traditional Japanese culture, his commitment to raising the quality of everyday life, and his pioneering work in creating a profession for industrial designers in Japan continue to inspire new generations.

The Kenmochi Design Institute, renamed after his passing, carried forward his vision. Under the direction of Matsumoto Tetsuo and later successors, it continued to produce interiors, furniture, and products that reflected Kenmochi’s approach to design: functional, humane, and deeply rooted in Japanese culture.

Today, many of Kenmochi’s works are preserved in museum collections, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. His designs, such as the Rattan Chair, remain timeless examples of how Japanese sensibilities can be expressed in modern form.

Kenmochi Isamu’s life embodies both the challenges and possibilities of design in postwar Japan. By bridging tradition and modernity, craft and industry, local and global, he helped shape the foundation of Japanese modern design. His ideas, born out of dialogue with both Japanese heritage and international movements, continue to resonate, affirming his place as one of the central figures of twentieth-century design.

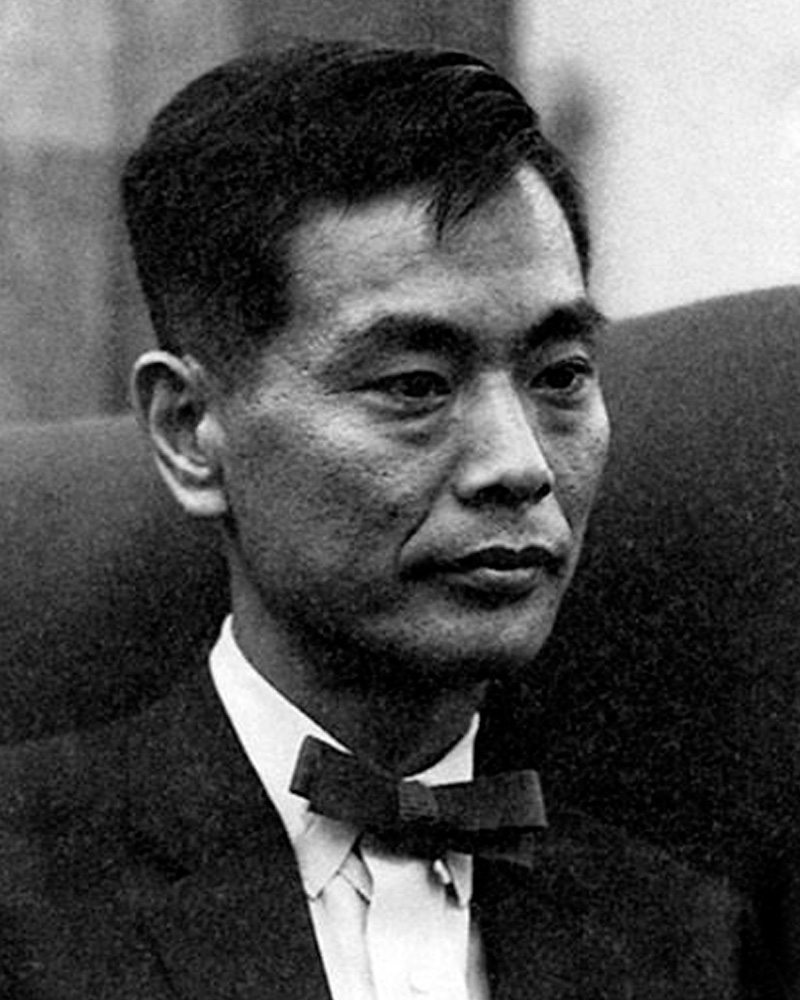

Junzō Sakakura was born in 1901, in the small rural world of Gifu Prefecture, Japan. His early life was rooted in simplicity — tatami floors, wooden structures, the everyday intimacy of Japanese homes. That sensibility never left him, even as he grew into one of the great voices of modern architecture.

At first, he studied art history at Tokyo Imperial University, fascinated not so much by the structures themselves as by the stories and aesthetics behind them. But the pull of design was too strong. In 1929, he made the bold move to Paris, where fate — and a few connections — carried him to the atelier of Le Corbusier. In Paris, Sakakura entered a world of rigorous geometry, reinforced concrete, and radical visions for the future. He worked his way up in the studio until he became Le Corbusier’s chief assistant. The experience changed him profoundly. Here was a Japanese man, steeped in the traditions of wood and tatami, immersed in the epicenter of European modernism. He didn’t abandon one for the other; instead, he began to imagine how both could coexist.

His breakthrough came in 1937, when he was asked to design the Japanese Pavilion for the Paris International Exposition. The result was striking: a clean, modern structure lifted above the ground, filled with light, circulation, and rational form — yet quietly carrying the harmony and restraint of Japanese tradition. It won the exposition’s Grand Prix and marked Sakakura as a bridge between worlds. After the war, Japan was in ruins, and Sakakura returned home determined to help rebuild. He opened his own office and quickly became known for public works that combined functionality with elegance. One of his most beloved projects was the Museum of Modern Art in Kamakura (1951), a serene place where modernist concrete frames blend with surrounding gardens and ponds.

He collaborated with fellow Japanese modernists like Kunio Maekawa and Junzō Yoshimura on the International House of Japan in Tokyo, and he was entrusted with executing Le Corbusier’s design for the National Museum of Western Art (1959). He also shaped the public life of a rapidly urbanizing Tokyo with station plazas, department stores, and civic halls. Through it all, Sakakura held fast to a principle: design should serve people. Buildings, yes — but also the smaller things, the objects that people touched every day.

Sakakura never separated architecture from interiors. To him, a room was incomplete without furniture that fit its proportions, materials, and spirit. This belief led him to design a range of chairs and tables, often in collaboration with Tendō Mokko, a Japanese manufacturer specializing in molded plywood. One of his earliest forays into furniture came in 1950, when he entered the Museum of Modern Art’s international competition for low-cost furniture in New York. His “Bamboo Chair” won an honorable mention. The design was clever and economical — a simple seat born of modest materials — reflecting both the resourcefulness of postwar Japan and his own drive to create for everyday life.

He continued refining his ideas through the 1950s and 60s. Among his most admired works is the Lounge Chair, Model 5016 (1957), produced by Tendō Mokko. With its gently curved plywood frame, upholstered seat, and low, inviting stance, the chair balances comfort with understated elegance. It became a quiet classic of Japanese modern furniture.

Sakakura also designed the Teiza Chair, unveiled at the 1960 Milan Triennale. Low to the ground, with a sled-style base and molded plywood frame, it translated traditional Japanese floor-sitting customs into a modern form. This was Sakakura at his most insightful — merging cultural heritage with global modernism.

Other pieces, such as the 3222 side chair from the mid-1950s, show his focus on functionality, clean lines, and materials that could be adapted for mass production in a recovering economy. Each design carried the same philosophy: simplicity, human comfort, and a quiet dialogue between past and future.

Sakakura’s life was not only about monumental buildings or iconic pavilions. It was about balance — between East and West, tradition and modernity, architecture and furniture. He saw no hierarchy between a museum and a chair; both shaped human experience, both deserved thought and care. He died in Tokyo in 1969, but his legacy continues to ripple through Japanese design. His buildings remain landmarks of postwar modernism, and his furniture has gained new appreciation among collectors and design enthusiasts worldwide. When you sit in one of his chairs — low, simple, comfortable — you can feel the same principles that guided his architecture: clarity, restraint, and a deep respect for human life. Sakakura believed design should make living better, whether through the walls of a museum or the curve of a seat. In that belief, he built not just structures, but a philosophy that still resonates today.

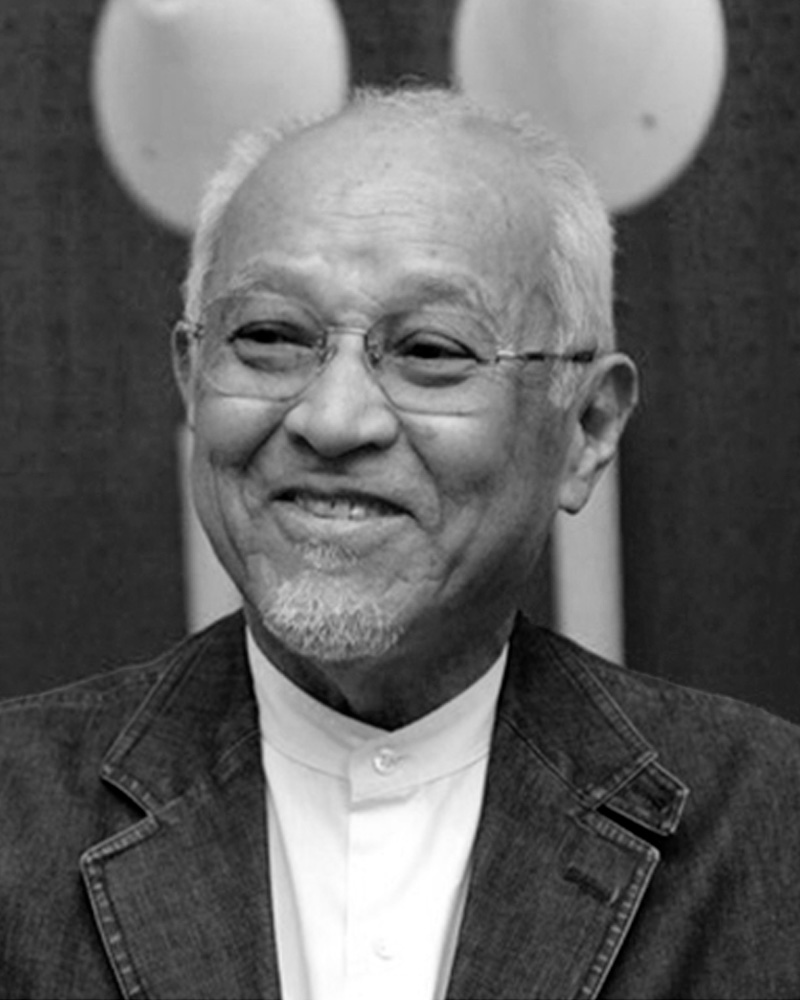

Katsuhei Toyoguchi 豊口克平 was born in Kemanai of Kazuno city. Akita Prefecture. He was the second son of his father Kamegoro, who worked for the Akita Prefectural Office, and his mother Yashi.

Toyoguchi had four brothers and three sisters. After graduating from the Department of Machinery at Akita Prefecture Industrial School, he became an assistant at the Secondary Industrial School in Yokohama. He was one of the most promising future engineers, but he suffered through the Great Kanto Earthquake. Luckily, he was not killed by it, so he returned back to Akita. While working as a substi tute teacher, he took the entrance examinations and was admitted to the Tokyo Advanced Crafts School, Department of Craft Design. At this school, he studied under Kurata Munechika who was strongly drawn to German furniture and architecture. Kurata had just returned from studying at Bauhaus. Toyoguchi became a member of the Keiji kobo which was led by Kurata. Instead of the original idea of metaphysics, they put more emphasis on design and shape.

After working with the Keiji Kobo, he started to work at the Crafts Institute (later called the Industrial Arts Institute) with a rec- ommendation from Kunii Kitaro. He then became an independent designer as well as a professor at Musashino Art University. Department of Industrial Design. Although he was in charge of a series of different projects, his delicate voice and gentle looks always remained the same. The life and death experiences he has had, such as the Great Kanto Earthquake and his battle with lung cancer, may have brought more maturity to his personality.

After leaving the Industrial Arts Institute in 1959. Toyoguchi founded the Toyoguchi Design Laboratory.

When he first started out, he borrowed space in the KAK office of the industrial designer, Akioka Yoshio, to work on displays. Any other work was handled in the living room of his teacher and colleague from the Keiji kobo, Kurata Munechika.

The Toyoguchi Design Laboratory was divided into two different departments: Industrial Design and display. Each team would come up with specific ideas and sketches. He always said "Will you draw this for me?" This always meant that his final decision was to go ahead with that design.

He must have developed this way of managing projects from his extensive experience as a team member of the governmental system of the Crafts Institute. It is a clever system which makes teamwork go smoothly. By adding the gentle personality of Toyoguchi to the system, it is not so difficult to understand why they have produced so many well-designed products.

In fact, Toyoguchi was my superior when I first joined Musashino Art University as a part time lecturer in 1964. In his laboratory, he spoke casually and we enjoyed a variety of conversations. One time he told me that he had hated himself for being soaked in the bureau- cratic atmosphere for such a long time that he finally decided to leave the Industrial Arts Institute. Yet he was unsure how he would be received as a freelance designer and whether or not he would receive enough work. He left the Industrial Arts Institute at the age of 54; maybe he was worried that he would not have enough time in his life to become successful.

However, such worries were unnecessary. Many clients whom he worked with while he was at Industrial Arts Institute, such as the Suzuki Motor Corporation, Olympus, and Hokushin Denki continued to work with him. His honest personality also helped him find new clients of different public services. Since 1960, he had been very busy exhibiting Japanese Industrial Design for trade shows in Moscow. Mexico, Seattle, and even a trade show hosted in cruise ship. Although Musashino Art University is a private university, it allows professors to operate private business while teaching students. Toyoguchi worked as a designer who was in touch with the real world. while devoting his efforts to education.

Kurata Munechika, who had just returned from Bauhaus, was the leader of the Keiji kobo which had started with just nine members. including Kurata and Toyoguchi. Although a few members changed, their acitivity went on for almost 10 years. The basic aim of the Keiji kobo was to apply design to the daily lives of Japanese in order to improve their quality of living. Thus, they researched and developed "standard furniture planning".

Toyoguchi joined the Crafts Institute by a recommendation from Kunii Kitaro. He worked there from 1933 to 1940, while continuing to work at the Keiji Kobo. In 1940, Bruno Taut was invited to work with Director Kunii. Applying the knowledge of Bauhaus with the added concept of the Norm by Taut, he proposed an experiment with a pro- totype chair. However, Taut commented that "any scientific experi- mental data is useless", so he gave up on his idea. After Taut left, he got together with Kenmochi Isamu and Fujii Sanai to visit the Naruko Hot Spring. They contributed to ergonomic studies by sitting on piles of snow to measure the curve and angle of the human buttock. Toyoguchi also used two pieces of metal sheet connected by a free moving steel rod to measure the average seating position. Needless to say, this sort of determination has resulted in chairs that are comfort- able and loved by their users for many years.

When we talk about Toyoguchi, we cannot leave out his wife, Fumiko. Before starting their newly married life, they decided togeth- er that each of them would bring their own desk and books and con- tinue to study throughout their lives. In 1981, they celebrated their golden anniversary by publishing a booklet called " Being a Couple for 50 years". It was a compilation of their writing, Toyoguchi's sketches, and Fumiko's poems. Fumiko described Toyoguchi as the first per- son at work to treat women as equal to men. This illustrates that Toyoguchi had a different attitutude towards women at a time when women were assumed to have only an assisting role to men. The female designers in his office were treated as equals. This kind of trust between designers was the creative driving force of great designs.

Matsumura Katsuo 松村 勝男 (1914-2005) is the third son of six children to a father who owned a publishing company. With a desire to create solid objects, Matsumura studied woodcraft at the Tokyo Prefectural Craftwork School in Suidobashi. After graduating, he attended the Industrial Art Training School which is a part of the Tokyo Art School. The headmaster and professors belong to both schools. While he was studying, he worked part-time at the office of Yoshimura Junzo.

He was hired in Hida Takayama, but the War broke out and he was sent out as a soldier. When he finished serving in the army, he met Yoshimura again during their evacuation. He then began to work for him. Shortly after, the Yoshimura Architecture Office was founded and Matsumura officially joined. His talent was readily accepted just like the talent of Choh Daisaku of Sakakura Junzo Architecture Office and Mizunoe Tadaomi of Maekawa Kunio Architecture Office. These three designers received a second prize Mainichi Industrial Design Award at the "Furniture Collection Exhibition".

If people were asked to vote on Matsumura's most famous piece, they would choose the Gama (Sedge) Chair. It is both durable and strong. However, I would vote for the dining chair T-0635B.

People thought of Matsumura as a passionate and strong man. However, he was very delicate, thoughtful and fair in his criticisms.

Matsumura met many architects and designers of his generation through Watanabe Akebono, the famous editor-in-chief of the maga- zine "Modern Living (Fujin Gahosha)" which was first published in 1951. Matsumura worked especially with Masuzawa Jun to design fur- niture. One of their famous works is the Shinjuku Fugetsudo of Tokyo, a Mecca of modern design where many young people gather. The design of the cafe, Shinjuku Fugetsudo, was very simple and functional. Chairs lined up along a concrete wall. Although Matsumura was an employee of the Yoshimura Architecture Office, these works were done independently. Later he decided to leave the office.

In 1959, Watanabe Riki asked him to be a co-founder of Q- Designers. However, Matsumura was never able to get used to the idea of a design team. He became independent the following year. Having gone through many trials and activities, he finally found his own destiny: the perfecting the design of low cost furniture. Matsumura himself always said that the limited living space in Japan requires that all design be small in size and lightweight. It is a design- er's dream for his product to be loved for a long time, to finally let the design leave his hands and become mass-produced for the public.

His furniture is not influenced by fads; the public can enjoy a prod- uct for a long time. Low cost furniture doesn't have to look cheap. To satisfy these conditions, the dining chair T-0635B was born.

Matsumura wrote a series of articles called "A Story About Becoming a Designer" in the issues of "Furniture Industry Publication" from January to June of 1984. Although it was only a six month-long series, the story was magnificent for describing the life of Matsumura as a designer for at that period in time.

At the beginning of his story, Matsumura describes his first impression of the exhibition "Tradition, Selection, Creation". It show- cased the work of Charlotte Perriand, a furniture and interior design- er. Perriand was a partner of the French architect, Le Corbusier. Perriand's invitation to Japan was very coincidental. Sakakura Junzo was an admirer of the logic of Le Corbusier's architecture. With a rec- ommendation from Maekawa Kunio, Sakakura joined Le Corbusier's office in 1931. After his return to Japan, the Trade Department of the Ministry of Business and Industry asked him to recommend a foreign designer who could come to Japan to train designers. Without a moment's hesitation, Sakakura recommended Perriand.

I heard that Perriand was a small and charming lady and yet she was hardworking and decisive. One year before World War II broke out, Perriand left the port of Marseilles by ship. It took her two months to get to Kobe, Japan. It only took her seven months to visit every region of Japan for her work. Once the war had started, all ships returning to France were stopped. She was forced to take a flight to Indochina to catch a withdrawal ship and finally return to Paris. Her courage and passion has had a great influence on Japanese designers.

When Matsumura was 40 years old he started to work with manu- facturers more often than architects. He made designs for mass pro- duction and developed the use of the Japanese Larch. The seed that Perriand sowed in the heart of the 18 year old Matsumura has surely borne much fruit.

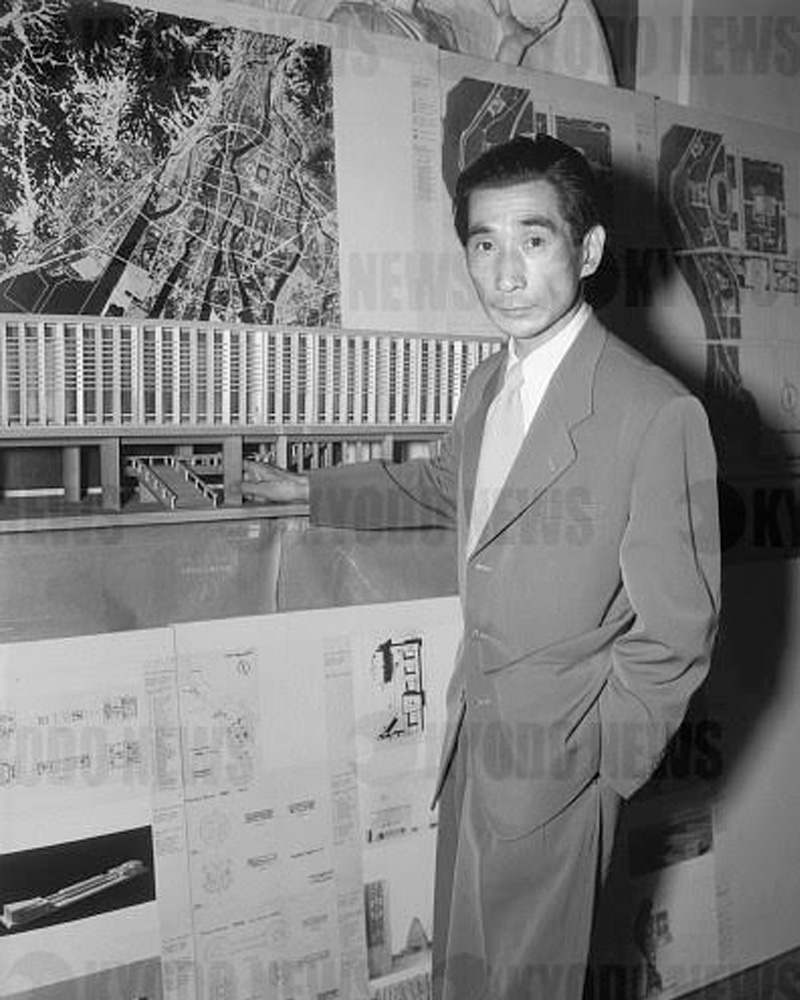

Born in Sakai City, Osaka Prefecture in 1913, Kenzo Tange 丹下健三 enrolled in the Department of Architecture at the Faculty of Engineering at Tokyo Imperial University, inspired by Le Corbusier. After working at Kunio Maekawa Architects, he went on to graduate school at the University of Tokyo. After graduating, he taught at his alma mater from 1946 to 1974, presiding over the "Tange Laboratory." He nurtured many outstanding talents, including Takashi Asada, Yukio Otani, Fumihiko Maki, Arata Isozaki, Kisho Kurokawa, and Yoshio Taniguchi. In 1961, he founded the Kenzo Tange + Urban and Architectural Design Institute. Around the same time, he designed numerous masterpieces incorporating architectural beauty, including the Kagawa Prefectural Office Building, the National Indoor Gymnasium (now the Yoyogi National Gymnasium), and St. Mary's Cathedral, Tokyo. Following the proposal for the "Tokyo Plan 1960" in the 1960s, he was involved in Japan's national projects, such as the masterplanning of the venue for the 1970 World Exposition held in Osaka. From then on, he increasingly became involved in national projects overseas, expanding his activities to a global scale. His later masterpiece, the New Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building, incorporated postmodern trends, and throughout his life, he continued to explore new architectural possibilities without clinging to his past works. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum (now the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum) was the first building constructed after World War II to be designated an Important Cultural Property, followed by the National Gymnasium. Tange passed away in 2005.

Kenzo Tange worked with furniture manufacturer Tendo Mokko on numerous projects, beginning with the spectator seating for the Ehime Prefectural Civic Center, designed by Tange in 1953. The Kagawa Prefectural Government Building, still considered one of his masterpieces, was Tange's first architectural project, with Isamu Kenmochi responsible for the interior design. Tendo Mokko worked with Tange on numerous projects during Tange's prime, but as Tange's work expanded globally, opportunities for collaboration decreased. However, in 1990, they delivered the largest piece of furniture ever to the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building, a record that remains in the memory of the present day. Since then, they have supplied furniture to hotels around the country, including Prince Hotels and the Tokyo Dome Hotel. In recent years, they have also reproduced the "T-7304" and have been producing and repairing additional chairs for children, including the one delivered to the Yukari Bunka Kindergarten in 1967. X

Tange’s career spanned continents and decades. He mentored a generation of architects who carried his ideas into new realms. He reshaped Tokyo and left his mark on cities around the world. In 1987, he received the Pritzker Prize, the highest honor in architecture — recognition not only for his buildings, but for his vision of architecture as a bridge between tradition and modernity, humanity and technology.

Kenzo Tange died in Tokyo in 2005, but his legacy endures. His buildings still inspire awe, his plans still provoke debate, and his furniture rare, precise, and quietly powerful serves as a reminder of his belief in design as a total work of art. From the skyline to the chair, Tange sought harmony, innovation, and a future shaped by thoughtful design.

Daisaku Cho 長 大作 was born in the former Manchuria on September 16th, 1921, as the eldest of six siblings. After graduating from Kaisei Junior High School in Tokyo, he was accepted into the Faculty of Economics at Waseda University, but his father opposed his decision, saying, "If you're going to such a boring place, go to the military academy instead," so he re-applied for art school. The following year, he entered the Department of Architecture at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (now Tokyo University of the Arts). He was an artistic family, with three of his six siblings also studying at the same art school and his father was a doctor.

He then joined the design department of a construction company, but was encouraged by a senior at school to join the Sakakura Junzo Architectural Institute. Sakakura Junzo studied under the famous architect Le Corbusier and worked in Paris, where he was in charge of the Japan Pavilion at the Paris World's Fair and won the Grand Prix in the architecture category. He then returned to Japan and opened the Sakakura Junzo Architectural Institute in 1940. After joining the institute, Cho's main work was overwhelmingly furniture design.

He designed the chairs and tables for the International House of Japan (the architecture was jointly designed by Kunio Maekawa, Junzo Sakakura, and Junzo Yoshimura), which was established in 1952 with the aim of international exchange and intellectual cooperation. He was also involved in the chairs and tables for the Tea Lounge of the International House of Japan, which reopened in 2006 after being retrofitted with earthquake-resistant structures. Cho has been working with this famous building for over 50 years.

In 1957, he was involved in the architecture and furniture design of the Fujiyama Aiichiro residence, and in 1958 he was in charge of the architecture and furniture design of the residence of his predecessor, Matsumoto Koshiro. It was at this time that his masterpiece (the Low Seat Chair) was born. It is well known that the prototype for this was the Bamboo Basket Low Seat Chair designed by Junzo Sakakura. It is characterized by a relatively large surface area to prevent damage to Japanese tatami mats. It can be seen placed on the verandas of inns and old houses. It is a beautiful chair that exudes emotion. Naga redesigned the back and seat to a fabric-covered structure made of quadratic curved plywood, and the masterpiece Low Seat Chair was born. Further improvements were made thereafter, and the Low Seat Chair was exhibited at the 12th Milan Triennale in 1960.

Regarding design, Cho wrote, "My designs are always in development, and there is no such thing as a completely finished product. In particular, when it comes to chairs, I pursue comfort and make repeated improvements." It is speculated that Cho was influenced by his surroundings, such as Junzo Sakakura and the wife of Koshiro Matsumoto, which deepened his more modern way of thinking.

Through this work, he was in charge of the architecture and design of "Terrace Ray" and "Karuizawa Mountain Villa", and it seems that he still maintains a close relationship with the Matsumoto Koshiro family. In particular, Mrs. Masako is said to be a great benefactor to Mr. Naga, who said, "Masako was one of the people who had a great influence on my subsequent work, and I consider her my greatest benefactor, second only to Professor Junzo Sakakura. She provided me with a lot of support, both professionally and financially. Masako had a great aesthetic sense and was very critical of design."

In 1960, Sakakura Junzo Architectural Institute was in charge of the Japanese section of the 12th Milan Triennale. Kitamura Shuichi was in charge of the venue layout, and Cho was in charge of the furniture design, and the two won the Gold Award. This was a remarkable achievement, as they had won the Gold Award at the previous 11th Triennale for Watanabe Riki's Trii Stool.

He wrote about that time, "I stayed in Milan for half a year until the withdrawal. However, unlike now, it was a time when people could not travel abroad freely, so during my stay I was able to travel here and there and visit architectural works, which were very valuable experiences. At that time, there was no high-quality, well-designed furniture in Japan, and imported products were rare and expensive, so it was common for architects who designed buildings to also design all the furniture inside."

Yanagi Sori 柳 宗理 was the first born of Yanagi Soetsu, father, philoso pher, and the founder of "Mingei Undou (folk craft movement)", and Kaneko, mother and vocalist.

Yanagi Sori started out at the Arts School (currently Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music) as an oil painting major- a field that is completely different from design. I suspect that Yanagi first realized he had an interest in design when he worked as an interpreter for Charlotte Perriand. Perriand was invited to visit Japan by the Ministry of Business and Industry. While he was working for Toyo Kaikan in Manila, Philippines, he became more internationalized through his experiences with the rich and materialistic lifestyle of the U.S. He experienced Japan's loss of World War II while he was abroad. He had to run for his life through the jungle in order to escape. This experience had a significant impact on the rest of his life.

His independence and his strong desire to maintain his own sense of style shows that he intends to remain a freelance industrial design- er for the rest of his life.

In 1952. Yanagi won first prize at the 1st New Industrial Design Competition hosted by Mainichi Shinbun. At that time, the prize was 1 million Japanese yen, which is now equivalent to about 20 million yen. Yanagi donated part of the prize money to a newly formed asso ciation called the Industrial Designer's Association in Japan and used the rest of it to found The Yanagi Industrial Design Research Foundation. In our industry, foundations are rare. Yet that was how this unique foundation got its start.

Yanagi likes to design his products on a real-life scale. Instead of drawing his designs on paper, he begins with a three dimensional model. He uses clay or styrofoam to actually sculpt the design by hand, producing a design which fits perfectly to the body. This is why he has created such beautiful masterpieces like the Elephant Stool and the Butterfly stool. These cannot be created out of drawings made on paper. Yanagi not only designs his furniture in this way, but also cutlery and tableware. His technique is different from ordinary industrial designers, but the foundations of his design are full of his own originality.

Yanagi doesn't only take orders from manufacturers to design products. He actively creates products that he thinks are good and later finds a manufacturer who will agree to produce them. Many of his masterpieces were created in this way. Any freelance designer should learn this lesson from him.

There was a time when all daily use tableware was painted with a pattern or a picture. One time, Yanagi introduced a plain ceramic design to a wholesaler. The wholesaler took a look at the design and seriously asked Yanagi, "What are you going to pain on this?"

Nowadays, many wholesalers will accept that the function and beauty of a design is more valuable than what is printed on it. Yet this story took place at a time when tableware without a printed design was thought of as a half-finished product. Yanagi has been fighting to make the point clear that design is important in and of itself.

Yanagi has produced many long-time sellers. Even if a product has gone out of production, it has been reissued due to strong feedback and support from consumers. Even though 50 years have passed since his products first came out, they still look new. This may be because Yanagi always designs a product from the customer's point of view.

Yanagis designs cover a wide variety of areas. He has designed solid objects such as furniture, cutlery, cooking equipment and table ware, as well as graphic design, architecture (bridges), and the design of an Olympic torch stand.

In addition to his designs, he became curator of the Japan Folk Craft Museum in 1977. The Japanese folk movement " MINGEI" was started by his father. Yanagi Soetsu who was a philosopher. The movement is based on the belief that any product produced by the people, which aspires to be of utmost use, will result in a unique kind of beauty.

When Yanagi was young, he rebelled against his father and decid. ed to pursue a separate path. However, as he learned more about modern design, he found many similarities between them. He con- cludes as follows:

1 Functionism the beauty of use. As the function and usage of a product become refined, it will start to show its beauty.

2 A product should be designed according to the characteristics of the materials used.

3 Proper use of technique. Just as there is craftsmanship, there should be "Productsmanship".

4 Repeated production. Folk Craft refers to it as "the repeated use of hands on job is necessary for the acquisition of sureness".

5 Mass production to reduce costs.

He decided to move into the world of oil painting, because he was rebellious against his father. He even chose pure art, which his father had totally ignored. However, Yanagi was introduced to the work of Le Corbusier through Mizutani Takehiko, who had just returned to Japan after studying at Bauhaus. Yanagi decided to study French because he wanted to read a book written by Le Corbusier called "La Ville Radieuse". His French language skills came to his advantage when he was appointed as an interpreter to Charlotte Perriand. Perriand was invited by The Department of Trade at The Ministry of Business and Industry, as an advisor for exporting crafts. Ms. Perriand worked in interior and furniture design; she was a partner of the French architect, Le Corbusier, at that time.

Though Soetsu did not want his children to be the successors of his work, fifteen years after he died, Yanagi became curator of The Japanese Folk Craft Museum. No matter how hard Yanagi tried to reject his upbringing, he could not deny the fact that he had been raised with masterpieces which were carefully selected by his father. Soetsu.

Through the work of the Japanese Folk Craft Movement he has rediscovered the importance of anonymous design, which has forced him to answer the question of what the true meaning of design is.

CHAIRS

Butterfly Stool

The introduction of molded plywood along with Eames' Shell Chair has had a great influence on Japanese designers. Yanagi Sori was one of them who was counted among the most famous Japanese furniture designers. The Butterfly Stool was produced by TENDO Co., LTD.

who was very enthusiastic about learning a new technique. The chair was first introduced at the "Yanagi Sori Industrial Design Exhibition" held at Ginza Matsuya of Tokyo in 1956. At this time, Inui Saburo, a devoted technician of TENDO Co., LTD, supported the first produc- tion of the Butterfly Stool. Later Yanagi said, "if it weren't for Inui Saburo, I would not have been able to design this stool". Just as it is named, this stool has the graceful looks of a butterfly flying through the air. It is very simply made with two pieces of molded plywood connected at the seat with two bolts and one rod of steel as a stay. The manufacturing of this stool has almost become a symbol for TENDO Co., LTD. Again, the Vitra Design Museum is manufacturing and selling to the European market starting from 2005.

Elephant Stool

This stool is made of FRP. The center of the seat has an indenta- tion, the fat legs have been cut out, and the form has an appealing presence of its own. The FRP technology was introduced at almost the same time as the molded plywood. The KOTOBUKI SHOP (cur- rently KOTOBUKI) was the first to accept this technique and used it to manufacture the Elephant Stool. It represent a work of Yanagi who put importance of tactile feeling for product, showing a beautiful and soft curve, yet also being strong. It was successful only by the use of FRP. However, later Yanagi said "FRP is not a material to be use when considering ecology". After KOTOBUKI stopped its production. the Design Director of Habitat of England, Tom Dickson had decided to reproduce it with the name of "YANAGI" in 2000. From 2004, the production was transferred to the Vitra Design Museum, and still being sold with using polypropylene, much friendly material for our environment.

Stacking Chair

Molded plywood from Sapelli was used to create the organic, three-dimensional curves of the backrest and seat of the Stacking Chair. Molded plywood from Matoa was used for the frame. The chair has an overall reddish color, which looks similar to Mahogany. Recently. Yanagi has been using Mahagony a lot. The shape of this chair is very simple, almost like an anonymous chair from Northern Europe. However, this chair was released in 1998. It is a recent work of Yanagi's. He made it when he was 83 years old. It shows that he is still aggressive about making new designs. The most noticeable point of this chair is that the curves of the backrest and seat are large enough to support the legs of a seated person, yet it is still stackable and can reduce storage space. It is a masterpiece of Yanagi's which shows his attitude towards the functional aspect of his designs.

Shell Chair

This dining chair feels very light. The backrest and seat is made from one piece of molded plywood from Sapelli with steel pipes for legs. The steel pipe legs, which protrude from the center of the seat and the shell, may look insecure. However, this design is well bal- anced and looks very secure. One reason for this is obviously the design itself. But the hole near the lower back influences it quite a lot. The good design of the upper curve of the hole, which cuts upwards slightly towards the top, also makes the chair lively and modern.

Kenmochi Isamu, the second son of a military officer, descends directly from the lineage of the Date family of the Sendai Feudal Clan. At first, he had wanted to be a painter. After graduating from Tokyo Koutou Kougei (Tokyo Advanced Crafts School), he was put in charge of craft and design at the Crafts Institute in Sendai (later called as the Industrial Arts Institute). It was operated under the jurisdiction of the Chamber of Commerce and Trade which placed an special emphasis on export policy. At this institute, he met a new German architect Bruno Taut who had been invited to teach crafts- manship. It was then that he first heard of the Norm concept (mean- ing constructional planning). Kenmochi was one of the people who contributed his experiences and teachings to quickly develop the Japanese furniture industry after World War II when the Operations Arm started to build furniture and homes for their families.

After Kenmochi became an independent in 1995, the high level of activity in his work established the job category of interior designer for the first time. He was also unique in that he introduced unknown artists to new projects such as: Kayama Matazo with the first jumbo jet in Japan, and Hirayama Ikuo with a tanker "Michael Calass". He was charming and charismatic with a deep and rich sensitivity. On the evening of the opening party for the Keio Plaza Hotel, which was his final work, he decided to end his own life. In a way, I feel it was the death of his battle.

Mizunoe Tadaomi 水江忠臣 was born into a wealthy family from Oita. After graduating from the Department of Architecture at Nippon University, he started to work for the Maekawa Kunio Architecture Office. He later had to leave the office in order to serve in the military. After the War, he returned to Oita and began studying furniture design. In 1953, Maekawa asked him to join the office again. The following year, Mizunoe, along with Choh Daisaku and Matsumura Katsuo, worked on the furniture design of the International House of Japan in Roppongi, Tokyo.

Mizunoe's masterpiece was the redesign of the side chair T-0507N. His passion for this chair resulted in a beautiful design. It has been seen in the photographs of the private homes of many famous archi- tects, placed side by side with world famous masterpieces. Since he didn't work on many projects simultaneously, he concentrated all of his passion and his efforts on just one design. Even the manufacturer, TENDO Co.,LTD, lost track of which drawing was his most recent design. Mizunoe was killed in an unfortunate accident at the age of 56, yet his chairs show a high level of perfection.

Mizunoe, Choh, and Matsumura -all members of the same genera- tion- were provided with a great opportunity to build the International House of Japan in Roppongi, Tokyo. The International House was built when the house of Iwasaki the Mitsubushi Financial Organization joined funds with the Rockefeller Foundation. It was built in 1952 in order to promote cultural and scientific exchange between Japan and the international community. Nehru, the prime minister of India, and Mr. and Mrs. Walter Gropius, headmasters of Bauhaus in Germany, were among the frequent visitors.

For this project, some foreign architects residing in Japan expressed an interest in working on this project. Among them were Antonin Raymond and William M.Vories. However Murata Ryosaku, the chairman of the Art Department of the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, insisted on letting Japanese architects work on it. So Sakakura Junzo, Maekawa Kunio and Yoshimura Junzo all submitted proposals of their own. In the end, a decision was made to foster "cooperation, not competition." Because of this policy, Choh, Mizunoe, and Matsumura were all asked to design the interior.

Although Mizunoe worked on this complicated project, the only thing that Choh can remember about him is that he was always talk- ing about chairs. I, myself, cannot remember him talking about any- thing else besides chairs. For him, chairs were everything.

When Mizunoe's design was introduced in the German magazine.

"New Furniture," it was placed on a spread facing a page of Hans Wegner's design. Mizunoe was so thrilled that he wrote a letter to Wegner. Wegner not only replied to Mizunoe's letter but began a friendship with him. There are many designers who can still remem- ber Mizunoe showing Wegner's Christmas card to his friends.

Mizunoe learned about the designer's spirit from Wegner, his most respected friend. The spirit of design must peel off and polish down a design to find the simplistic beauty and elegance that is hidden beneath decoration. It is unfortunate that he left us so early. I was hoping to see the second and third redesigns of T-0507N.

Ubunji Kidokoro 城所右文次 (c. 1910–1945) was a Japanese cabinetmaker and furniture designer whose brief but influential career in the 1930s helped articulate a distinct Japanese response to international modernism by marrying indigenous materials and craft practices with the formal and structural experiments of the period. Little is recorded about his childhood and formal schooling, but by the mid-1930s Kidokoro was working as a designer and cabinetmaker associated with Mitsukoshi, Japan’s oldest department store, where a progressive furniture office sought to introduce “modern” seating and furniture for a society that had for centuries largely sat on tatami; it was in this environment that Kidokoro’s best-known work took shape.

Around 1937 Kidokoro produced his iconic cantilevered bamboo armchair for Mitsukoshi, a design that became emblematic of the store’s modern furnishing program. The chair is constructed from layered bent plywood and long vertical strips of bamboo fastened with brass studs; its arms extend into a continuous curving base and the seat slightly cantilevers so that the piece yields subtly to the sitter’s weight. This solution exploited the spring and tensile qualities of bamboo and of laminated ply, creating a lightweight yet resilient structure that read as both modern and unmistakably Japanese in material sensibility. The piece was widely exhibited and later entered important museum collections.

Kidokoro’s work is often discussed in relation to contemporaneous Western experiments with bentwood and cantilever structures, most notably the work of Alvar Aalto; Kidokoro’s 1937 bamboo armchair can be seen as a Japanese interpretation of that structural idea, but made manifest through local materials and craft processes rather than mere imitation. His approach was not to copy Western forms, but to translate the underlying structural logic into a register that drew on mingei (folk-craft) values — an emphasis on local raw materials, skilled handwork, and modest, utilitarian beauty — producing furniture that felt both international and regionally rooted.

Archival evidence and auction records show that Kidokoro’s pieces were manufactured by specialist workshops such as Chikukousha under commission from Mitsukoshi; these makers developed the layered bamboo ply and lamella bending techniques needed to realize Kidokoro’s ambitious curves. Surviving examples of his work — appearing at auction houses, dealers, and in museum acquisition catalogues — often retain factory labels or maker notations that tie them to these producers, confirming a small but significant industry in Japan at the time capable of advanced plywood and bamboo laminating techniques.

Kidokoro’s designs were shown beyond Japan, participating in the international flows of design and exhibition that characterized the 1930s. Contemporary accounts and later curatorial notes indicate that modest Japanese modern furniture, including works like Kidokoro’s, traveled with department store exhibitions and international shows that attempted to present a renewed, modern domestic aesthetic. Some sources note that works linked to Mitsukoshi and to designers such as Kidokoro were seen in exhibitions and fairs that introduced Japanese modern furniture to foreign audiences in the late 1930s. This had the double effect of placing Kidokoro’s work in a global conversation about modern living while also complicating authorship and influence when European designers such as Charlotte Perriand and others engaged with Japanese bamboo seating during their own visits and exhibitions.

Tragically, Kidokoro’s career and life were cut short by the Second World War; museum object records commonly list his dates as approximately 1910–1945, and several reference works assert that he died in 1945, a loss that prevented him from developing a larger oeuvre or from participating in the rich postwar revival of Japanese design. The scarcity of personal archives, few surviving production records, and the wartime destruction that affected many Japanese makers have all contributed to the fragmentary nature of Kidokoro’s documented biography.

Despite the brevity of his output, Kidokoro’s surviving pieces have had a long and varied afterlife: they appear in major museum collections (for example the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne and the Brooklyn Museum in New York), in design-museum retrospectives, and on the international market where specialist dealers and auction houses periodically offer original examples dating from the late 1930s. These institutions and sales catalogues provide technical descriptions (materials, dimensions, makers’ marks) that have been essential for reconstructing his methods: layered bamboo plywood bonded into lamella bends, vertical bamboo slats secured to crosspieces with brass studs, and the deliberate use of cantilevering to create a responsive seat.

Stylistically, Kidokoro stands at an important crossroads in Japanese design history: he demonstrates how local craftspeople absorbed and reformulated modernist formal ideas while preserving the primacy of indigenous materials and making techniques. His chairs are warm, tactile, and deceptively complex — they demand a high level of joinery and lamination skill and reveal an aesthetic that privileges structural honesty and the visible logic of construction. Because his surviving works are both technically interesting and visually compelling, scholars and curators often use Kidokoro as a case study when discussing prewar Japanese furniture that anticipated the postwar global interest in Japanese modern design.

From a practical, object-level standpoint, the condition reports and auction notes for Kidokoro’s chairs teach us about the material vulnerabilities of bamboo ply: hairline cracks at edges, separation at seams, varnish crazing and loss — all aging characteristics that require sensitive conservation. Such technical details underline the care required to preserve this type of furniture and also explain why original pieces are relatively rare on the market and prized by collectors. Major sales and catalogues (Sotheby’s, specialist dealers, and curated showrooms) provide photographic records and provenance notes that have helped re-introduce Kidokoro’s name to contemporary collectors and museums.

Today, Ubunji Kidokoro is remembered less as a prolific designer than as a seminal figure whose inventive use of bamboo and plywood in the late 1930s opened a dialog between craft and modernity in Japan. His surviving chairs function as physical testimonies to an era when Japanese designers and department stores experimented boldly with new domestic forms, and they continue to be studied, conserved, exhibited, and occasionally sold, ensuring that Kidokoro’s experimental fusion of material, craft, and modern structural thinking remains part of the broader story of twentieth-century design.