Side Gallery

Side Gallery

WishlistFollow

Follow

Born in 1911, Riki Watanabe 渡辺 力 was considered one of the pioneers of post-war Japanese design. After graduating from the Woodcraft Department at Tokyo Higher School of Arts and Design (currently Chiba University), Riki Watanabe joined architect Bruno Taut's office in Gunma in 1936. In 1949, he established his own design studio, and quickly won recognition for his low-cost String Chair in 1952. His Torii Stool and Circular Center Table won the Gold Medal at the Triennale di Milano in 1957. In addition to interior and furniture design Watanabe also designed clocks and watches.

Furniture as Organ - Design of Riki Watanabe by Hitomi Kitamura

Riki Watanabe (1911-) has, in the over half a century since 1949, when he opened his design office and became an independent designer, been one of Japan's leading designers, with a continuous record of achievement, particularly in the fields of interior and product design. Over these decades, he has also been a founding member of such prominent design organizations as the Japan Industrial Designers' Association (JIDA), the Japan Design Committee, and the Craft Center Japan. Watanabe has been, in fact, a driving force behind the design movement that flourished after the war. Moreover, he is still active as a designer, unveiling, for example, a new wristwatch design this year. In this essay, I would like to explore the thinking that underpins his long career in design, using the concept of the organ as a key element.

From dishes and vases for use in daily life to magazine covers, in the area of graphic design, Watanabe has turned his hand to designing in a wide range of fields. His home territory has always been, however, the design of furniture and, by extension, interior design, as both the works in this exhibition and his educational background indicate. (He studied design in the woodcraft department of Tokyo Higher School of Art and Design, which was headed by Joichi Kogure (1882-1943) and produced a stream of important furniture designers, including Katsuhei Toyoguchi (1905-1990) and Isamu Kenmochi (1912-1971).)

As the title indicates, in this essay, I liken Watanabe's furniture designs to organs. Please note, however, that I am not trying to make a connection between his work and forms that might be called to mind by the word "organic." Rather, by the term "organ" I would like to invoke the way the various organs in the human body fulfill their specific physiological functions. They are independent in form, yet coordinate and harmonize in the body as a whole. Considering that relationship may be an aid to understanding Watanabe's designs.

If one compares the body enclosing those organs to a built structure, then the furniture within it would correspond to the organs such as the heart and lungs. The lungs handle respiration, the heart is in charge of the circulation of the blood, and their forms diverge, because the work they perform is different. Similarly, it is not strange at all that pieces of furniture required in various aspects of daily life, including resting, eating, and working, should vary in form to make for more comfortable (and at times more efficient) living. Let's take chairs as an example. For work mainly performed standing up, the need is for a dynamic chair from which the user can immediately shift from lightly resting his or her weight on the seat to standing up: a tall backless stool, for example. For light work, a chair with a broad, relatively deep seat and a straight back is desirable, while a chair for extended work at a desk calls for one in which the hips are firmly, stably seated and the back can stretch back. The categorization of chairs by types of work was an issue addressed early in the homes of young architects who sought new living spaces after the war. From the furniture design perspective, we find a similar classification in an article entitled "How to use furniture" in the October, 1953, issue of Modern Living (published by Fujin Gaho-sha), a magazine for which Watanabe also provided editorial cooperation.

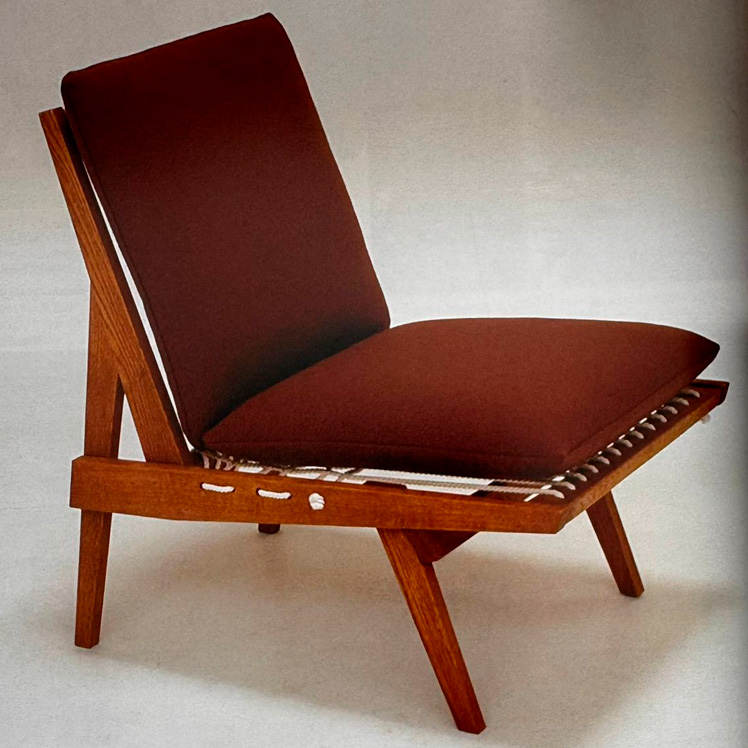

As that background suggests, Watanabe's furniture was designed in the context of a thorough awareness of, above all, what was needed where within living spaces. Let us, for example, consider one of his best-known works, Rope Chair (Cat. no.3) from this perspective. Since it has a broad and deep seat, for sitting back deeply, and the back is at a slight angle, it can be understood as a classic example of a chair for rest and repose, in which one can lean back and relax. It is also noteworthy that this chair springs from a close connection with the residential environment in Japan at the time he announced the design, in the early 1950s. It assumed the use of zabuton, the large, square floor cushions which would be found in any Japanese home for sitting on tatami, as chair cushions. The Rope Chair design thus made the chair, which was not commonplace in ordinary households at that point, much easier to incorporate into home life. The design critic Masaru Katsumi (1909-1983) spoke of Rope Chair with two overlapping images: "the ingenious framing of a Japanese ship, the beautiful structure of a hand loom." He gave it high marks as a design that, from the aspect of form as well, brilliantly fuses the chair, which originated in the West, with Japanese living spaces.

If furniture forms do follow their functions in carrying out the actions required in the course of daily life, then of course their forms will differ, depending on how they are to be used. But while diversity in form is fundamental to furniture, individual pieces should not fail to be in harmony with the spaces around them. "When looking at a chair, one can imagine the living space in which it would be placed and used," as Watanabe wrote. That comment must be read in terms of an attitude towards design consistently rooted in utility and extended to spaces limited to a particular time or region. Pieces of furniture are, to him, functional physical structures that compose living spaces while performing clear-cut roles within them and that mediate between human beings and the architectural spaces around them. Watanabe's furniture designs thus faithfully fulfill the functions demanded of them while also realizing his thinking in simple, almost ascetic forms predicated on productivity as well.

Watanabe's view of design, which perceived furniture as the units composing living spaces and worked out from there to expand design into other areas, was the result of his basic orientation to design in the woodcraft department of Tokyo Higher School, which he entered in 1933 and where he received his basic education in design. A view of design and related thinking similar to Watanabe's are presented in the book Jutaku (Housing; Kozosha, 1930), by Shigeji Nomura (1901-1967). Nomura, a graduate of the architecture department of Kyoto Imperial University, had studied with Koji Fujii (1888-1938), the architect who created the famed Chochikukyo (1929), a masterpiece among experimental dwellings. From 1927 on, apart from a period during which he studied abroad in Europe, Nomura taught at Tokyo Higher School, in the woodcraft department.

Watanabe later recalled Nomura's thinking as follows: "In his lectures, he constantly harped on the idea that architecture should expand from the inside out, like blowing up a balloon. The shapes of furniture are determined by human actions in the course of living, and then that expands out to interiors and then to structures." Those ideas are developed in Nomura's book Jutaku. Seeking the starting point of residential design in the behavior patterns associated with rest and repose, he called for taking the postures of rest and repose as the basis for design and gradually extrapolating from them to architectural spaces-windows, floor, walls. In that book, Nomura constantly quoted Le Corbusier, particularly his argument that the plan develops from the interior to the exterior-"The exterior is a result of the interiors- so much so that one might think that his reading of Le Corbusier's Towards a New Architecture (1923) was the source of his ideas on the resting posture as the starting point in residential design.

Nomura, however, merely quoted Le Corbusier to reinforce his argument, having developed his theory of the posture of rest and repose as the point of departure on his own. He listed the three necessities of human existence as "activity, rest, and nourishment." It is fascinating that of those, he fixed upon rest (or rest and repose) as the starting point for domestic design and architecture. At about the time his book was published, in the 1920s and early 1930s, a major drive to introduce the chair to residences-chairs had already been incorporated in a wide range of other spaces, including schools and offices-was underway. We can well imagine that, having developed the theoretical underpinnings for why chairs should be part of home life from his examination of humans in physiological terms, he roused the furniture designers studying at the Higher School-including most notably Watanabe- to act on that argument.

We can also see Nomura's distinctive development of this line of thought in his consciously formulating the argument, while asserting the virtue of resting in chairs, in terms of the need to make chairs harmonize naturally with existing Japanese lifestyles. He avoided specifying which style of rest was more desirable, sitting in chairs or on tatami covered floors, as Japanese were accustomed to; instead, he proposed low chairs with their seats near the floor, for the coexistence of both types. Clearly that thinking is strongly linked to Watanabe's Rope Chair. Tracing its history, we find it was the result of critically succeeding to, and deepening, the efforts to modernize housing in terms of Japanese tradition made by the previous generation, including Koji Fujii and Joichi Kogure. Those earlier housing reformers, especially Fujii, had sought to reinterpret the sukiya-style house (with its tatami and tokonoma, simplicity, and use of natural wood; the classic example is the Shoin of the Katsura Detached Palace) in terms of a modern design sensibility. To understand that legacy, let us refer to the statements that Joichi Kogure made in his Wagaya wo kairyo shite (Improving the home; Hakubunkan, 1930). Kogure is significant here because Watanabe and he partook of the same attitude towards design, transmitted to Watanabe by his teacher at the Higher School, Nomura.

Kogure's book begins with a chapter entitled "Towards a modern chair-style lifestyle." He wrote to provide suggestions for making gradual improvements in domestic equipment and styles that would be appropriate for modern times, through introducing the chair, already part of government and corporate offices, to the home. The part of his argument calling for clearly separating rooms by use, for dining, socializing, sleeping, and cooking, based on notions of sanitation and efficiency, was an assertion in concert with the housing reform movement, which the government was actively promoting at the time. That assumed a fundamentally different lifestyle from the traditional Japanese style based on tatami-floored rooms, in which the same room was used for eating and sleeping.

What is particularly interesting about Kogure's book is that he regarded modernizing lifestyles as inevitable, in order to "focus on perfectly achieving total efficiency in living, eliminating waste in the home." But he was not urging that lifestyles be Westernized at a single bound: "It would be absolutely unforgivable thoughtlessly to abandon the beauty of the traditional." His thrust was to retain the beautiful strong points of the Japanese house while incorporating the advantages of Western-style housing to make up for the disadvantages of Japanese dwellings, and thus gradually improve lifestyles. But what Kogure sought went beyond the literal meaning of improvement as correcting defects. His thinking was, perhaps inevitably, more transformational. That tendency appears in passages such as the following, in which he argues for furniture that meets tradition half way in introducing a chair-based lifestyle, in which the effort to improve furniture would be a first step: Incorporating chair-based furniture into conventional Japanese rooms will make life more convenient while achieving a beautiful harmony in the room as a whole. But unless we make quite radical improvements in it, furniture as it is found today will be inconvenient hindrances in daily life that will also make rooms look utterly ugly and, in the end, will prevent achieving the goal of converting to a chair-based lifestyle.

Then, after a discussion of the dimensions of furniture that would fit Japanese rooms and of chair types, Kogure concludes as follows:

Furniture that will meet the crucial needs of the new age and yet that can harmonize with our Japanese rooms: such improvements will not produce satisfying results if they amount to nothing more than a repetition of the styles and production methods of the past. What is most necessary, in this age, is to search out methods for making the most important, essential improvements, in line with the needs of contemporary home life, to have all designs flow from the same fundamental principles, and to seek a single consistent style worthy of repetition."

Kogure's stated position remained uncompromisingly in favor of improving existing lifestyles, but the substance of his argument was his felt need for the creation of furniture suitable for Japanese residences. In fact, considerable creativity would be required to introduce that new style, because it was so removed from conventional Japanese lifestyles. While explicitly affirming, not rejecting, the status quo, he was trying to revolutionize lifestyles in the spirit of logic and efficiency. Kogure's position therefore provided for acceptance of creativity in furniture design. What he shared, fundamentally, with the other early modernizers addressing furniture and housing styles was a commitment to creating new forms in ways that harmonized with the status quo.

I would also like to quote a passage in which Kogure speaks specifically about improving furniture: Furniture, like structures, is not just to be seen. The most important conditions a piece of furniture must meet are convenience in use in daily life and appropriateness for its intended use, based on the way people actually live. The materials must suit the purpose, be handled without waste, and be used to create a rational and durable structure. Moreover, the work should be pleasing to the human user-light in weight, smooth to the touch, beautiful in appearance, and richly fresh and innovative. It should also be inexpensive. These important qualities are utterly essential in contemporary home furnishings."

The Kogure doctrine of improving (or, rather, creating) furniture based on actual lifestyles and predicated on utility we see realized in Watanabe's Rope Chair. It achieved low cost by using the zabuton to be found in every home for its cushions and had its seat placed low to fit into Japanese living spaces and accommodate the habits of Japanese used to a sitting-on-the-tatami lifestyle.

After graduating from the Higher School, Watanabe joined the Gunma Industria Center, with which Bruno Taut (1880-1938) was then associated, worked at Miratiss, a store that was opened on the Ginza to sell Taut's craft products, and had an opportunity for contact with Taut during his stay in Japan. It was a great benefit to him, while he was still seeking his own understanding of what modern design was, to have actual contact not only with Taut and his work but also with other Western designers, such as Antonin Raymond (1888-1976), and their work as well. Joichi Kogure then called Watanabe back to the polytechnic to serve as an assistant professor. With the outbreak of World War II in the Pacific, however, Watanabe's exploration of design was temporarily interrupted. Nonetheless, work from 1942, while he was teaching (Cat. no.1), was finished in simple, undecorated forms that were a distillation of the formative vocabulary of modern design. Clearly, his design orientation was solidly set.

After the war, in 1949, Watanabe opened his independent design office and began his career as a designer. In 1951, his Laminated Fumiture received the New Structure Award at the Shinseisaku Exhibition. After that auspicious beginning, he went on to submit his Rope Chair to the first full-fledged design competition in Japan, the New Japanese Industrial Design Exhibition, and solidified his footing as a furniture designer who was attracting considerable attention for his inexpensive furniture for the living room. In addition to producing that work, he was working collaboratively with the young architects Kiyoshi Seike (1918-2005) and Kenji Hirose (1922-) on residential furniture and making a noteworthy contribution to the creation of modern residential spaces. Together, in the early 1950s, they designed open residential spaces based on the single room concept and played leading roles in housing reform. Placing furniture in those open interiors demarcated spaces and clarified functions, giving their spaces the functions required of dwellings. Through his work in the 1950s, we can see Watanabe clearly indicating that furniture should function as organs within the dwelling body.

Subsequently, as Japanese society put systems for mass production in place, his designs began developing in multifaceted ways. The Riki Bench (1960, Cat. no.11), designed for use in public buildings and used today in museums and many other public facilities, his furniture using corrugated paper (1965, Cat. no.13), and a series of clocks, beginning with one with a digital display (from 1964 on) suggest the richness of his design imagination. In all this work, Watanabe has demonstrated a consistent commitment to creating the designs that are needed in residential spaces as they change with the times.

Crosscutting the variety of materials and design domains in which he works is his penetrating awareness of the spaces in which objects are used. What connects his designs, in all their diversity and broad range, is the approach to design that is his legacy from studying at Tokyo Higher School of Arts and Design. Joichi Kogure, who proclaimed the need for new furniture appropriate for Japanese residential spaces with the introduction of a chair-based lifestyle, Shigeji Nomura, whose point of departure in thinking about Japanese residential spaces was the posture of rest and repose and connected those idea to architecture: that receptivity to modern design in Japan is the heritage that inspires Watanabe's design practice.

Trying to trace Watanabe's path while focusing on the Tokyo Higher School, one begins to think that the chair was inevitably the heart of the residential spaces that he took as his starting point. In this exhibition, given the centrality of the chair in our understanding of Watanabe, we have decided to introduce primarily his furniture designs. That is also why there are so many chairs among the objects exhibited. But do understand that this exhibition does not begin to introduce the whole of Watanabe's work.

Perhaps the largest lacuna concerns his critical activity, which accounts for a not insignificant part of his work; this exhibition does not address it at all. Watanabe, writing anonymously, produced articles introducing such designers as Raymond Loewy (1893-1986) and Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988), under the title "American Industrial Design," for the magazine Shinkenchiku (lit. New architecture), but that is only a start. He actively wrote about what was happening in design in many other countries and did everything he could to educate about design.

His engagement with the Craft Center Japan is also important. The stimulus for founding of the center was the arrival in Japan of the Nordic designer Kaj Franck (1911-1989). It was set up with the aims of preserving and promoting the living handicraft traditions of Japan. As one of the founding members, Watanabe addressed the question of how to make effective use of Japan's craft traditions in design; one glimpse of the vibrant approach to solutions he took was his rattan stool. While one had expected further variations of it would appear, no other surviving works have been discovered. I will leave the question of what happened to them as a topic for future discussion in concluding this essay.

Hitomi Kitamura is Curator of Crafts Department at The National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo.

ENQUIRE ABOUT THE DESIGNER