Side Gallery

Side Gallery

WishlistFollow

UNO

BARCELONA

SIDE GALLERY

OCT 14 2015 - FEB 12 2016

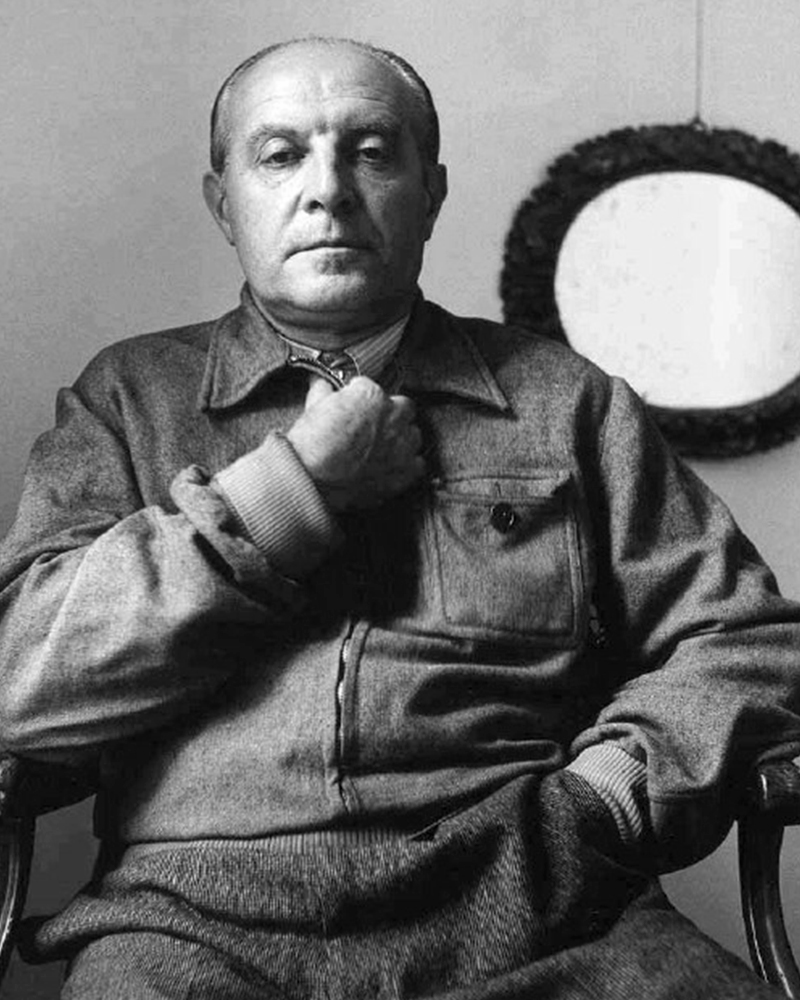

Side Gallery was established in Barcelona and founded in November 2015. The exhibition UNO was the gallery’s inaugural exhibition. The show mixed a combination of international design of the twentieth century, as well as contemporary design, focusing on historical design from Latin America and Italy, primarily concentrating on the work of designers Lina Bo Bardi and Gio Ponti, exploring their inter-relationship and their processes of creation, when back in the forties a young Lina Bo Bardi joined the Gio Ponti Studio who was already a star architect and a well known publisher through his work in Domus Magazine, whose influence on modern Italian architecture is incontestable. The combination of these two designers’ masters of lightness and material production revealed Side Gallery’s taste for iconic design.

"The show mixed a combination of international design of the twentieth century, as well as contemporary design"

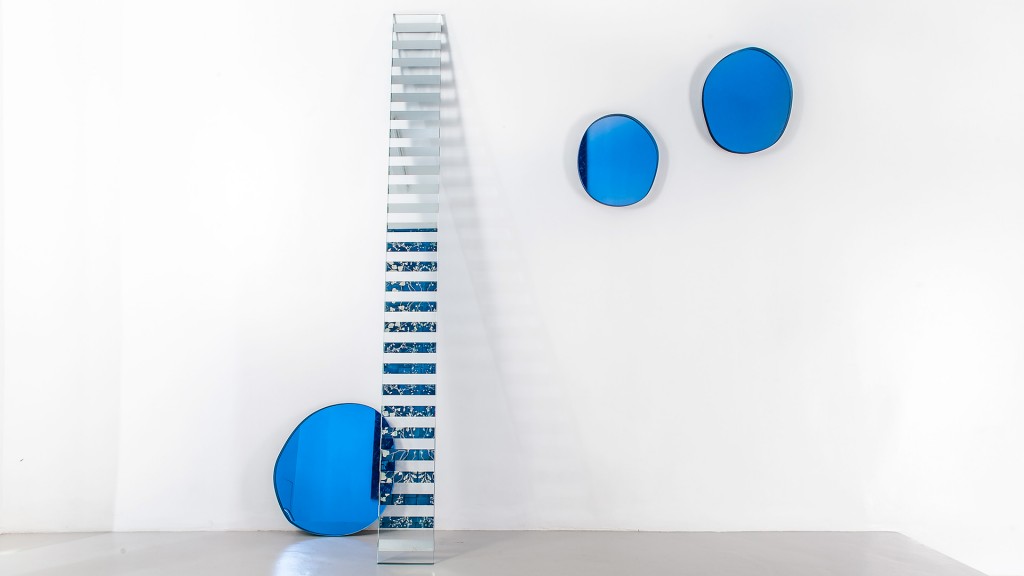

In the gallery exhibition UNO, the work “Seeing Glass” by artist Sabine Marcelis was of particular interest. The gallery tried to approach to a new generation of designers in order to promote and explore new sensations of the design world, focusing on the investigation of materials, forms and techniques. The Seeing Glass series made in collaboration with Brit van Nerven looked haphazard because of their hand-drawn shape, but also futuristic thanks to a spectacular gradient surface, a complex effect created by using multiple layers of glass, mirror, and foil.

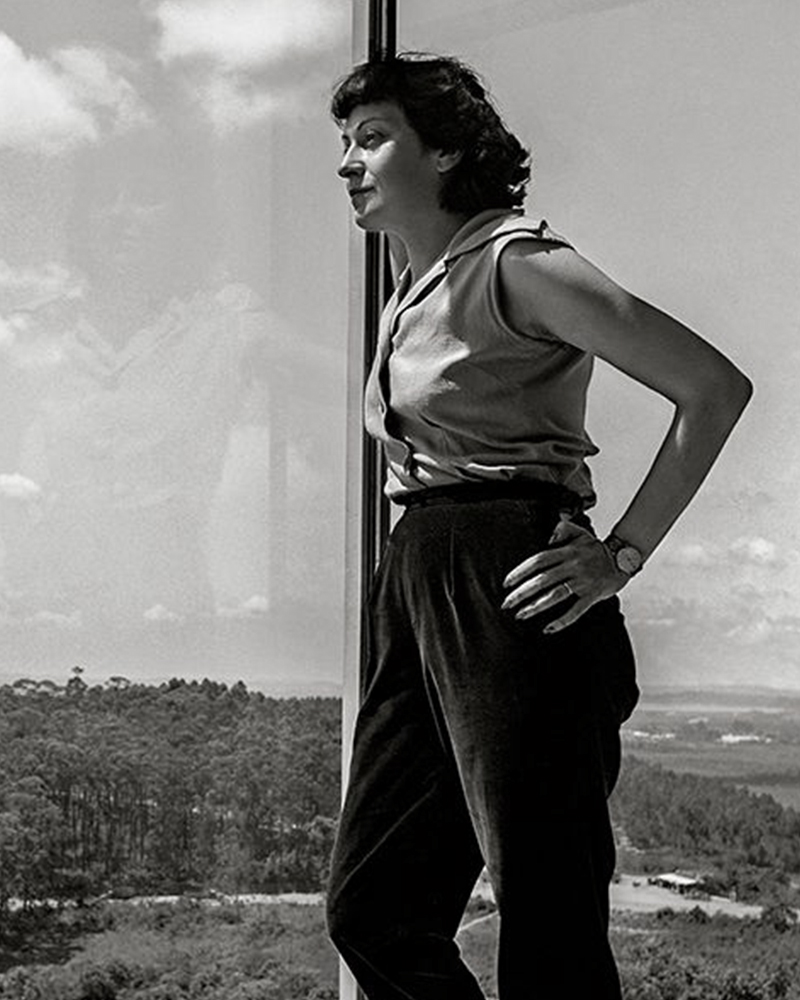

Achillina Bo, best know as Lina Bo Bardi, (born December 5, 1914, Rome, Italy—died March 29, 1992, São Paulo, Brazil), was an Italian-born Brazilian Modernist architect, industrial designer, historic preservationist, journalist, and activist whose work broke free from convention. She designed daring, distinctive structures that merged Modernism with populism.

Bo Bardi graduated with an architecture degree in 1939 at the University of Rome, where she had studied under architects such as Marcello Piacentini and Gustavo Giovannoni. Upon graduating, Bo Bardi moved to Milan and began working with the architect Carlo Pagani as a design journalist. She also worked with the famous architect and designer Gio Ponti and collaborated with him on the magazine Lo Stile, while contributing to several other Italian design publications. In 1944 she became deputy director of Domus, the acclaimed design magazine established by Gio Ponti in 1928, and retained the post until 1945. In 1945 Domus commissioned Bo Bardi, Pagani, and photographer Federico Patellani to travel through Italy documenting the destruction of World War II. Later that year, she collaborated with Pagani and art critic Bruno Zevi on the short-lived magazine A – Attualità, Architettura, Abitazione, Arte, which published their judgments and verdicts discussed ideas for restoration of the postwar devastation.

Pietro Maria Bardi, an art gallery director, dealer, and critic, became her husband in 1946. Pietro was soon invited to Brazil by the media tycoon Assis Chateaubriand to help coordinate the Art Museum of São Paulo (Museu de Arte de São Paulo; MASP). The couple, as a result, emigrated across the Atlantic to the modernist hotspot Sao Paulo.

Bo Bardi designed the interior and the museum fittings for the first iteration of MASP, which opened in 1947. She developed an innovative system for suspending paintings away from the wall. (Her design was torn down in the 1990s and replaced with a conventional wall hanging system.) She also designed folding stackable chairs made from Brazilian jacaranda wood and leather intended for use at lectures and museum events. Later in life, she curated an exhibition at the museum on the history of chair design.

In 1950 Bo Bardi founded the magazine Habitat with her husband and worked as the editor until 1953. During that time, it was the most influential architectural magazine in Brazil. She became a citizen of Brazil (1951) and started the country's first industrial design course at the Institute of Contemporary Art (a part of the expanded MASP). She designed for her and her husband, the notorious Modernist Le Corbusier, influenced Casa de Vidro (Glass House) in the Morumbi neighborhood of São Paulo. Constructed on a hill, Casa de Vidro, over time, integrated into the landscape entirely. The front of the house extended out over the slope of the hill, elevated and supported on delicate-looking stilts. In 1951 she also designed her most famous piece of furniture, Bardi's Bowl, a chair in the form of an adjustable hemispherical bowl resting in a steel cradle.

By the mid-1950s, it was clear that MASP had outgrown its original building, with galleries and dedicated spaces for teaching art. By the 1950s, the popularity of MASP overcame the museum's physical capacity. In 1958 Bo Bardi was commissioned to design the new building. The building stands today as her most dominant creation. Located on São Paulo's Paulista Avenue, Bo Bardi's iconic glass-and-concrete building was elevated 8 meters (26.2 feet) above the ground on sizeable red pillars. The space at ground level provides a shaded heaven away from the hot summer sun and a gathering place for concerts, protests, and socializing.

In the late 1950s Bo Bardi began an extended period of living and working in Salvador, a poor city rich in cultural heritage in the northeastern state of Bahia. She gave several lectures at Bahia University's School of Fine Arts in 1958, and in 1959 she was invited to create and run Bahia's Museum of Modern Art (Museu de Arte Moderna da Bahia). She chose to house the museum in the Solar do Unhão, a former salt mill and part of a network of historic seaside constructions that she restored in 1963. Bo Bardi added a museum of popular art and an art school to the Museum of Modern Art, all under the roof of Unhão.

However, political unrest forced Bo Bardi to leave Bahia in 1964. Her return to São Paulo marked the beginning of Brazil's lengthy era of oppression under a military dictatorship that lasted until 1985. During that period, Bo Bardi curated exhibitions and worked in theatre, designing sets and costumes for several productions, notably a 1969 production of Im Dickicht der Städte (In the Jungle of Cities), an early play by Bertolt Brecht.

Bo Bardi's time in Bahia altered her political and aesthetic philosophies. The region's language and historic architecture led her to adopt a design process guided by social and ethical responsibility and inspired by allegiance to her adopted country and its native aesthetic traditions. Bo Bardi dedicated herself to creating only Brazilian architecture, projecting simple designs, and sourcing local materials, the style of architecture she called "Arquitetura Povera" ("poor", or, "simple" architecture). Since her initial experience in Salvador, much of her work involved re-designing and developing existing structures and restoring and preserving historic buildings. Throughout the 1980s Bo Bardi led preservation and restoration projects in the historic center of Salvador, including the House of Benin, which houses an art collection, as well as Misericórdia Hill, an extremely steep historic street (both in 1987). Her next major architecture project was the SESC Pompéia (built in stages, 1977–1986), a leisure and cultural center in São Paulo sponsored by the nonprofit Social Service of Commerce (Serviço Social do Comércio). Bo Bardi converted an old steel drum factory into a center for various facilities; sports, theatre, and other leisure activities.

Bo Bardi, although late, has been given her due as one of the most prolific women architects of the 20th century. In the mid-1980s, working alongside the architects André Vainer and Marcelo Carvalho Ferraz, Bo Bardi designed an addition to the Glass House, the Instituto Lina Bo e P.M Bardi (originally the Instituo Quadrante). As well as housing Bo Bardi's archive, The Instituto Lina Bo e P.M Bardi is an exhibition space dedicated to the study of Brazilian art and architecture.

In 2012, the centennial of her birth, Bo Bardi's career was celebrated with the launch of a limited-edition line of her bowl chair, a major traveling retrospective organized by the British Council in London, and the publication of a scholarly monograph discloses her life's work.

Sabine Marcelis (b.1985 New Zealand) is a designer living and working in Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Raised in New Zealand, she was recognized from a young age for her design abilities, being awarded the New Zealand Young Designer of the Year. Marcelis studied industrial design for two years at Victoria University in Wellington, and continued her studies at the Design Academy Eindhoven, where she graduated in 2011. When graduating the designer was nominated for a fleet of prestigious design grants, such as the ‘Unge Talenter Designpriser’ by the Norsk Designråd, the René Smeets Award, and the Keep an Eye Grant.

Since graduating, she has been operating Studio Sabine Marcelis, working within the fields of product, installation and spatial design with a strong focus on materiality. Her work is characterized by pure forms and natural elements such as the reflections of light and water, which she believes highlight material properties. Growing up in New Zealand Sabine was surrounded by dramatic landscapes, always sensitive to the light of the sky, the ocean and the snow on the mountains, the artist was inspired by the communication of the natural elements. Her work captures these beautiful moments in nature on a smaller scale, as objects or installations.

Over the last decade, the award-winning designer has become known for her work with resin and glass. Her receptiveness for these two materials is due to their manipulability; sharp angular shapes as well as spineless curves can be protracted giving the artist endless scope for form. Moreover, the translucency of the both materials can be adjusted from sheer transparency to milky or solid opaque finishes. Working in collaboration with industry specialists, Marcelis intervenes in the manufacturing processes using material research and experimentation to achieve new and surprising visual effects, applying a strong aesthetic point of you to the material development processes. The series Candy Cubes is an example of the designer’s complex material investigation; a polyester resin mold is used to cast the piece, followed by an intensive polishing process. The cast resin is light sensitive, as sun rays shine down onto the solid blocks, the light illuminates the edges, sugar coating the sides, making the aptly named “marshmallow” colored candy cube appear edible.

As well as playing with natural light, Marcelis also experiments with artificial lighting in her work. The introduction of neon light to her material combinations expresses the relationship between light, color and transparency in a more constant context. In 2015 Marcelis produced the series Dawn Light whereby the introduction of a white neon tube to a series of different geometric resin objects was used to reflect a unique moment in nature; when the sun, clouds and sky all join together, creating a momentary riot of hues. The series was on show at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Holland. Since then Marcelis has continued to work with neon and resin developing complex colour recipes and finishes, resulting in her Totem Series commissioned and sold exclusively by Side Gallery in 2019. The collection is composed of four different sized lighting elements, two table and two standing lamps. The Totems are built with several stacked translucent resin volumes which are slightly rotated on a central axis. The carved-out void where the neon light is inserted allows for a multifaceted play between the twisted planes of polished resin and light reflections. Every angle of the lights is a unique visual experience.

As well as designing object pieces, the Dutch designer has a series of impressive installation projects associated with her profile including, the Aesop Vedovelle Fountain, the Dutch Pavilion at Cannes Film festival 2017, a Light installation at Biennale Interieur 2018, The Solo Sun Dial project 2018, Burberry x OC in 2018 and De/Coding ‘Alcantara in the tapestry Rooms’ in 2019. Perhaps her most famous installation was her Shapes of Water or Fendi Fountains installation, first exhibited at Design Miami 2018. The ten water sculptures designed from cast resin were a continuation of Marcelis experience and experimentation in material practices, projecting her own vision her elegant avant-garde creativity corresponded directly with the Fendi philosophy.

The designers most prestigious exhibition yet, was her museum show “NO FEAR OF GLASS” in December 2019. The intervention commissioned by Side Gallery in collaboration with the Mies Van de Rohe Foundation, consisted of five original works by the Dutch designer, meticulously placed within the Pavilion. The five pieces were designed to extrude from the architecture itself; two large chaise lounges were pulled up from the ground by extending the travertine floor to form a base, they were sliced with a singular sheet of curved glass which was seemingly pulled from the walls. The two materials met and became sculptural yet functional furniture pieces. Eight chrome columns provide the structural support for the roof of the pavilion. Marcelis introduced a ninth mirrored-glass column which functioned as a light and was placed in line with the structural columns, blending in seamlessly with the architecture, both in form and materiality. In the water pond outside the pavilion, a curved glass fountain could be seen bending the water upwards from the ground, and letting it spill over and back down.

Marcelis won the 2020 Wallpaper Designer of Year Award, her material exploration continues to create surprising applications as her reputations reaches all corners of the world. The designer continues to be represented by Side Gallery where a number of her pieces can be seen, including the series, Voie Lights, Seeing Glass, Filter lights, Totem Lights, Candy Cubes and others.

Giovanni "Gio" Ponti (born November 18, 1891, Milan, Italy–died September 16, 1979, Milan, Italy) is considered one of the most important and influential Italian architects. He was successful as an architect, industrial designer, furniture designer, artist, and publisher. His influence on modern Italian architecture is incontestable, and he is often referred to as the father of modern Italian design.

He worked in the design profession for over sixty years. During his prolific career, Gio Ponti produced several furniture pieces, decorative artworks, and industrial product designs, extracting old artisan skills while exploring modern production techniques. Additionally, creating critical architectural works in Italy and internationally.

The great designer graduated from Politecnico di Milano in 1921. In 1923, he began working in industrial design, designing ceramics for the Richard Ginori pottery factory near Florence. After two years, he convinced Richard Ginori to participate in the Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (a 1925 Paris exposition), where Ponti's ceramic designs were very successful. During this time, Ponti forged a lasting relationship with the executive and shareholder of Christofle, Tony Bouilhet, who later in life would marry Ponti's niece, and for whom he designed Villa Bouilhet at the Saint-Cloud golf club near Paris, one of Ponti's first housing design projects. During his 15-year association with the Richard Ginori pottery factory, but especially during the early years, Gio Ponti collaborated with craftsmen and artisans to create rich designs with abundant colours, elegant shapes, and skilled craftsmanship, mainly in the neoclassical style. This style was out of favor with the functional and minimal approach of the then-prevalent Italian Rationalism, and it was distinctly present in Ponti's work in the 1930s and 1940s and less and less so in the later years.

In 1928, Ponti delved deep into publishing and began Domus, architecture and design magazine, to energize and assimilate Italian architecture, interior design, and decorative arts. His leadership at Domus would allow him to express his ideas regarding the Novecento artistic movement, a counter-movement to Rationalism, and ensure recognition of top Italian design. He worked at Domus until 1941, when he moved on and founded Stile magazine (Lo Stile–Nella casa e nell'arrendamento), and asked several young architects and critics–among them Lina Bo Bardi, to collaborate with him. However, Ponti closed Lo Stile and returned to Domus in 1947, where he remained involved for the rest of his life.

Many books, magazine articles, and exhibitions have been attributed to exploring the influence and exceptionality of Gio Ponti's work. Throughout his working life, he designed a considerable amount of ceramics, furnishings, and objects. He embarked on many of his designs alone, and some were created in collaboration with other artists and designers of the time. He produced some of the objects himself, while others were made in workshops by expert craftsmen, and some pieces were manufactured by some of the significant furniture manufacturing companies of the time. The diversified production of his work is a clear indicator of his interest in both industrial productions and artisanal production.

In 1923, Ponti made his public debut as a product designer in Italy at the first Biennial Exhibition of the Decorative Arts in Monza, followed by his involvement in organizing the subsequent Triennale exhibitions of Monza and Milan. In 1933, Ponti exposed entrepreneurial spirit and invited Pietro Chiesa to join him and Luigi Fontana to embark on the venture of Fontana Arte, a company that would become a force in Italian furniture design that specialized in manufacturing furniture, lighting, and furnishing accessories.

In the 1940s, Ponti collaborated with Paolo de Poli to produce furniture, decorative panels, and new objects of design and animal motifs in sculptural forms, and in 1946, he started three years of involvement designing Murano glassware for Venini.

During the early 1930s, Gio Ponti and Piero Fornasetti started a long, productive, and somewhat methodic collaboration, as it mainly consisted of Ponti-designed furniture decorated with Fornasetti paintings and engravings. During the 1950s, in line with the other influential Italian designers, such as Nino Zoncada, Gustavo Pulitzer, Paolo de Poli, Pietro Chiesa, and Gino Sarfatti, Ponti designed the interiors, including the furniture for ocean liners. In 1947, Gio Ponti established a long and strong friendship with the Italian architect and designer Ico Parisi and his wife, Luisa Aiani, collaborating in the design studio La Ruota.

In the late 1940s and 1950s, Ponti became a bountiful furniture designer, his chairs and sofas of significant popularity. His work was portrayed with a joyful spirit and a sensitivity to modernism that are persistent. Among his important chair designs are the armchair model no. 811 for Figli di Amedeo Cassina (1950), with an inclined and angular wooden frame and a suspension system for the seat and backrest made out of elastic belts made by Pirelli; the Model 111, also for Figli di Amedeo Cassina (1950); the Diamond sofa, originally made for his house (Cassina,1953); the Mariposa, or butterfly, chair, which was originally designed for the Villa Planchart in Caracas (1955); the successfully omnipresent Superleggera chair, also for Cassina (1957), the crowning achievement of a long and fruitful work relationship designing furniture and objects for Cassina; the Continuum rattan chair for Pierantonio Bonacina (1963); the Dezza armchair for Poltrona Frau in 1966; and the Gabriela chair, or the Sedia di poco sedile, for Pallucco (1971).

Other important Ponti designs for Italian furniture manufacturers include

the series of chairs, lounges, desk chairs, and desks designed in 1950 for the Vembi-Burroughs office in Genoa;

the designs of cabinets and sideboards for Singer & Sons (1951);

the vanity desk or vanity dressing table for Giordano Chiesa (1951);

the side table D 5551 designed initially for his house in Via Dezza in Milan (1954);

the 1960 and 1964 furnishings for the hotels Parco del Principe in Rome and Parco del Principe in Sorrento; and

many furniture pieces he designed in the late 1960s for Tecno, Osvaldo Borsani's furniture manufacturing company.

Gio Ponti participated in the architectural and interior design of two important hotels in Italy: the Hotel Parco Dei Principe in Sorrento (1960) and the Hotel Parco Dei Principe in Roma (1964). The interiors for these two hotels were designed with a unique modern sensuality that evoked sophistication and style. The projects were created in collaboration with Fausto Melotti and Ico Parisi.

In 1966, he invited lighting designer Elio Martinelli to showcase his lamps at the opening of the Eurodomus exhibition, which drove forward Martinelli's career as an innovative light designer.

Among Ponti's architectural masterpieces of the 1930s are the Institute of Mathematics at the University of Rome (1934), the Catholic Press Exhibition in Vatican City (1936), and the first office block of the Montecatini company in Milan (1936). In 1950, Alberto Pirelli, the owner of the Pirelli tire company, selected Gio Ponti to design and develop a building to house his company's offices. Gio Ponti hired architects Pier Luigi Nervi and Arturo Danusso to collaborate with him, and the team began the construction of the Pirelli Tower in 1956. When completed in 1958, the 32-story, 127-meter-high Pirelli Tower, with its unique hexagonal plan, became Italy's first skyscraper and a symbol of the postwar economic recovery of Italy.

Two of his most renowned architectural works, though, were built outside of Italy. One of these works is Villa Planchart, or “El Cerrito” (1955), in Caracas, built for Anala and Armando Planchart at the top of a hill, or cerro, overlooking Caracas. For the Villa Planchart project, Ponti designed the 10,000-square-foot, six-bedroom house, and the furniture and decorative objects. Another of Ponti's most famous works is Villa Nemazee (1957–1964) in Tehran. The Namazee family commissioned this home at the recommendation of Mohsen Foroughi, architect and dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts at Tehran University. For Villa Namezee, Ponti developed a design based on the traditional Iranian courtyard house. The Iranian regime has since revoked the villa's heritage status, making its future uncertain. Italian artist and ceramicist Fausto Melotti collaborated on the interior design and furnishings of both villas.

In the 1970s towards the end of his career, Ponti was on an intense mission to explore transparency and lightness in his work. During this time, he designed and built facades resembling undulated and perforated sheets of paper with geometric shapes and unique patterns. In 1970, he finished the Taranto Cathedral, a white rectangular building with a huge concrete façade punctured with openings. In 1971, he contributed to the exterior envelope design of the Denver Art Museum in Colorado—the only Gio Ponti building in North America. He also submitted the project design for the future Centre Pompidou in Paris.

In 1934, he was given the title of Commander of the Royal Order of Vasa in Stockholm. He also obtained the Accademia d'Italia Art Prize for his artistic merits, the gold medal from the Académie d'Architecture in Paris, and an honorary doctorate from the London Royal College of Art.

Gio Ponti died in 1979 on Via Nezza in Milan. His many prizes and titles throughout his life signify his importance as a designer. His furniture and design objects continue to be sought after by collectors today, indicating the revolutionary status of his mid-century designs.