Side Gallery

Side Gallery

WishlistFollow

Follow

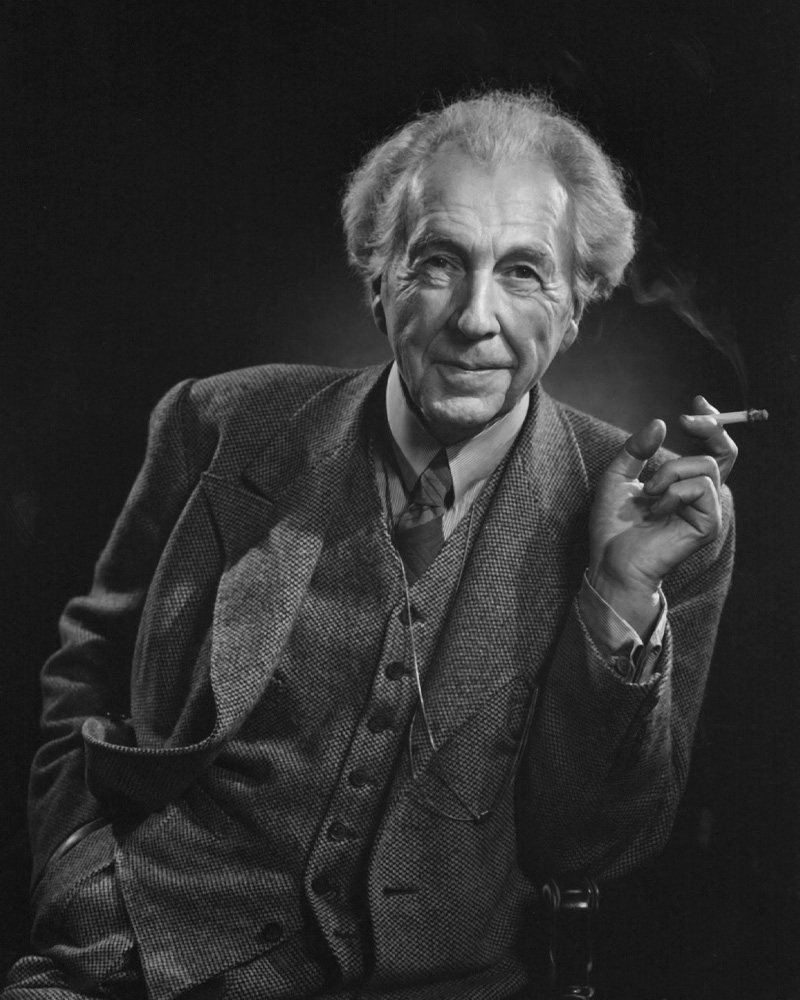

Frank Lloyd Wright liked to say he was an American original, but in truth, his imagination was fed by many places, many objects, many worlds. Born in 1867 in rural Wisconsin, he grew up among open fields and small wooden houses. His mother filled his childhood with Froebel blocks — little wooden cubes and cylinders that could be stacked into endless patterns. Wright never forgot them. Those simple toys became the seeds of his architecture, the grammar of shapes and rhythms that would mark every house, every piece of furniture, every building he created.

By the time he arrived in Chicago in the late 1880s, the city was reinventing itself after the Great Fire, and Wright was swept into its energy. He worked under Louis Sullivan, the prophet of “form follows function,” and learned to think of buildings as living organisms. But Wright had a restless confidence. Soon enough, he left Sullivan’s firm and set out on his own, determined to build not just houses but a new way of life.

Wright’s early commissions in Oak Park and the Midwest became the famous Prairie houses. They were long and low, roofs stretched wide, with interiors that flowed into one another. They didn’t sit on the landscape; they seemed to grow from it.

But for Wright, the walls and roofs were only the beginning. He believed in the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk — the total work of art. If he designed a house, he would design everything inside it too. Chairs, tables, light fixtures, rugs, even stained glass patterns — all had to belong.

His furniture was radical for its time. High-backed dining chairs turned the dining table into a kind of sacred chamber, shielding sitters from distraction. Built-in benches extended from walls, merging furniture with architecture. Armchairs and desks echoed the same sharp geometry as the windows and beams above them. Critics sometimes called his pieces stiff, even uncomfortable, but Wright saw them as instruments of order. The furniture disciplined the body, just as the house disciplined the spirit.

In 1905, restless again, Wright boarded a ship and sailed to Japan. He had long admired Japanese prints, with their bold outlines and flat planes, and in Tokyo and Kyoto he discovered the architecture that matched them: simple wooden houses, sliding screens, spaces open to gardens and air. It was a revelation. Japanese buildings, he realized, were not solid objects but delicate frames for light and life. They seemed to dissolve the boundary between inside and outside. Wright was entranced.

He began collecting ukiyo-e woodblock prints, not only for pleasure but also to finance his life and practice back home. These prints sharpened his eye for geometry and space, for the poetry of horizontal lines and the silence of empty planes. When he returned to America, his work carried a new quietness, a Japanese clarity wrapped around American ambition.

That fascination turned into reality when, in 1915, Wright was commissioned to design the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. It was to be a grand, modern symbol of Japan’s place in the new century. Wright threw himself into the project. He studied Japanese carpentry, admired the precision of joinery, and blended it with his own love for Mayan stonework and Prairie horizontality.

The hotel, completed in 1923, was unlike anything else in the world: part modern palace, part temple, part machine. Inside, Wright designed everything — lamps, carpets, and especially furniture. The armchairs and tables for the hotel were massive yet refined, with angular profiles and richly upholstered surfaces. They were made to last, and to belong only to that building.

On the very day of its opening, disaster struck: the Great Kantō Earthquake shook Tokyo. Buildings toppled and fires raged, but the Imperial Hotel stood. Word spread quickly: Wright’s building had survived. Though later demolished, the hotel became a legend, proof that architecture could be both beautiful and resilient.

Wright never stopped designing furniture. Each phase of his career brought new experiments.

In the Prairie years, his furniture was tall, rectilinear, meant to enclose space as much as to serve it.

In the Imperial Hotel, the chairs and tables showed his ability to merge Western comfort with Japanese sensibility, sturdy yet graceful.

In his Usonian houses of the 1930s and beyond — simple homes for middle-class families — his furniture became more modest, often built-in, designed to be affordable, modular, and democratic.

To Wright, furniture wasn’t decoration. It was the human scale of architecture, the part you touched, the part you lived with. A house without its own furniture was unfinished, like a poem without its last line.

Even in his 80s, Wright was still pushing forward. He dreamed up mile-high skyscrapers, desert compounds, and futuristic cities. In New York, he designed the Guggenheim Museum, a spiraling shell that turned art-viewing into a continuous flow of movement.

When he died in 1959, just before the Guggenheim’s completion, he left behind more than buildings. He left a philosophy: that design must embrace every detail, from the sweep of a roof to the curve of a chair; that architecture is not about walls but about the way people live within them.

His years in Japan gave him serenity, a love of lightness, and a deeper understanding of how nature and architecture could intertwine. His furniture — angular, disciplined, sometimes controversial — revealed his belief that harmony mattered more than comfort, and that objects were part of the same grand composition as the buildings themselves.

Frank Lloyd Wright saw the world as a great, unfinished design. And in every house, every hotel, every chair, he tried to shape a piece of it into harmony.

ENQUIRE ABOUT THE DESIGNER