Side Gallery

Side Gallery

WishlistFollow

Follow

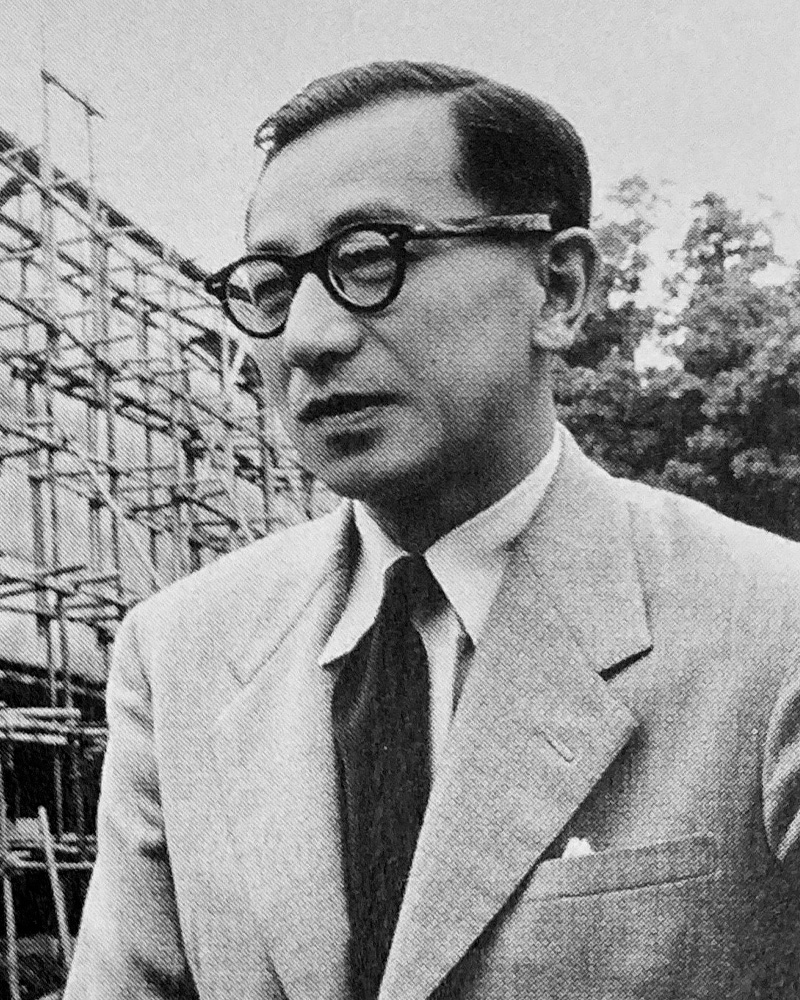

Junzō Sakakura was born in 1901, in the small rural world of Gifu Prefecture, Japan. His early life was rooted in simplicity — tatami floors, wooden structures, the everyday intimacy of Japanese homes. That sensibility never left him, even as he grew into one of the great voices of modern architecture.

At first, he studied art history at Tokyo Imperial University, fascinated not so much by the structures themselves as by the stories and aesthetics behind them. But the pull of design was too strong. In 1929, he made the bold move to Paris, where fate — and a few connections — carried him to the atelier of Le Corbusier. In Paris, Sakakura entered a world of rigorous geometry, reinforced concrete, and radical visions for the future. He worked his way up in the studio until he became Le Corbusier’s chief assistant. The experience changed him profoundly. Here was a Japanese man, steeped in the traditions of wood and tatami, immersed in the epicenter of European modernism. He didn’t abandon one for the other; instead, he began to imagine how both could coexist.

His breakthrough came in 1937, when he was asked to design the Japanese Pavilion for the Paris International Exposition. The result was striking: a clean, modern structure lifted above the ground, filled with light, circulation, and rational form — yet quietly carrying the harmony and restraint of Japanese tradition. It won the exposition’s Grand Prix and marked Sakakura as a bridge between worlds. After the war, Japan was in ruins, and Sakakura returned home determined to help rebuild. He opened his own office and quickly became known for public works that combined functionality with elegance. One of his most beloved projects was the Museum of Modern Art in Kamakura (1951), a serene place where modernist concrete frames blend with surrounding gardens and ponds.

He collaborated with fellow Japanese modernists like Kunio Maekawa and Junzō Yoshimura on the International House of Japan in Tokyo, and he was entrusted with executing Le Corbusier’s design for the National Museum of Western Art (1959). He also shaped the public life of a rapidly urbanizing Tokyo with station plazas, department stores, and civic halls. Through it all, Sakakura held fast to a principle: design should serve people. Buildings, yes — but also the smaller things, the objects that people touched every day.

Sakakura never separated architecture from interiors. To him, a room was incomplete without furniture that fit its proportions, materials, and spirit. This belief led him to design a range of chairs and tables, often in collaboration with Tendō Mokko, a Japanese manufacturer specializing in molded plywood. One of his earliest forays into furniture came in 1950, when he entered the Museum of Modern Art’s international competition for low-cost furniture in New York. His “Bamboo Chair” won an honorable mention. The design was clever and economical — a simple seat born of modest materials — reflecting both the resourcefulness of postwar Japan and his own drive to create for everyday life.

He continued refining his ideas through the 1950s and 60s. Among his most admired works is the Lounge Chair, Model 5016 (1957), produced by Tendō Mokko. With its gently curved plywood frame, upholstered seat, and low, inviting stance, the chair balances comfort with understated elegance. It became a quiet classic of Japanese modern furniture.

Sakakura also designed the Teiza Chair, unveiled at the 1960 Milan Triennale. Low to the ground, with a sled-style base and molded plywood frame, it translated traditional Japanese floor-sitting customs into a modern form. This was Sakakura at his most insightful — merging cultural heritage with global modernism.

Other pieces, such as the 3222 side chair from the mid-1950s, show his focus on functionality, clean lines, and materials that could be adapted for mass production in a recovering economy. Each design carried the same philosophy: simplicity, human comfort, and a quiet dialogue between past and future.

Sakakura’s life was not only about monumental buildings or iconic pavilions. It was about balance — between East and West, tradition and modernity, architecture and furniture. He saw no hierarchy between a museum and a chair; both shaped human experience, both deserved thought and care. He died in Tokyo in 1969, but his legacy continues to ripple through Japanese design. His buildings remain landmarks of postwar modernism, and his furniture has gained new appreciation among collectors and design enthusiasts worldwide. When you sit in one of his chairs — low, simple, comfortable — you can feel the same principles that guided his architecture: clarity, restraint, and a deep respect for human life. Sakakura believed design should make living better, whether through the walls of a museum or the curve of a seat. In that belief, he built not just structures, but a philosophy that still resonates today.

ENQUIRE ABOUT THE DESIGNER