Side Gallery

Side Gallery

WishlistFollow

Follow

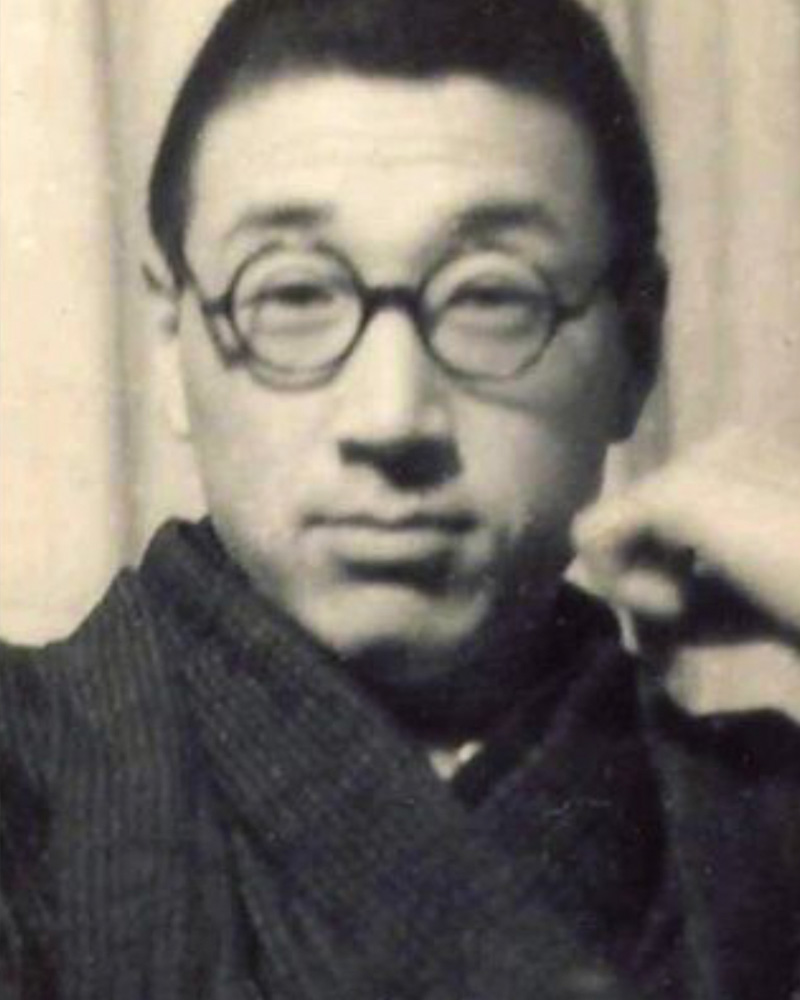

Ubunji Kidokoro 城所右文次 (c. 1910–1945) was a Japanese cabinetmaker and furniture designer whose brief but influential career in the 1930s helped articulate a distinct Japanese response to international modernism by marrying indigenous materials and craft practices with the formal and structural experiments of the period. Little is recorded about his childhood and formal schooling, but by the mid-1930s Kidokoro was working as a designer and cabinetmaker associated with Mitsukoshi, Japan’s oldest department store, where a progressive furniture office sought to introduce “modern” seating and furniture for a society that had for centuries largely sat on tatami; it was in this environment that Kidokoro’s best-known work took shape.

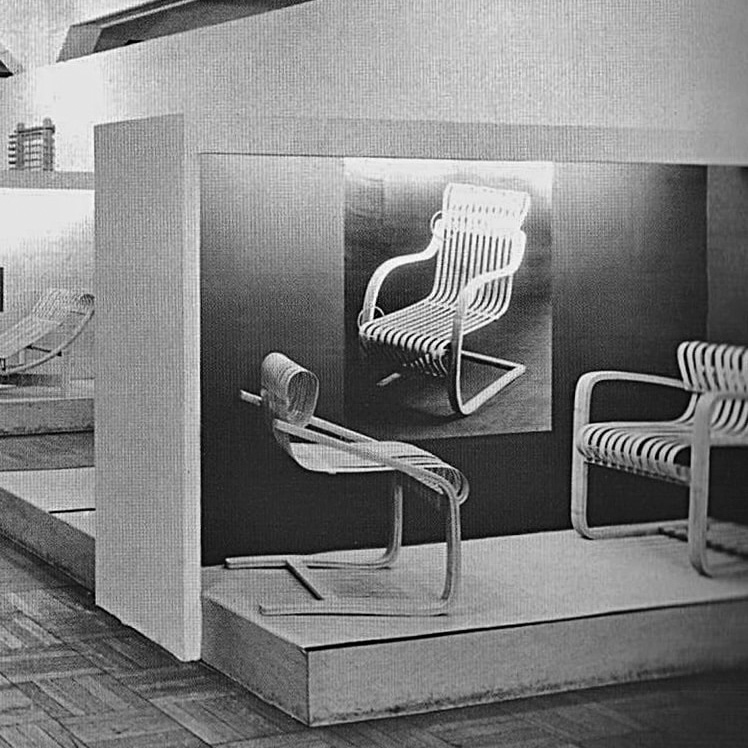

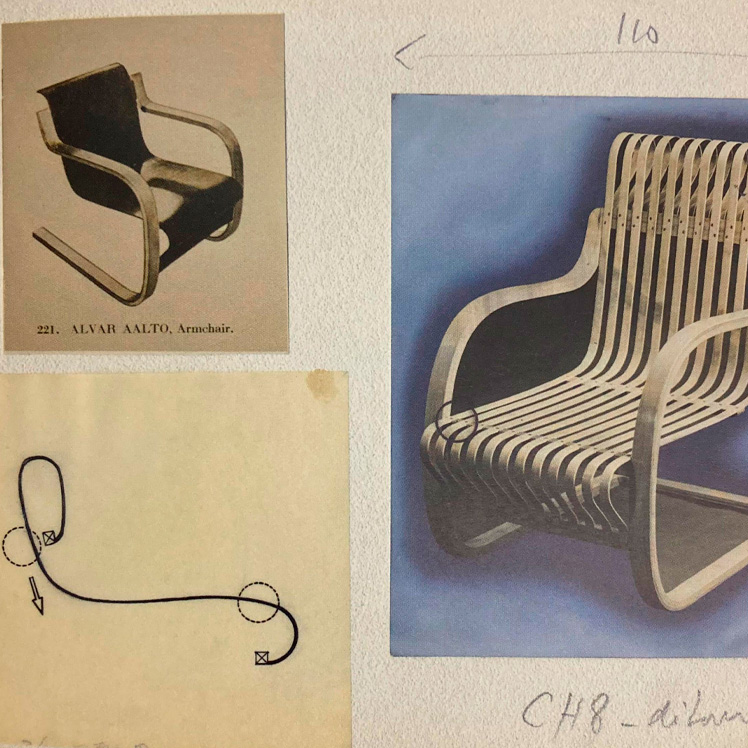

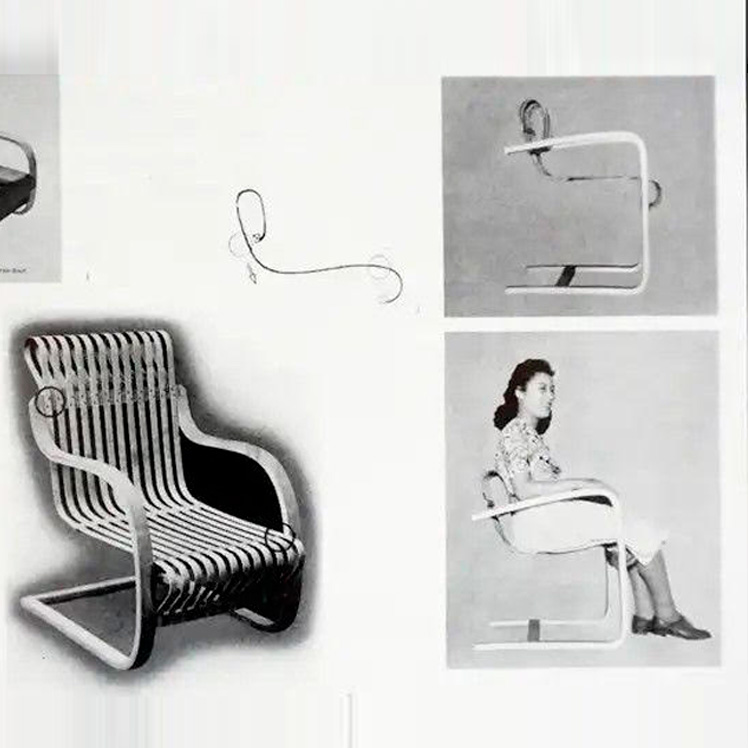

Around 1937 Kidokoro produced his iconic cantilevered bamboo armchair for Mitsukoshi, a design that became emblematic of the store’s modern furnishing program. The chair is constructed from layered bent plywood and long vertical strips of bamboo fastened with brass studs; its arms extend into a continuous curving base and the seat slightly cantilevers so that the piece yields subtly to the sitter’s weight. This solution exploited the spring and tensile qualities of bamboo and of laminated ply, creating a lightweight yet resilient structure that read as both modern and unmistakably Japanese in material sensibility. The piece was widely exhibited and later entered important museum collections.

Kidokoro’s work is often discussed in relation to contemporaneous Western experiments with bentwood and cantilever structures, most notably the work of Alvar Aalto; Kidokoro’s 1937 bamboo armchair can be seen as a Japanese interpretation of that structural idea, but made manifest through local materials and craft processes rather than mere imitation. His approach was not to copy Western forms, but to translate the underlying structural logic into a register that drew on mingei (folk-craft) values — an emphasis on local raw materials, skilled handwork, and modest, utilitarian beauty — producing furniture that felt both international and regionally rooted.

Archival evidence and auction records show that Kidokoro’s pieces were manufactured by specialist workshops such as Chikukousha under commission from Mitsukoshi; these makers developed the layered bamboo ply and lamella bending techniques needed to realize Kidokoro’s ambitious curves. Surviving examples of his work — appearing at auction houses, dealers, and in museum acquisition catalogues — often retain factory labels or maker notations that tie them to these producers, confirming a small but significant industry in Japan at the time capable of advanced plywood and bamboo laminating techniques.

Kidokoro’s designs were shown beyond Japan, participating in the international flows of design and exhibition that characterized the 1930s. Contemporary accounts and later curatorial notes indicate that modest Japanese modern furniture, including works like Kidokoro’s, traveled with department store exhibitions and international shows that attempted to present a renewed, modern domestic aesthetic. Some sources note that works linked to Mitsukoshi and to designers such as Kidokoro were seen in exhibitions and fairs that introduced Japanese modern furniture to foreign audiences in the late 1930s. This had the double effect of placing Kidokoro’s work in a global conversation about modern living while also complicating authorship and influence when European designers such as Charlotte Perriand and others engaged with Japanese bamboo seating during their own visits and exhibitions.

Tragically, Kidokoro’s career and life were cut short by the Second World War; museum object records commonly list his dates as approximately 1910–1945, and several reference works assert that he died in 1945, a loss that prevented him from developing a larger oeuvre or from participating in the rich postwar revival of Japanese design. The scarcity of personal archives, few surviving production records, and the wartime destruction that affected many Japanese makers have all contributed to the fragmentary nature of Kidokoro’s documented biography.

Despite the brevity of his output, Kidokoro’s surviving pieces have had a long and varied afterlife: they appear in major museum collections (for example the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne and the Brooklyn Museum in New York), in design-museum retrospectives, and on the international market where specialist dealers and auction houses periodically offer original examples dating from the late 1930s. These institutions and sales catalogues provide technical descriptions (materials, dimensions, makers’ marks) that have been essential for reconstructing his methods: layered bamboo plywood bonded into lamella bends, vertical bamboo slats secured to crosspieces with brass studs, and the deliberate use of cantilevering to create a responsive seat.

Stylistically, Kidokoro stands at an important crossroads in Japanese design history: he demonstrates how local craftspeople absorbed and reformulated modernist formal ideas while preserving the primacy of indigenous materials and making techniques. His chairs are warm, tactile, and deceptively complex — they demand a high level of joinery and lamination skill and reveal an aesthetic that privileges structural honesty and the visible logic of construction. Because his surviving works are both technically interesting and visually compelling, scholars and curators often use Kidokoro as a case study when discussing prewar Japanese furniture that anticipated the postwar global interest in Japanese modern design.

From a practical, object-level standpoint, the condition reports and auction notes for Kidokoro’s chairs teach us about the material vulnerabilities of bamboo ply: hairline cracks at edges, separation at seams, varnish crazing and loss — all aging characteristics that require sensitive conservation. Such technical details underline the care required to preserve this type of furniture and also explain why original pieces are relatively rare on the market and prized by collectors. Major sales and catalogues (Sotheby’s, specialist dealers, and curated showrooms) provide photographic records and provenance notes that have helped re-introduce Kidokoro’s name to contemporary collectors and museums.

Today, Ubunji Kidokoro is remembered less as a prolific designer than as a seminal figure whose inventive use of bamboo and plywood in the late 1930s opened a dialog between craft and modernity in Japan. His surviving chairs function as physical testimonies to an era when Japanese designers and department stores experimented boldly with new domestic forms, and they continue to be studied, conserved, exhibited, and occasionally sold, ensuring that Kidokoro’s experimental fusion of material, craft, and modern structural thinking remains part of the broader story of twentieth-century design.

ENQUIRE ABOUT THE DESIGNER