Side Gallery

Side Gallery

WishlistFollow

Follow

Born in 1912 in Tokyo, Japan, Isamu Kenmochi 剣持勇 was one of Japan's leading interior and product designers, and one of the pioneers who laid the foundations for the design trend known as Japanese Modern. From the chaotic postwar period through the years of rapid economic growth, Kenmochi was deeply involved in Japan's industrial design and the development of living environments. He expanded his activities beyond furniture design to include exhibition design, showroom production, and even the creation of educational systems for design, pursuing a “comprehensive design” aimed at improving the quality of living spaces as a whole.

After graduating from the Woodcraft Department of Tokyo Higher Technical School in 1932, Kenmochi joined the Ministry of Commerce and Industry's Crafts Guidance Center. The following year, he engaged in research on “normative archetypes” for chairs under the tutelage of German architect Bruno Taut, who was then visiting Japan. It is believed that his fundamental ideas about materials, structure, and form were largely cultivated during this period.

After the war, he was involved in designing and directing the mass production of furniture for the housing of occupying forces, creating over 30 pieces of furniture in a short period of time and making a significant contribution to establishing quality standards for mass-produced furniture in Japan. This was not only a practical project during the reconstruction period, but also the starting point for Kenmochi’s pursuit of reconciling industrialization and handcraft.

In 1950, he collaborated with sculptor Isamu Noguchi and architect Kenzo Tange, who were visiting Japan, to create a chair made of bamboo, challenging himself to combine materials, form, and structure. Through this experience, Kenmochi began to seriously consider how to incorporate Japan’s unique materials and culture into modern life. In 1952, he helped establish the Japan Industrial Designers Association (JIDA), alongside Watanabe Riki and Yanagi Sori, promoting the institutionalization and professionalization of industrial design in Japan. In 1955, he founded the Kenmochi Design Institute and began working on a wide range of projects, from furniture to spatial design, all based on a consistent vision.

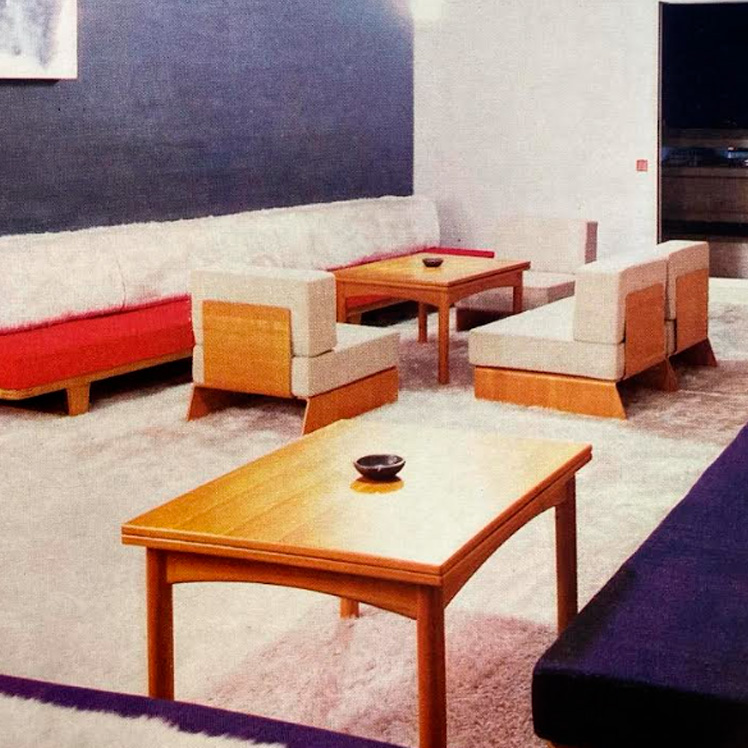

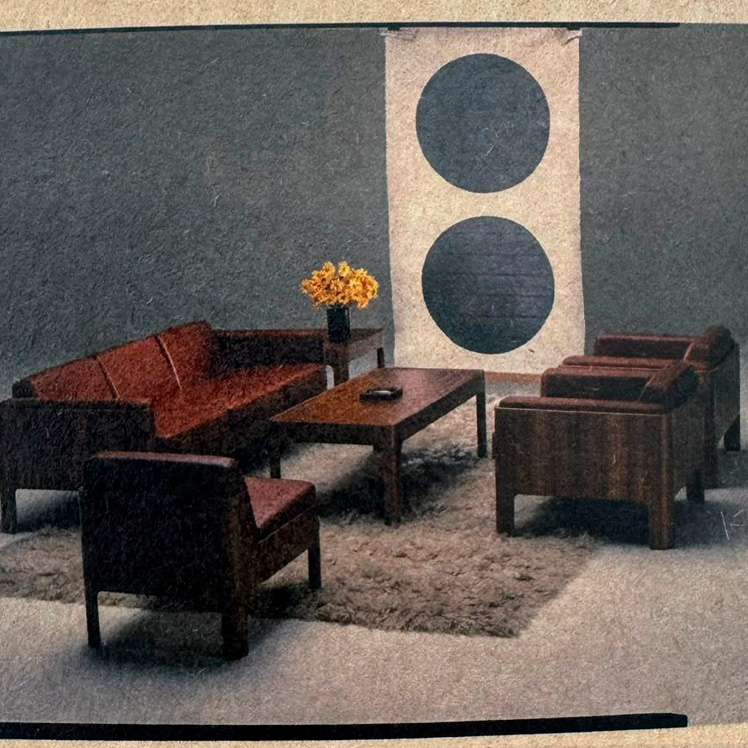

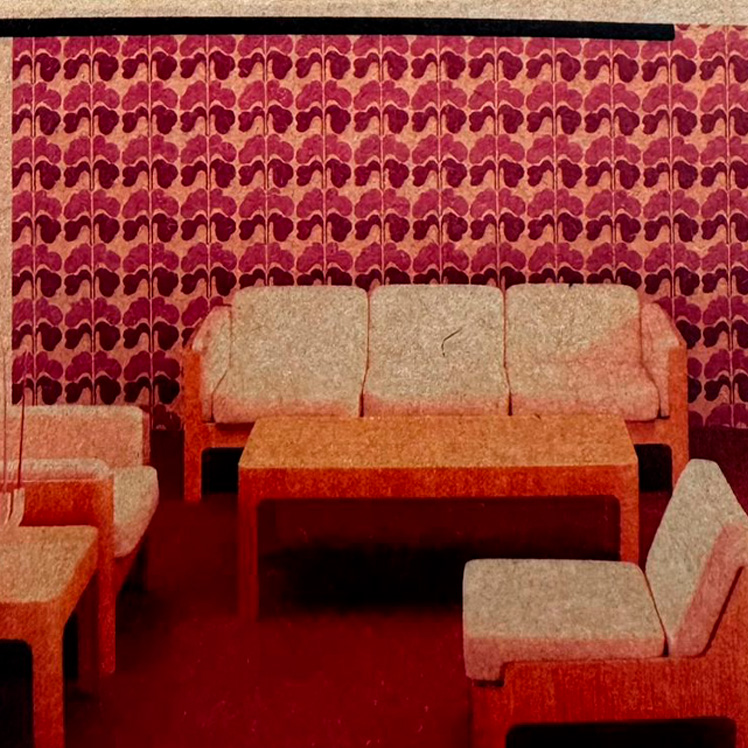

Kenmochi’s designs emphasized not just aesthetic beauty but harmony with the user’s body, habits, and space, and he viewed furniture as one of the elements that make up a “place.” In his showrooms of the 1950s, he presented numerous pieces under the concept of Japanese Modern (or Japonica), utilizing traditional Japanese materials such as bamboo, washi paper, lacquer, and rattan.

Kenmochi was also active internationally, representing Japan at events such as the Aspen Conference and the World Design Congress. Through dialogue with Charles and Ray Eames and Isamu Noguchi, he promoted the significance of Japanese design in the international community. He had a particularly close relationship with the Eameses, once remarking: “Their work exudes their unpretentious personalities.”

One of his signature works, the Rattan Chair (1958), combines a modern form with comfortable seating, utilizing rattan, a traditional Japanese material. In 1964, it was selected for the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. He also undertook numerous other projects that shaped the landscape of postwar Japan, including furniture for Hotel Okura’s guest rooms, the interiors of Haneda Airport’s VIP lounges, exhibition spaces for international trade fairs, and signage plans for public facilities.

Underlying his work was a deep understanding of Japan’s climate and materials, and a constant inquiry into how to embed them into modern life. His designs were both functional and poetic, Japanese yet international. Even today, Kenmochi’s ideas and practices continue to influence designers worldwide, and his significance as a central figure in shaping Japanese modernism is being reevaluated.

ISAMU KENMOCHI AND TENDO MOKKO

Isamu Kenmochi was a man who introduced the concept of design to Japan throughout the prewar and postwar periods, working to raise awareness of its role and improve people's lives. In 1932, he became an engineer at the National Crafts Training Institute of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry (now the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry). In 1933, architect Bruno Taut was appointed to the institute on a contract basis, and Kenmochi studied under him, researching the “standard prototype of chairs.”

In 1952, he became the first Japanese designer to visit the United States, where he was deeply influenced by his encounter with Charles and Ray Eames. This visit forced Kenmochi to confront the issue of establishing and communicating the originality of design in his own country, and he came to develop the concept of Japanese Modern. The same year he returned to Japan, he was involved in the founding of the Japan Industrial Designers Association, with the aim of establishing and improving the industrial design profession. In 1955, he also helped launch the Japan Design Committee, which aimed to promote good design. That same year, he went independent.

Kenmochi’s relationship with Tendo Mokko began during the wartime National Crafts Training Institute. While providing instruction in both design and technique for furniture production using molded plywood, he also collaborated with architects to design a variety of products, creating many of Japan’s most famous postwar interiors. His diverse work spanned a wide range of fields, including the Yakult lactic acid bacteria drink, a design beloved worldwide to this day.

From the public sector to the private sector, spanning the prewar and postwar periods, Kenmochi supported Japanese design from its early days and contributed greatly to its global reach. In June 1971, he oversaw the design of Japan’s first high-rise hotel, the Keio Plaza Hotel, and elevated Japanese Modern to a new level. However, Kenmochi’s overwhelming workload led to depression, and he died by suicide on the day of the opening party.

The Kenmochi Isamu Design Institute subsequently changed its name to the Kenmochi Design Institute, where it has continued to support Japanese design for half a century.

A design that cannot be imitated

“I thought there was a guy who looked pretentious, and it was Kenmochi. He was the type I didn’t like,” says Matsumoto Tetsuo, director of the Kenmochi Design Institute, laughing as he recalls meeting Kenmochi. After Kenmochi passed away, Matsumoto took over the firm, and the Kenmochi Design Institute has continued to produce many masterpieces ever since. In addition to furniture and interiors, they also produced street furniture that can still be seen in various places today, the interior and exterior decoration of different train carriages including the Shinkansen, and the yellow handy mop from Duskin. They have produced a wide range of products and spaces.

Kenmochi and Matsumoto’s encounter dates back to the days of the Industrial and Crafts Research Institute. Matsumoto, who graduated as one of the first students from the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, Chiba University, joined the Industrial and Crafts Research Institute in 1953. This was the year after the Ministry of Commerce and Industry’s National Crafts Guidance Institute, established in 1928, was reorganized as the Industrial and Crafts Research Institute under the Ministry of International Trade and Industry. Matsumoto, worried about finding a job, visited the institute on the recommendation of his mentor. The written exam was held that day, followed by an interview that afternoon, where he was hired. Kenmochi, who was head of the institute’s design department at the time, was looking for someone with an architecture degree, and Matsumoto recalls with a wry smile that the groundwork had been laid in advance.

Kenmochi met Eames and George Nelson during a visit to the United States in 1952, and Matsumoto continues: “He said that when he saw designers working independently in the United States, he became convinced that the same era would surely come to Japan. And because all the people designing interiors in the United States had studied architecture, he wanted people who had studied architecture.”

When Matsumoto joined the institute, Kenmochi was away at the Aspen International Design Conference in Aspen, Colorado, USA (held from June 23rd to July 1st, 1956, at which it was decided that the World Design Conference would be held in Japan in 1960. That conference is known for inspiring the Metabolism movement in architecture and for having a major influence on students such as Miyake Issey and Ishioka Eiko, who were students at the time). When Matsumoto saw Kenmochi upon his return to Japan, he had the same impression as mentioned above.

“A white shirt with a bow tie was something that didn’t exist in Japan at the time. Later, Kenmochi told me that Eames and Nelson also wore bow ties, which were convenient because they didn’t hang down when they were drawing, and that made sense. In an era before air conditioning, Kenmochi wore suits even in the summer. His father had served as an army major, so he must have been strict in his upbringing. When handing out summer bonuses, he would do so wearing a jacket and tie, but it was so hot for us staff members that we were dressed in shorts and running shirts. Kenmochi would get mad at us for not doing things properly at milestones, so one of the staff members would take turns wearing a jacket kept in the office to go and collect it. So Kenmochi must have been a bit eccentric.

When we received royalties for our articles in magazines and newspapers, he would often take the whole staff out to the movies. Since he was paying for everyone, our income was actually in the red. Sometimes Kenmochi would get scolded by the accounting department afterwards.”

Kenmochi left the Industrial and Crafts Research Institute in June 1955 and opened his own office. He then dismissed Matsumoto, who was in his second year at the institute, saying: “I’m not getting paid. I’ll call you when you’re ready to do it, so until then, just help out at night.” After finishing his work at the institute, Matsumoto began to commute to Kenmochi’s office. “I remember thinking it was cool back then when they called me the night chief, but I was always working until the last train,” he recalls.

Matsumoto then left the Industrial and Crafts Research Institute after four years there and began to demonstrate his skills as chief designer under Kenmochi.

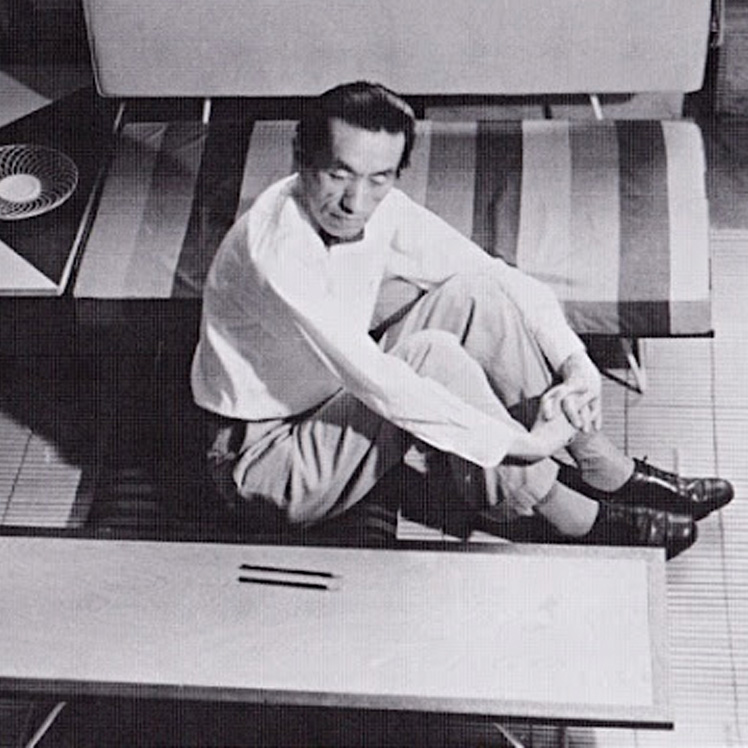

“Kenmochi originally studied woodworking. He was head of the woodworking section at the Industrial Crafts Testing Institute before becoming head of the design department. He knew a lot about wood processing, and I had no choice but to study it myself. How can you draw blueprints if you don’t know how to make something? In short, he was very skilled at drawing. When I first met him, he was standing and drawing full-scale drawings freehand. He would even quickly sketch them during a meeting. He was someone you couldn’t compete with if you made suggestions based solely on intuition.”

When Kenmochi first traveled to the United States, it was difficult to cover everything with government funds. He sold his Nikon camera there to supplement his travel expenses and instead purchased a cheaper one. After returning to Japan, Kenmochi had to travel around the country to give reports to instructors, and color slides were essential.

“It was his first time going to the US, and he had no money, so he traveled on a passenger/cargo ship. He entered the US from Guam by ship, passed through Hawaii, and arrived in San Francisco on the West Coast, where he stayed at the Eames House in Los Angeles. He had been exchanging letters with the Eames and others. This time, he traveled across the continent by coach to meet George Nelson on the East Coast. He stopped off at Frank Lloyd Wright’s place along the way, visiting the East on the way there and the West on the way back.

Information wasn’t as readily available back then, and Kenmochi’s English was broken, but he still managed to cross the US alone. It was strange, even though he wasn’t intimidated. He extended his stay, saying he still had more to learn. Then, after returning home, he generously shared the knowledge he had gained, showing people what was happening in the US. At the time, it was rare to see Eames furniture in person. So I’m sure everyone was amazed when he showed them that molded plywood chair. And that’s when the term Japanese Modern came up.”

“Matsumoto continues: ‘Kenmochi didn’t come up with the term Japanese Modern. His stay in the US coincided with the rise of Scandinavian furniture, as Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland strategically began selling furniture, tableware, and textiles. The buyer explained to me that in America, even the average customer has a certain style that comes to mind when they think of Swedish Modern. So the idea was that Japanese furniture would also have to develop a market with a style people would associate with Japanese Modern.

In other words, Kenmochi reported that Japanese furniture needed distinctive features to make an impact on the world market, but at the time some people were annoyed, saying that Kenmochi had come back all American. He was wearing a bow tie, for example. They mocked him, saying that he had only a Japanese taste.’”

Matsumoto believes that Kenmochi’s early visit to the United States had a profound impact on the entire furniture industry. By sharing his encounters with various designers and stories with the industry, he aimed to raise the morale of Japanese design. Kenmochi articulated and advocated the concept of Japanese Modern. Its merits and demerits eventually escalated into a debate still rare in the Japanese design world, resulting in the opening essay (page 32) of this book. Its essence lay in the pursuit of high-quality, original design that combined modern Japanese lifestyles with industry, handicrafts, and crafts.

Matsumoto also describes Kenmochi’s own designs as truly inimitable. The rattan lounge chair (now manufactured and sold by YMK Nagaoka) from Yamakawa Rattan features a seat made of woven wood, while Tendo Mokko’s Kashiwado chair features a seat carved out of stacked wood. Both chairs are simple in concept yet richly unique. Matsumoto recalls that both pieces of furniture began as Kenmochi’s sketches.

“On the other hand, Kenmochi would often ask me to come up with ideas. When I handed him a sketch, he would make corrections. I would then respond and rewrite the drawings. This exchange continued, and we got closer to completion. Of course, Kenmochi Isamu was the sole name in the public eye, so I didn’t use my name. So when I took over, we decided that the design was done by the Kenmochi Design Institute. If Kenmochi’s designs have a wide range, I think it’s because they were born from a simple desire to do something, to make something, and then they took shape.”

A respected senior, Isamu Kenmochi

Imazaki Taku, who joined the Industrial and Crafts Research Institute in 1955, was a student at the Tokyo University of the Arts at the time.

“I used to go to see Kenmochi-sensei’s lectures at the Kogei Shidosho. The lectures were about German modern design and Bauhaus. He talked about works by Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, but also about Bruno Taut’s stay in Japan, which I found very interesting. Later, I went to work at the Kogei Shidosho, and Kenmochi-sensei was still there, so I was very happy.”

Imazaki recalls:

“Kenmochi-sensei was really stylish. He was strict about manners and appearances. Even when it was hot, he wore a jacket and tie, never casual clothes. He never looked sloppy. He always kept his dignity.”

Shimizu City and Kenmochi

Kenmochi was also deeply connected to Shimizu City, Shizuoka Prefecture (now part of Shizuoka City). He was invited to be an advisor on local industry promotion and was involved in developing local crafts, including bamboo products and furniture. He also gave lectures and provided guidance to young local designers, leaving behind a strong influence in the region.

Shimizu was one of the first cities to embrace Kenmochi’s concept of Japanese Modern in daily life. His ability to integrate local traditional techniques with modern industrial design helped raise the standard of regional industries and connected them to the national market.

Final years and legacy

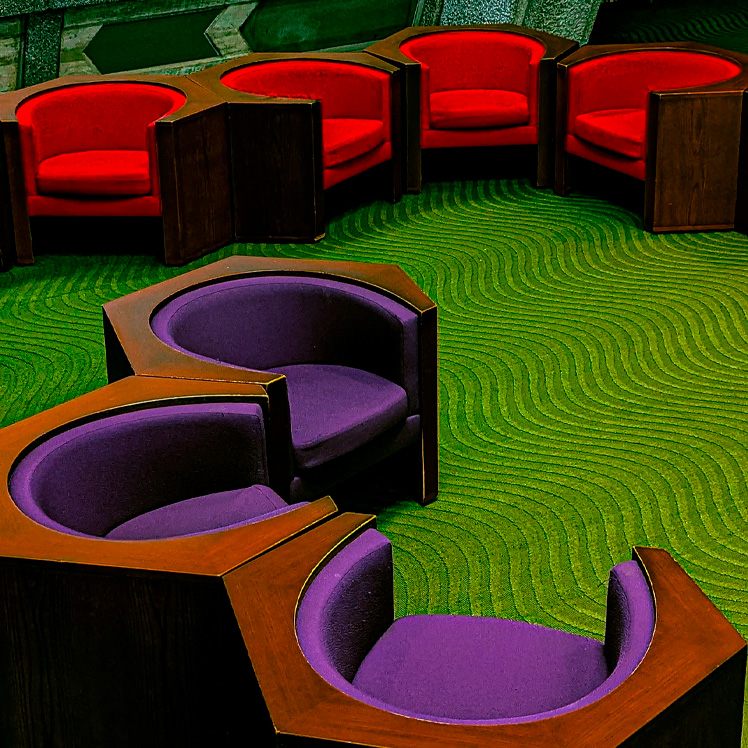

In June 1971, Kenmochi completed the design of the interiors for the Keio Plaza Hotel in Tokyo, Japan’s first high-rise hotel. This project symbolized the culmination of his vision of Japanese Modern, combining functionality, elegance, and modern technology while retaining Japanese identity.

However, the enormous workload, accumulated stress, and the pressures of being at the forefront of Japan’s design world took a heavy toll. On the day of the hotel’s opening party, Kenmochi died by suicide. He was 59 years old.

Despite his tragic end, Kenmochi’s legacy has never faded. His philosophy of merging modern industrial design with traditional Japanese culture, his commitment to raising the quality of everyday life, and his pioneering work in creating a profession for industrial designers in Japan continue to inspire new generations.

The Kenmochi Design Institute, renamed after his passing, carried forward his vision. Under the direction of Matsumoto Tetsuo and later successors, it continued to produce interiors, furniture, and products that reflected Kenmochi’s approach to design: functional, humane, and deeply rooted in Japanese culture.

Today, many of Kenmochi’s works are preserved in museum collections, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. His designs, such as the Rattan Chair, remain timeless examples of how Japanese sensibilities can be expressed in modern form.

Kenmochi Isamu’s life embodies both the challenges and possibilities of design in postwar Japan. By bridging tradition and modernity, craft and industry, local and global, he helped shape the foundation of Japanese modern design. His ideas, born out of dialogue with both Japanese heritage and international movements, continue to resonate, affirming his place as one of the central figures of twentieth-century design.

ENQUIRE ABOUT THE DESIGNER